On Oaths by Angelica

Posted on 9 September 2022; updated on 10 September 2022

This article is part of the newsletter column A Sense of History.

On Oaths

Oaths traverse J.R.R. Tolkien’s works: they determine actions, outcomes, and the fate of multiple characters. The Silmarillion is defined by the quintessential oath that Fëanor and his sons swear in the great square of Tirion to pursue any being in Arda who may take and withhold from them the Silmarils. There is also Finrod’s oath sworn in gratitude to Barahir during the Dagor Bragollach, which promised help to him and his kin should they need it and would ultimately lead to Finrod's death. Elendil also swore an oath upon arriving in Middle-earth (“Out of the Great Sea to Middle-earth I am come. In this place I abide, and my heirs, unto the ending of the world”1), repeated by Aragorn when he was crowned king. There is also the oath of allegiance sworn by the Men of the Mountains to Isildur, which they broke when they refused to join the Last Alliance: Isildur cursed them to remain without rest, haunting the caverns beneath the mountains until their oath was eventually fulfilled during the War of the Ring. Eorl, first king of Rohan and Cirion, twelfth Ruling Steward of Gondor, swore an oath of alliance between the two kingdoms and agreed that whenever help was necessary, they would aid each other. Why did Elves and Men bind themselves with these unbreakable pledges?

An oath can be defined as a conditional self-curse consisting of three elements: firstly, a declaration by which the oath taker asserts that he is telling the truth or he promises to take some action in the future. Secondly, superior powers are invoked as witnesses to mete out the punishment if the oath is false or broken. It is sworn by or on sacred objects and sometimes accompanied by a sacrifice—seldom human, more often an animal—or by pouring wine into the earth. Thirdly, a curse is specified that will fall on the takers if the oath is violated. If it is fulfilled, the gods will grant protection—a combination of curse and blessing.

Oaths were just as frequent in human societies as in Middle-earth since the earliest cultures. In predominantly oral societies with few recognized written laws and where interpersonal transactions were carried out on an individual basis not regulated by formal contracts, oaths were the most frequent means to validate the truth, guarantee actions and define punishments. They were pre-legal forms of contracts, reinforced by magic and—as it were—psychological pressure.

Sumerians and Egyptians swore by their lives and, in treaties between nations, gods were appealed to. Mithra, a Hellenistic god of Iranian origin, was viewed as the god of contracts, the guardian of oaths and truth. Indians swore oaths holding water from the holy River Ganges, symbol of the divine. The essential necessity to have some means that validated the truth of a statement was defined by the Romans with the word fides, meaning trust and believability. But fides went beyond the abstract concept of trust; it was also a word that was used to me oath and was also the name of a deity whose temple on the Capitoline Hill was next to the temple of Jupiter: the divine input on the truthfulness of claims was crucial.

In the Abrahamic religions, oaths were admitted but it was explicitly stated that they had to be taken with great care. In Judaism, vain oaths, where one attempted to do something impossible to accomplish, denied self-evident facts, or negated a religious precept, and false oaths, in which the name of God was used to swear falsely, were considered sacrilege. Early Christianity tried to elude them, and for Islam, since an oath was primarily a pledge to God, a false oath was considered a danger to the soul of the believer.

In Germanic societies, oaths played an essential role to reinforce the authority of the leaders of the war bands and maintain order in a fundamentally violent warrior culture. Lords and retainers were bound by an unbreakable bond of personal loyalty, usually reinforced by an oath of allegiance and cemented on the lord’s pledge to offer protection in exchange for the readiness of the retainers to fight for him and, if necessary, die protecting or avenging him. Spoils were exchanged and lords granted weapons and treasure in a ceremony with deep symbolic significance that went beyond the material. After the Germanic peoples converted to Christianity, the church did not come into conflict with this warrior ethos but added sanctity to the bond by an oath over relics: “By the Lord, before whom these relics are holy, I will be loyal and true to N, and love all that he loves and hate all that he hates…; on condition that he keep me as I shall deserve, and carry out all that was our agreement when I subjected myself to him and chose his favor.”2

Centuries later, a ritual highly reminiscent of this one became an integral part of the ceremony whereby a knight became a vassal to his lord promising him auxiluim (aid) and consilium (counsel), doing homage and swearing an oath of fealty over the Bible and relics. As shown in the Bayeux Tapestry, one of Harold Godwinson’s most damning actions, which justified William the Conqueror’s invasion of England, was taking the crown for himself after Edward the Confessor’s death, breaking the oath he had sworn over holy relics pledging to support William’s claim to the throne.

Oaths in The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings fit almost seamlessly into these models, showing the Professor’s undoubted familiarity with the main features of historical oaths. Eorl and Cirion’s oath reflects the pledge to aid and counsel imbued in the feudal bond. The terrible punishment that the Men of the Mountains receive as consequence of the breach of their oath of allegiance to Isildur adds magical elements to the fate that a retainer or a vassal would suffer if they betrayed their lord or failed to fulfill their obligations to follow him to war, fight, and die for him: they would become outcasts, expelled from society, defenseless, suffering lifelong infamy and reproach. When Finrod is saved at great cost by Barahir and his men in the Fen of Serech, he not only “swore an oath of abiding friendship and aid in every need to Barahir and all his kin” but he also “in token of his vow … gave Barahir his ring” which would become an heirloom of his house.3 Finrod behaves as a grateful lord must: swearing an oath that he would provide assistance regardless of the circumstances and also granting treasure: a jewel with the emblem of the House of Finarfin to cement this promise.

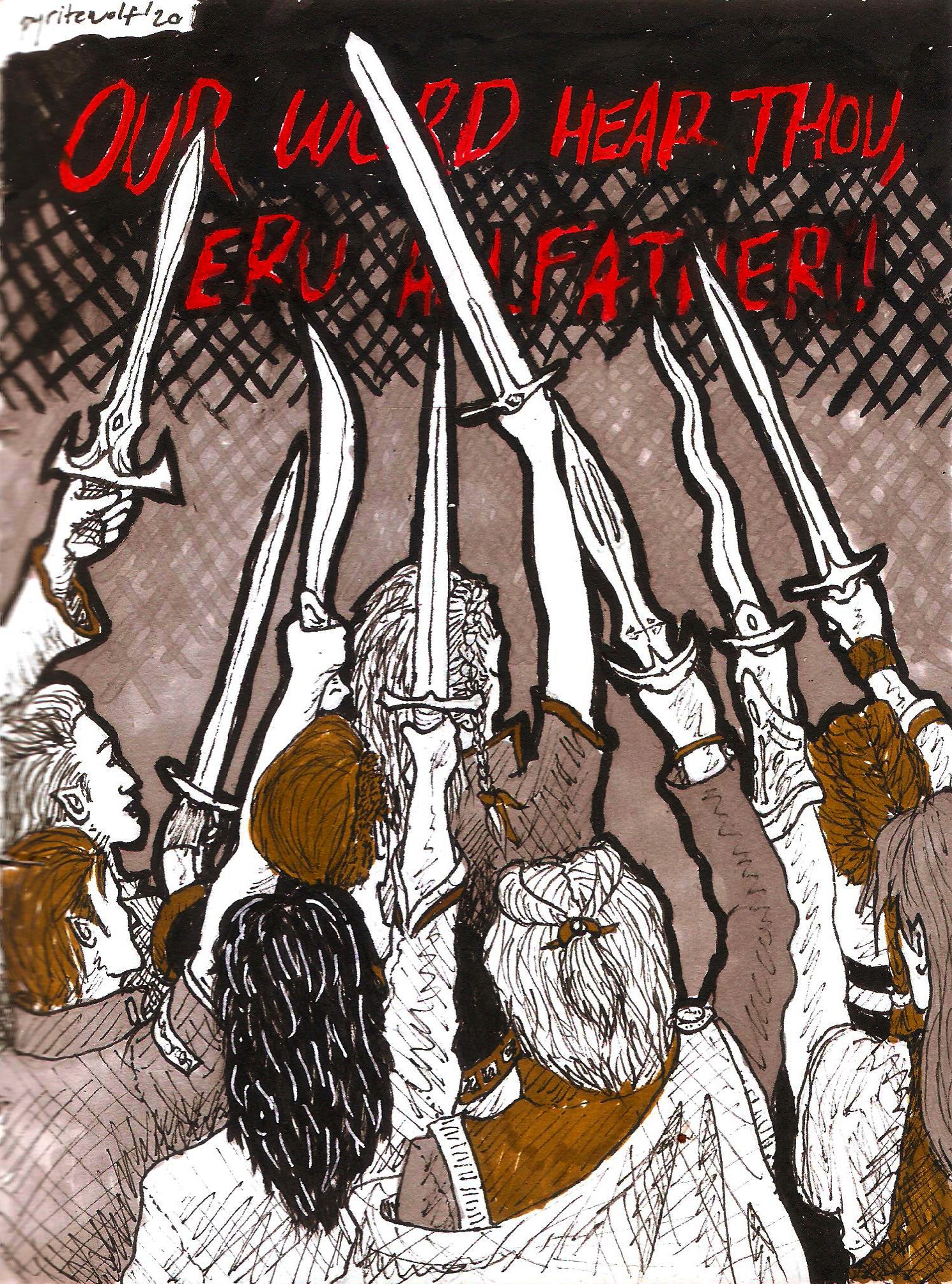

The Oath of Fëanor conforms to all the features that define oaths. No sacrifice is carried out but “red as blood shone their drawn swords in the glare of torches.” First, there is the promise to take action in the future: “Be he foe or friend, be he foul or clean, brood of Morgoth or bright Vala, Elda or Maia or Aftercomer, Man yet unborn, upon Middle-earth, neither law nor love, nor league of swords, dread nor danger, nor Doom itself shall defend him from Fëanor and Fëanor’s kin, whoso hideth or hoardeth or in hand taketh, finding keepeth or afar casteth a Silmaril”. Then the invocation to superior powers to witness: not just, “Our word hear thou, Eru Allfather” but also “On the holy mountain hear in witness and our vow remember, Manwë and Varda!” Finally, the punishment on the oath takers should they fail: “To the everlasting Darkness doom us if our deed faileth”.4 Self-curse, indeed.

Millennia later, at the time of the War of the Ring, the Elven attitude towards oaths has changed: when the Fellowship is about to leave Rivendell, Elrond and Gimli disagree on the need of an oath that would strengthen their resolution to carry out their mission. Elrond reminds the members that they go freely, and only Frodo bears a burden he cannot set aside—namely to carry the Ring to Mount Doom—while on the others “no oath or bond is laid”. Gimli disagrees and argues that a "sworn word may strengthen quaking heart”. But Elrond rejects this since an oath would not contribute but might indeed break the resolve of the participants: “let him not vow to walk in the dark, who has not seen the nightfall.”5

Works Cited

- The Lord of the Rings: Return of the King, "The Steward and the King."

- Dorothy Whitelock, The Beginnings of English Society (London: Penguin, 1959), 33.

- The Silmarillion, “Of the Ruin of Beleriand and the Fall of Fingolfin.”The History of Middle-earth Volume X: Morgoth’s Ring, The Annals of Aman, "Of the Speech of Fëanor upon Túna," §134.The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, “The Ring Goes South.”

Additional Reading

Melvyn Bragg, “In Our Time: The Oath,” BBC, January 5, 2006.

I've been meaning to leave a…

I've been meaning to leave a comment on this!

The matter of the oaths seems to be hard to follow for some readers, because it runs counter to their world view, so having the historical background set out so thoroughly and clearly is sure to be helpful!

Thank you for reading and…

Thank you for reading and commenting!

As you say, oaths belong in a different world view and their weight is sometimes difficult to fathom. Little wonder the Professor had such clear outlook on their significance and consequences for the oath-takers!

No oaths, Fëanor....

Such an interesting subject, and full of real and in-universe examples. It shows quite sharply how the Oath that Fëanor and his sons take left them with no way out, no room for compromise. It is all well and good saying that the sons of Fëanor should have or could have chosen differently before the later Kinslayings, but reading this reinforces for me that they believed that they could not.

Thank you for reading and…

Thank you for reading and commenting!

Yes! Oaths had in the real historical events and in-universe a weight that is not easy to understand from our modern world perspective and which was very clear for the Professor. Once an oath was sworn, there was no going back.

Thank you for reading and…

Thank you for reading and commenting!

Yes! Oaths had in the real historical events and in-universe a weight that is not easy to understand from our modern world perspective and which was very clear for the Professor. Once an oath was sworn, there was no going back.

Excellent and succinct…

Excellent and succinct article! Thanks so much for writing and sharing this research, it is valuable context for the role of oaths in Tolkien's work.

Thank you for your comment!…

Thank you for your comment! Oaths play a central role in Middle-earth / feudal / ancient societies that it's hard to grasp from a contemporary perspective.

I still regret not being able to include Maedhros and Maglor's last dialogue about the oath (my favourite ever!) but at least I could quote Elrond who doubtlessly knew what he was talking about.

Funny you should say that…

Funny you should say that because this was actually my main source for the discussion of it in my (forthcoming lol) Maglor bio! It was super useful so thanks again for writing.

Maglor's bio! Yes!!!! My…

Maglor's bio! Yes!!!! My favourite boy!

I'm looking forward to reading it.