Tales of Thanksgiving: A Drabble Collection by Dawn Felagund

Fanwork Notes

Many are the friends and associates in this fandom who have helped, inspired, and encouraged me over the past two years. During the 2006 holiday season, I wanted to begin to thank them for the gift of their support and friendship. These drabble series were written in response to the requests and preferences of friends. The word count of each is exactly a multiple of 100 words.

Please be sure to read and heed any warnings listed at the top of each series. Most of these series are safe for all audiences, but I've gone with the highest rating just to be safe. Chapters marked in the Table of Contents with an asterisk (*) are adult-rated.

- Fanwork Information

-

Summary:

Series of fixed-length ficlets written as holiday gifts for friends in 2006. Content varies for each drabble, so please heed the warnings posted at the top of each. Adult-rated ficlets are marked with an asterisk (*). MEFA 2007 winner: 3rd Place, First Age and Prior.

Major Characters: Amras, Amrod, Caranthir, Celegorm, Eärwen, Fëanor, Finarfin, Fingolfin, Fingon, Finrod Felagund, Finwë, Haleth, Maedhros, Maglor, Mahtan, Nerdanel, Original Character(s), Rúmil (Valinor), Sons of Fëanor

Major Relationships:

Artwork Type: No artwork type listed

Genre: Drama, Experimental, Fixed-Length Ficlet, General, Romance

Challenges: Gift of a Story

Rating: Adult

Warnings: Mature Themes, Sexual Content (Moderate), Violence (Moderate)

Chapters: 25 Word Count: 11, 978 Posted on 3 June 2007 Updated on 3 June 2007 This fanwork is complete.

Curiosity

The early love and obsession of Nerdanel and Fëanor, for Angaloth.

- Read Curiosity

-

Curiosity

I.

As a child, my father said, I was but a pair of wide eyes peering over tabletops. Under tables. Into hidden nooks and corners. My fingernails had crescents of dirt beneath them from putting my hands where they did not belong. I inspected the lock and built a key and used it to enter my father's forge, curious about the wonders I might find there.

He warned me, "Careful, Nerdanel, for your curiosity will burn you!" catching my small hands reaching for a chunk of coal that--still black on the outside--upon being broken glowed red within, with fire.

II.

Fëanáro served opposite me as an apprentice, and I would watch his hands as he worked: slender and pale and quick as spiders, hypnotizing to watch, making nimble work of the most complex tasks.

But he was careless and would cut or burn himself in his haste--his curiosity--fingers welling in blisters that pained me to see. "But Nerdanel," he told me, "it is worth it!" Lifting a finger to his mouth to cool the pain. I watched his hand. I watched his lips and envied them, for possessing his hand.

And envied his hand, for possessing his lips.

III.

On the day he put light into stone, he pressed it into my palm, and I claimed light.

He folded my hands in his, always warm and no longer scarred, for he was too skilled for that now.

Curiosity: it fluttered inside of me, plunked with a hot and heavy weight into my belly and burned there.

I reached across the space between us, only my father was no longer there to warn me of my curiosity, from unseen fire within the body that I touched in reverence, closed my eyes and kissed.

Stone--light--forgotten, we claimed each other.

Strange

In the personal verse that I use for my stories, Caranthir is gifted with extraordinary abilities in mindspeak. This explores his special gifts as perceived by his parents. For Lady Elleth.

- Read Strange

-

Strange

I.

I dreaded the most the birth of my fourth-born son Carnistir, for his brother Tyelkormo had been a difficult delivery and I feared for my wife's health and safety. On the day that she told me that she again carried my son, we pressed together--forehead to forehead--nearing a kiss, but it wasn't only joy that we shared. There was fear too, something dark. The way that doors used to always close in my presence, when I was small, before the loss of Þerindë my mother. A room full of light but a dark space beneath a door that was all I could see. So was my wife's fourth pregnancy: a time of joy darkened beneath, annoying and relentless and shameful.

But yet not entirely. I'd lie beside her at night with my hand upon her belly. Upon Him, our son unnamed, and it was strange: It was as though a hand had reached back, soothed me into peaceful dreams, twining my fingers with His. It was as it had been when I'd been very small and always knew when Atar had come by my bedside for the lack of nightmares.

How, amid my fear, I slept in peace.

II.

My father had a strange gift. I'd come upon him once, sitting with Ingwë the King of the Vanyar, and they had been opposite each other as though in conversation, yet words were not exchanged. I'd watched for a long time, thinking myself hidden beneath a table covered with a long cloth. For hours, they did not speak, yet the air was busy between them, in the same way that a room alive with voices and laughter will seem to swell, like the joy cannot be confined in so small a space. I felt voices, yet I did not hear them.

But decisions were made that day. My father was to be wed again, and he and Ingwë clutched each other in joyful farewell yet spoke no word of salutation. And I understood that those awakened by the Waters of Cuiviénen were indeed the Children of the One and spoke in voices alike to that of the One that passed as rain and wind and simple laughter. Words upon a breath, wrapping a heart, raising the hairs on my arms even as they smiled, secret and silent, in an understanding that I--for all of my gifts--seemed to lack.

III.

I went to my father when, by Carnistir's first begetting day, he still had not spoken. In fact, he acted utterly contrary to what I asked of him. Clutching my legs and pushing his face into my knees when I'd become angry with his mother and asked him to leave me, to find his brother. Putting a small hand over my mouth before the words in my thoughts could wound Nerdanel further.

And she came. And embraced me. And forgave me.

And Carnistir: he scurried away and found his brother, as I'd asked.

My father laughed at my worries and lifted my strange fourth-born son. Carnistir stopped wordlessly babbling and let his forehead fall against Atar's, and for a long while, they sat that way, as though I was no longer there. Irritation tickled my thoughts, and my father's eyes opened. He laughed.

"He understands, Fëanáro, far more than you know. I expect that he will speak any day now."

On the ride home, Carnistir laid a hand alongside my face, and--strangest of strange--spoke at last in a voice clear and practiced, "Atar..." like he was the father and I the son, the one in need of comfort.

IV.

"This one is special," Nerdanel had said on the day Carnistir had been born. "This one is different."

Indeed, he was. Carnistir alone did not to weep when she left us, even in secret, the way we caught tears with the backs of our hands before they could shame us. When I was small, my father used to tell me that I wept because I did not yet understand the reason for pain. The connection between hurt and healing. Pain and hope.

I insisted: There was no connection. It was all senseless misery.

But Carnistir, he sat beside me as I wept, thinking myself alone. His fingers twined with mine, and he did not look at my face, understanding my shame, my vulnerability. He did not weep, as though he understood Nerdanel's heart better than I, her husband.

The day my mother had died, I'd sat against my father's chamber door, staring at the black space beneath. It stayed dark for so long--then a flicker. Then light.

Or Carnistir's hand in mine, warm where I was cold. His thoughts heavy against mine, recalling love, not betrayal.

He held my hand until the tears stopped.

And I began to understand.

Effortless

Maglor learns that Maedhros's gifts in diplomacy appear effortless but are anything but. For Angelica.

- Read Effortless

-

Effortless

I. The Father

On the day that Nelyo told our father that he would no longer study lore but would serve as a court page in Tirion, Tyelkormo and I pressed our ears to my bedroom wall--adjacent to our father's study--and listened, fists clenched, cringing in anticipation of the explosion that must surely come.

It did not.

Nelyo rode back to Tirion, and for a long while, Fëanáro would not speak against him, though surely, he must have believed that he'd been betrayed. The air was heavy and hard to breathe around him, but he did not speak out against Nelyo.

II. The Minstrel

As one of the best musicians in Tirion, I played in the halls and homes of the most respected of the Eldar. Nelyo came when he could, but the life of a page is simple and arduous, and he hadn't much time to spare for joy.

I was miffed, though, because my skill was rarely praised as loudly as the others. Vingarië laughed at my offense. "My dear, that is because your music is so effortless in its joy that we forget to marvel. We forget that such beauty is a gift and not simply the way of the world."

III. The Diplomat

Nelyo ascended, as did I, each in his own station. He was one of Grandfather's councilors, and his work was easy, I often thought: much walking-about in gardens and fancy suppers with lords. And smiling. Always smiling. Whereas I came home late each night, reeking of sweat, my voice raw, and my fingertips tender from the harpstrings.

"Do you practice smiling," I would tease, "in front of mirrors? To be good at what you do?" For I was slightly sickened by his success, even as he was unfailingly proud of mine.

Though he never came to hear me play anymore.

IV. The Brother

I came home one night and found Nelyo in my music room, waiting by a guttering fire with a glass of wine pressed to his forehead. "I am exhausted," he whispered. "Our father--"

Then he stopped. And smiled.

"But no mind that, little brother," he said. "I am exhausted, and all that I wish is to fall asleep to the sound of your singing, as I used to do when we were young."

Despite his exhaustion, his eyes were bright; his face untroubled.

And I knew that whatever darkened his heart would not be permitted to yet darken mine.

Sense of Swords

Finarfin's choice to follow his people into battle with Morgoth at the end of the First Age, for Ellfine.

- Read Sense of Swords

-

Sense of Swords

I.

We arrived in the Outer Lands by night, while all slumbered below deck. Except me. I stood at the railing and teased apart the blackness that was the sea and sky on a moonless night and the space between the two of them: the Outer Lands. Middle-earth. Beleriand. Those reborn among us spoke of this strange, dark place caught between the night sky and the ink-black sea. Where all five of my children had gone.

I recalled the candles carried by Eärwen after the Darkening when visiting her sister-in-law. I would sit, pressed to the glass of our window, and watch the flame flicker smaller and feebler until the darkness had claimed all sight of her. I wondered how my children had appeared from the shore: five tiny lights, going out one by one?

I wore a sword at my side: heavy and foreign, like it did not belong. I had studied with it, yes, but it was like dancing with a stranger: practiced and rigid. Holding my children, speaking with a friend, making love to my wife--those belonged.

But my hand gripped the sword as though we were familiar, the shore growing large and dark in my sights.

II.

Eärwen had not wished me to go. She never said as much but I knew. I knew in the way that she would touch me without reason; linger longer in a kiss. She'd hated my sword from the day Nolofinwë had given it to me--still more after the Kinslaying--yet she bade me to practice and even watched. Praised me.

No, I said, do not learn to love this art or my skill in it.

And she had replied, Perhaps had the children been trained ...

Catching me in a wordless embrace, amid the darkness to which we'd become accustomed.

Eärwen had not wished me to go. Yet she accompanied me to the harbor and strapped my sword to my side, as all of the wives were doing for their husbands. Four candles snuffed; four children lost. Would I be next? She must wonder. Yet her hands smoothed my tunic without trembling, and her smile was resolute.

You are very brave, she told me, and I held her close and neither had to see the terror--or the tears--in the other's eyes.

She released me first, and as she stepped away, I whispered, Nay. You are braver than me.

III.

Standing upon the soil of this "Middle-earth," it was impossible not to superimpose the present with imaginings of the past. This river called "Sirion": had my Findaráto knelt here to drink? Was this earth pressed by the boots of Angaráto and Aikanáiro? And those flowers that looked a bit thin, perhaps because Artanis had gathered of them to twine into Artaher's hair as he slept, to annoy him?

I found myself lifting fistfuls of earth to my nose. I could smell them! My children! The pang deep in my gut, of loneliness for home and times long passed: the powder we'd put on infant Findaráto's skin; Aikanáiro's toys left in the garden to become filthy during the mid-afternoon rains; the clay bowl shaped by young Artanis's hands, ugly and adored.

I cupped the dirt in my hands; made mud of it with my tears.

For the earth smelled of metal also: of blood and swords and torment in dark places, and surely, I had not allowed my beloved children to come to such grievous ends?

It smelled of the sword at my side that I held tighter now in muddied, ignoble hands as I marched, fearless, forward, into the darkness.

Of Love, Mischief, and Flowery Prose

Another in the series of endless speculation about the relationship that might have existed between Maglor and Celegorm, for Rhapsody, who adores them both above all others and is largely to blame for my similar fascination.

- Read Of Love, Mischief, and Flowery Prose

-

Of Love, Mischief, and Flowery Prose

My brother Macalaurë is in trouble with our father most often of any of us. I am rambunctious, Nelyo is contrary, and Carnistir is downright mean (or so Atar says), but it is boring Macalaurë who is in trouble the most.

Occasionally, it is my fault.

Occasionally.

For I adore--absolutely adore, in the same way that I adore strawberries, swimming holes, and newborn hound puppies--annoying my second eldest brother. Annoying him until his ears turn red and he wastes his pretty voice on screaming not-so-nice words at me. That Atar inevitably hears. And punishes him for.

Then, later, I think of it with regret, for Macalaurë is kind (usually) and rarely deserving (truly) of my mischief. Like when I knew that he was to meet his girl-friend on the morrow and spent the whole day washing and pressing his best clothes and even wiped the mud off of his boots, only to have me trip the next morning while running from Carnistir (who was trying to bite my hair) with a cup of grape juice and--

Well, it was an accident that I tripped. It truly was. However, I could have aimed for the big expanse of floor that would have been easy to wipe up instead of Macalaurë.

White tunic turned purple and grape juice dripping off the tip of his nose, Macalaurë called me "cur of Oromë" and other things that I am too young to hear, much less repeat.

So Macalaurë did not see his girl-friend that day. He was permitted to make his excuses and send a letter of apology, though Atar read it first and made him rewrite it three times for whining too much or being senselessly malicious or being too sentimental. Macalaurë's excuse for the latter complaint was that he merely wished her to know that he loved her. "She knows," Atar said, "without flowery prose." For my role in the hubbub, I was to deliver the letter to our neighbor, who was going to Tirion and would see the letter received by Vingarië.

I was sent to Macalaurë's bedroom to collect the acceptable fourth attempt at a letter. His eyes were red-rimmed, and he shoved the letter into my hand without a word or glance. He was back to wearing his boring gray tunic and trousers, and the ones I'd ruined--made clean and pretty the day before--were balled up in the corner.

I will admit: I felt bad then. But my stubborn tongue would not twist into an apology, and I left Macalaurë alone, letter in hand, to go to the neighbor's.

It was a beautiful day at the start of autumn, yet I'd ruined it for my brother. Skipping along, enjoying the warm breeze and midday Treelight, this gave me pause. And when I paused, I saw that the autumn orchids were in bloom, nodding violet heads over the road.

Carefully, I affixed one to the letter. So that Vingarië would not doubt that Macalaurë loved her.

Hands and Voices

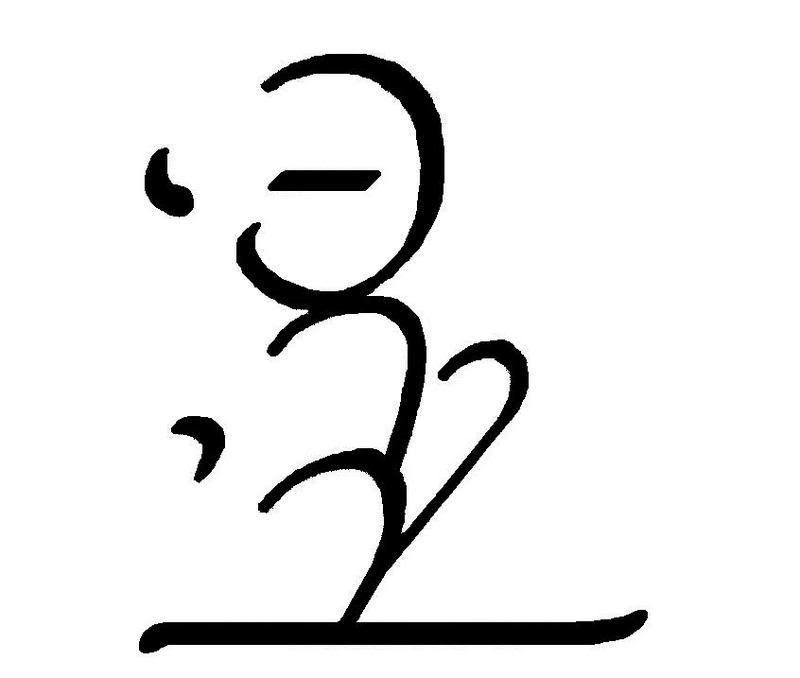

The creation of the Sarati by Rumil, for Tuxedo Elf. The illustration at the end of the 500-word quibble is the word that Rumil writes and was constructed using the Sarati reference by Ryszard Derdzinski.

- Read Hands and Voices

-

Hands and Voices

We were given hands and voices by The One so that, with them, we could create beauty. Or so we were told by Ingwë, who sat at the head of the fire and told us these things.

Hands and voices: each of us given two of the first and one of the second for making beauty. One I'd been given, great and exquisite, but the other two I seemed to lack. I had hands, of course, but what came of them was not beautiful. Others crushed berries and dabbed patterns upon surfaces of rock. Or they squeezed clay dug up from the riverbanks into shapes like Quendi and gave both as gifts.

Ingwë told us that The One had built us of the sand beside the lake, upon which we'd awoken. That is why our eyes sparkled in the starlight and why our skin was soft and supple, not coarse like the pelts of the beasts that prowled just outside the circle of our firelight. That is also why we were strong, he said, for one could not crush sand in his teeth, and the cleverer among us had even begun to rub it on rocks to shape them in new ways.

I was not skilled enough for that.

So I never had gifts to give. I could lift my voice in song, but the gift was ephemeral, gone and forgotten by my next breath, whereas the rocks and clay were cradled in hands and loved even as the shifting stars blew across the sky overhead.

This grieved me.

It grieved me for there was one whom I sought to give a gift, only she was not built of sand like me, but made of water itself, able to take a single point of starlight, spread it thin, and throw it back one-thousandfold. I never dared say it aloud, but I believed that the water, then, was more beautiful than the heavens and all of the stars. And she was more beautiful beside, taking a single point of happiness and making joy one-thousandfold.

I adored her. And I had no gift to give.

Many songs I composed, but the wind tore them apart. Lying upon by back beside the lake, I thought of her. My songs of her. Just as the sound of water made me think of shimmering waves or the wind in the trees made me see a ripple of starlight upon leaves, so the thought of her song made me think of her. Made me think of the moment I'd awakened-life breathed into sand-and saw her with her back against a tree and the sickle-stars bright in the sky overhead.

My first thought had been: I love her.

Love her.

Love.

Even my clumsy hands could take a shard of flint and chip away that shape into the face of a softer stone: the sickle-stars bright above the tree, the place where love had begun. And so I named it, my gift for her: love.

In the Sarati, the spelling of love:

*The Space between Hearts

Maedhros's captivity from the perspective of Caranthir, for Oloriel.

Warning: This drabble contains violent imagery that some readers might find disturbing.

- Read *The Space between Hearts

-

The Space between Hearts

I.

How did you forsake him? Your own king? Your own brother?

These questions were never asked outright. But we Noldor had gotten good at not being heard and yet hearing rumors borne upon the wind. I saw Nolofinwë's people watching us in the days following our reunion, their lips set stern and silent. It was their eyes-their hearts-that asked it: How?

And I heard.

How then? Not easily. Least of all for me, Carnistir the Dark and Silent, whose blackened heart was said to have tipped the decision about Nelyo in favor of forsaking him to Morgoth's cruelty.

II.

The rumors were many and varied, and I heard them all: whispers of thoughts exploding in our wakes as we walked the streets at Nelyo's bidding, greeting people over whom we no longer presided.

It was said that Tyelkormo had lusted for the crown and thought that with Nelyo removed, Macalaurë would be easily overthrown.

Or Macalaurë: he had sat long in agony and indecision, paralyzed by his own cowardice.

Or that I had reminded my brothers of our oath to the Silmarils and that we had made no such oath to Nelyo.

The truth, of course, is much different.

III.

For what outsider knows what happens in the secret darkness between the hearts of kin?

It is said that we do not begin to remember until we are a year of age, yet I remember that Nelyo was the third to hold me after I was born. I remember that in the silver light of his spirit, there was never a need to cry.

I do not remember Amil or Atar. But I remember Nelyo.

His lips were warm against my forehead and a whisper--I love you--the words of which I did not understand. The meaning: I did.

IV.

I never measured my love for Nelyo in kisses and kindness, as most do. We rarely spoke but we knew. It was there, in the space between our hearts, where words dissolve and become meaningless.

In the days of his torment, I went to him every night. He was not hard to find, for I had known that silver light since the day of my birth. He was a beacon in the darkness of Angband. I went to him and watched as they burned him, whipped him, and broke his bones. I endured it with him, while the others slept.

V.

He spoke to me sometimes.

"Carnistir. Go."

The other prisoners thought him delusional: a king from over the sea who was tormented more than most, speaking in strange tongues to the empty air.

"I do not want you to see this. Me. Like this." Legs grown thin and scarred, bound wrist and ankle, body naked, stretched and waiting. My thoughts reached for him, and I stood beside him. I would endure what he endured.

But I would not speak of it. Even to our brothers, though they asked with their eyes. The ████: it lived in the space between us.

Eru's Blessing

Nerdanel announces her marriage to her father. For Allie.

- Read Eru's Blessing

-

Eru's Blessing

My father was not pleased; I could see it in the way he bustled around the workshop, keeping his hands busy and his eyes from meeting mine, as though afraid that the hands would betray him and tremble--or maybe strangle my young husband waiting outside--or that his eyes would show the depth of his disappointment in me.

But disappointed or not, it was too late: We were wed. Married with neither blessing nor permission, in the wilds of the forest between Tirion and Formenos with only the witness of Eru.

"The King--does he know that his firstborn son has taken a bride?" He was turning a mold in his hand, calloused thumb searching for imperfections along the surface. "Taken a bride without his blessing, like a heathen in the Dark Lands?"

The mold: cast to the table with a clatter. I winced.

Fëanáro had wished to come with me so that we could deliver the news to my father and his master, side by side. I had grown accustomed to having Fëanáro at my side in the past three years; grown accustomed to letting him be strong when I lacked the will. To letting him speak first. But this I had to do alone, to remember my strength as a woman and a daughter, not a wife.

"We had the blessing of Eru, Father. And we--I believe that that was enough."

His gray eyes were cold as steel upon my flushed face. I could see him appraising my well-being and finding reason to fault Fëanáro. I kept my arms crossed over my body, lest he notice how I'd changed. His voice quavered on the brink of anger. "You have become proud, Daughter--like him--to think that you know the will of the One."

"In this matter, Father, I do," I whispered, and I waited for him to cast me forth from his workshop, to denounce me as his daughter for such blasphemous behavior.

But something interrupted us then: a thin cry that made us both turn to find Fëanáro at the door, gray eyes wide and voice reduced to a near-whisper. "I am sorry to interrupt. But he wants his mother."

Passing to me little Nelyafinwë, who stopped crying at my touch and settled against my breast. My father's eyes widened, and I knew that he understood. And never again would he question Eru's blessing.

From the Doors of Night

Young Maglor gets a special gift from his father, for Appoggiato.

- Read From the Doors of Night

-

I.

It was nearing my begetting day--within a fortnight, even--when my mother failed to rouse me for breakfast one morning, and I found her sitting at table, having sent my brother to his lessons with a banana and cup of milk. Her eyes were red. She looked weary.

"Where is Atar?" I asked, climbing on her lap. Her arms closed around me, but it was more reflexive than anything, like blinking when something came at your face.

"He has gone off." Rubbing at her eyes suddenly and drying her fingers on her skirt when she thought I wasn't looking.

II.

"Where is Atar?" I asked Nelyo, who always worked at his books but worked more when Atar was "gone off."

"Gone off," he answered, and his face clenched in concentration.

"Gone off where?"

He sighed. "The Doors of Night. Be gone, Macalaurë. I am busy."

I snuck Nelyo's lorebooks and read about the Doors of Night. A black sea, it said, and darkness impenetrable. I thought of the darkness beyond the doors of my closet and shivered for Atar, who had scared away the blackness there once with a lantern--and the fear too. I hoped he'd taken enough lanterns.

III.

The Doors of Night, I read in another book, are the only place where blackwood trees grow, producing wood of astonishing quality.

Atar came back and took something to his workshop and didn't appear again for many days more. So it was like he was never back at all. Amil was still sullen and Nelyo still worked at his books, and I wondered what he'd brought. Certainly not blackwood. Atar didn't care much for working with wood. Too easy, he said.

My begetting day drew nearer and nearer and then it was tomorrow. And it seemed that everyone had forgotten.

IV.

We had breakfast on my begetting day and were a family again. Even Atar came, though he looked tired from many days of ceaseless labor.

"Would you like to receive your gifts after breakfast?" he asked, and though he was exhausted, his eyes gleamed like adamant beneath dust so you know that--though dirtied--it is something you should treasure.

He hastened from the room, before I could answer, and returned with my gift: a harp made of blackwood brought back from the Doors of Night.

His eyes brighter than adamant, as though my joy had washed his exhaustion away.

Shattered

The devotion and obsession of Finwë and Fëanor, for Aramel. "Shattered" was recently translated and published in the Croatian fanzine Olórë Mallë.

- Read Shattered

-

Shattered

I.

When I was small, I made a gift for my father on Awakening Day. I stole a trowel from the gardener's shed and stomped my feet about the garden until thump-thump-thump, they came upon clay. Triumphantly, I extracted my prize from the earth and made for him with my own small hands a vase that I imagined worthy of holding the most beautiful of Yavanna's flowers.

I got mud all over my hands and face that day, and I had to be given two baths because the first tub of water turned so muddy that it covered my whole body in a scrim of dirt that had to be washed away in clean water. And the gardener loudly lamented the patch of lawn I'd ruined--until my father silenced him with a stern glare, that is.

For he was proud of me. He took my vase and placed it in at the top of the stairs, upon a small table, where all could see. Not even on the family floor, where I had my bedroom next to his and no one went but us two and the chambermaid but the lords' hallway where all could see my gift and marvel.

II.

Not long after, my father announced that he was to wed Indis of the Vanyar, and all of the halls of my father's home became unhappy for me. The family hallway was no longer a place for just my father, the chambermaid, and me because Indis was there now. In my father's chamber, next to mine, where I could hear her voice answering his in laughter, and I thought, Imposter! Sycophant! and my stomach twisted until I was sick in the basin.

But the lords' hallway was worse. There, my father's marriage was a happy thing, and my attendant misery was thought strange and malicious. Manipulative, they called me. The lords began to avoid me, and I went there only to listen at doors, where strange words united my father and Indis. Not love: Well connected. High family. Politics.

Good politics. Good politics accompanied by glossy smiles that I could not mimic and soft grasping hands. My hands were growing hard with calluses.

Soon, I went there no longer. And I was more than glad to forget my vase--I had learned in my lessons with Aulë that it was mostly mud anyway--and the love that had inspired it.

III.

On the day of my exile from Tirion, I spent long hours in my father's study. "It was not my choice, to exile you," he said, but I knew--even as he said it--that had it been, he would have seen me exiled anyway.

It was the last time that I would pass down the lords' hallway, though I did not then know it. I was leaving the city. Leaving him.

But at the end of the hallway, I paused. It was still there: the vase. Still sitting upon its table at the top of the stairs, as ugly as the day I'd made it. I lifted it in my hands. I hadn't even bothered to varnish it, and that it was made of mud--not clay--was sadly evident in the grit it left on my hands.

From behind me, my father's voice: "Fëanáro?"

I lifted the vase over my head. And hurled it down the stairs.

Footsteps rushing towards me and Father's voice, "Fëanáro, I am--" The vase rolled and bounced on each step and would not break.

"--I am coming with you."

Unharmed, it rolled from the last step to the floor. And shattered.

*Hatred

Of hatred and passion between two cousins, for Mirien.

Warning: This is a slash story. It is not sexually graphic, but it is not for the faint of heart.

- Read *Hatred

-

Hatred

I hate him.

My eyes are drawn to him upon entering the clearing. It is the Winter Festival, and swaying lanterns are strung amid the trees and bonfires paint the people in a feral, throbbing light. There he is, hair the color and texture of flame; silver eyes bright in the darkness.

I hate him.

From across the clearing, his gaze is drawn to mine, and we stare for a long moment before he turns and moves away and lets the shadows swallow him. I see a lick of scarlet hair as he disappears. Amid the churning bodies and dancing flames and trees that bend with the rhythm of the drums, it is all that I can see.

Until the darkness claims him.

Yet we are destined to meet. We always have been. Coming together out of duty, then friendship. Now--

Hatred.

The eldest sons of the high princes cannot linger long on the periphery, and so it is inevitable. We are held tightly in the dark clutches of the crowd, moving to its center in slow jolting starts. I see him dancing with a maiden, long-fingered hands pale against the dark silk of her gown, pressing into her warm flesh beneath. He bumps me, and I seize that long fire-bright hair, defiant.

Passionate.

He strikes me in defense, an open hand across my cheek, a sound that falls between the relentless drumbeats. He wears a ring on that hand, and it cuts my face in a stuttering line. I am staring at his mouth, thin lips that I have not seen smile in a long, long time.

My fingers become a fist and meet that mouth, darkening his lips with his own blood.

Strong arms seize me from behind, just as he is seized by Macalaurë, and we are dragged apart. The cut on my face is throbbing in time with my heartbeat, matching the drums, then faster. Frantic. His blood is upon my knuckle, I see, when the crowd swallows him again and I can spare a glance for someone other than him.

Red blood on white skin.

Turukáno releases my arms with a disgusted admonishment before returning to the arms of his wife. The cut on my face throbs faster until it is just pain. Will it leave a scar? I hope that it will.

I lift my fist to my mouth and lick away his blood.

Falling/Forever

How Caranthir met and fell in love with his wife, for Kasiopea.

- Read Falling/Forever

-

Falling/Forever

I. Purple

She loves purple.

She lifts an orchid to brush against her face, smiling, savoring. Or stares into the east, where the black sky and silver Treelight and reflection from the sea made a purplish hue along the horizon.

I lie upon my back and count the numberless stars overhead--or at least I pretend to. Really I am watching her.

A slender hand extends to the east, as though she can gather that purple sky and bring it to her. I think of armfuls of purple flowers bound in ribbons of the same and wonder ...

But no. I don't dare.

II. Unsound Emotion

I tease her about it because she is not the sort to adore such a dainty color, preferring to ride hard alongside her brothers during the Spring Hunt to sitting primly like the ladies in Tirion, drinking spiced tea from mugs trimmed in purple.

She punches me for my insolence, hard jabs delivered to my side, knuckles and ribs. Bone and bone. It hurts and leaves bruises spreading beneath my skin, blue edged in purple.

"Look," I say, lifting my shirt. "Your favorite color!" and this time, she pinches me under the arm.

"That mark," she explains, "will be red."

III. Black

"Purple," she tells me, "is better than black."

For I adore black and wear little else. "It is easy to match clothes in the morning," I explain, "and I don't have to worry about stains."

But purple, she says, is the color of nobility. Of honor and courage. And of proper love, not the sort defined by red and ruled by unsound emotions but the kind that lasts over ages, as trusty as a heartbeat.

Purple is the color of beauty--not youthful, frivolous beauty--but the kind that doesn't fade.

And at last: Purple is the color of forever.

IV. Falling

"Then what is black?" I ask her.

She answers: darkness, nightmares, the end of the world. Black is the color of falling.

"Nonetheless," I tell her, daringly, "I think that you would look nice in black."

Both of our faces turn red: the color of unsound emotion.

There is a festival coming up in celebration of spring. The beginning of spring or--she says--maybe the ending of winter. "Are they different?" I ask, and she shrugs.

"Perhaps."

Though winter lingers, flowers are already emerging from the soil, and I am careful not to tread them. Especially the purple ones.

V. Forever

I dally long before making an appearance at the festival, for I feel silly. And I look silly too, judging by the way my brothers glance quickly at me and look away, careful not to laugh.

I suppose that purple is just not my color.

And the one for whom I wear it is not even here.

I am about to return to my chambers and exchange the purple tunic for a black one when I see her. Her face is reddened, like mine, and she wears a black gown with purple flowers affixed.

The colors of falling. And forever.

The Lesson

An alternate-universe quibble that considers the possibility of love between Caranthir and Haleth, for Unsung Heroine.

- Read The Lesson

-

The Lesson

I gave her a sword and taught her how to use it. Because I feared for her, I said, and her safety as the chief defender of her people. Folding my hand over hers, adjusting her grip in the hilt. "That is correct," I said, yet I did not want to let go, for I loved the touch of her skin. Her pale hair, eager face turned to mine. Freckles across her nose, giving an illusion of perpetual youth but for her gray eyes far too grave.

"Once," she told me, "my eyes were blue.

"Then my father and my brother died."

Yet it was a midsummer's day, beautiful, with a sky so blue and untroubled as to sear the eyes of one who gazed too long upon it. "Today is a day full of hope," I told her, tightening my hand on hers, "and thoughts only of the future."

How I longed to see her turn to me and smile as her eyes met mine. Blue eyes met mine. I adjusted her stance. She resisted my touch, then succumbed. She moved with me, flesh no longer resisting the touch of flesh. Slowly, she parried with me. Like dancing, I longed to tell her, but I suspected that she knew nothing of that.

She was but twenty years old--young in the years of her people and a mere babe in the years of mine--yet there were lines beside her mouth from too much frowning.

I counted carefully, and she matched her steps to my voice. For each count, my heart pounded hard against my chest, three times. Sweat prickled beneath my light armor. Yet her movements were careful and studied, and I knew that she was not watching the way that my body danced so perfectly through the air, as light and graceful as a breeze. Our blades knocked together in an awkward, reluctant rhythm.

Her lips followed my count--one, two, three--but she spoke no word.

Her people had come with crude weapons: knives chipped from stone and heavy hammers that wearied one's arm to wield. Nay, a sword suited her better: a beautiful weapon that complimented her grace and intensity. We began to move faster. She was seamless, boneless. Beautiful.

Yet no match for my skill. When the pace quickened yet again, I easily disarmed her and stood upon her blade in the dust, watching the way that her chest rose and fell rapidly inside her leather armor. The sheen of sweat on her skin. Her eyes turned to mine and reflected the blue sky, and for a moment--

Quavering fingers touched my face, a thumb tracing the contour of my cheek. Her lips were damp and slightly parted, and I lowered my face to hers for a kiss.

I felt it then: a jolt as her lips met mine and the kiss of stone, having cut through my armor in a single swift stroke and coming to rest--cold--against my bare skin beneath.

Lore

One of several possible versions of Maglor's fate, for Sirielle.

- Read Lore

-

Lore

He closed the book with a snap. "That is it," he said. "The history of the Eldar."

The girl glanced up at her tutor. Disappointment gleamed in her eyes. "But I do believe that you've forgotten a bit," she said. She was a smart girl with straight shoulders and a forward way about her, but she was used to getting what she wanted. Mystique, romance: she was at the age for fairy stories, for frozen princesses and wicked queens.

And lost princes.

But her tutor only smiled. "I have not forgotten a single word. The texts you have read are secret, granted not even to kings. Yet I have found them for you. They contain all that is known."

The girl thought about this. She stared out the window. It was winter, and the light off the snow made her face look graven, aged.

"But what about Maglor?" she blurted out finally. Eyes widened, smile youthful and naïve, the illusion was ruined.

"There is nothing to know," he gathered the book into his arms, "and so I do not teach it." He strode from the room before she looked too deeply into his face. Before his own illusion was ruined.

Magic

Another version of Maglor's fate: how he sought redemption for his misdeeds.

- Read Magic

-

Magic

I.

There was a legend in the town by the sea, a legend of restoration. Redemption.

People came from all over, broken treasures cradled in hands: watches, vases, rings. Dolls and wagons, broken during childish fits, then regretted.

"Leave it there, in the sand," they were told. "When you return upon the morrow, it shall be restored to you."

One widow brought the locket her husband had given her, the picture having been ruined long ago. She buried it in the sand, as instructed.

Come the morrow, it was fixed. Caught in the heart was a single strand of chocolate-colored hair.

II.

One boy was cleverer than most. He always had the answers at school, jabbing his hand into the air before the other children could answer. And he was determined to learn the secret behind the "magic."

He crept out at night to watch the beach. He'd buried a fountain pen in the sand, having broken it over his knee that morning.

But he was surprised by a hand on his shoulder and his mother, her sour face tender, somehow, in the moonlight. "Come home," she said, "and do not worry him. Do you not see? Knowing--that would ruin it."

III.

The children raced to the beach. It was not a trinket in their hands; it quavered, eyes darting with fright.

The seabird with the broken wing had been found, pecked by gulls. Its fate had been debated, and it had been decided that it should be trusted to the magic.

Carefully, they covered its feathers in sand.

Come mid-night, the man came. Long-fingered hands sifted the sand, found the bird. It had stopped trembling.

Rising to face the moon, he opened his hands and set it free. That which winked in its grasp--? Nay, it was just a star.

Belief

This final quadrabble about Maglor's fate attempts to combine his legend with the modern legends surrounding Christmas.

- Read Belief

-

Belief

The orphanage was a formidable place, rising from the cliffs that soared over the angry sea. Its hallways were labyrinthine, cold and damp, with drafts that came from between the stones and put rattles in their chests. "Witches' fingers!" chanted little Samantha when the nuns weren't looking. "Witches' fingers! Witches' fingers!" But all of the children--even Samantha--feared the witches' fingers above all else, for some of the children's chest-rattles had become blood, and they had been sent to the sanitarium, never to return.

Three of them were close in age--neither little and tearful nor big and sullen--and they snuck out at night and knelt on the cliff that hung over the sea, watching the water dash itself upon the rocks. Just visible to the east was a strip of beach, and the children imagined where it might go, when it tapered out of sight around the cliff.

"To a castle!" said Nathan and Thomas cried, "To the lair of a dragon!"

"Away from here" was Samantha's reply.

On one night, the clouds were low, and fat snowflakes spiraled slowly to the earth, and the three children crept from their beds and went to the cliff, both frightened and exhilarated by the great height and the occasional surge of wind that snapped their nightclothes like banners on the breeze. Numb fingers clutched the rocks and peered at the water--and the beach--beneath.

"Tonight is the night of magic for children," whispered Samantha, "when the Wandering One comes and leaves a beautiful item for each of us. Sometimes pearls or sometimes gold from ships that have foundered. Special things, that come from the sea."

Thomas snorted. A skinny, mistrustful boy, he scoffed at such storybook notions, and Samantha was prone to whimsy. "And why would he do that?" he asked.

"For once, long ago, he tossed the greatest treasure known to the world into the sea. And since then, no beautiful thing can touch his heart, and so he gives them freely to others, who shall find joy where he cannot."

The children's breaths steamed in the darkness as they squinted at the beach and the churning black sea. It was Nathan--sharp of eye if not of mind--who gasped and pointed. "Are there footprints? Upon the sand--?"

"Of course there are," Samantha breathed with a smile, fingers tightening on the rocks. "If you believe."

The Wanderer

Young Finrod's first taste of wanderlust and his first friendship with his older cousins. For Pulsarkat.

- Read The Wanderer

-

The Wanderer

Findaráto waited and chose the perfect day for his journey, a day when he was trusted to the imperfect watch of Cousin Findekáno, who was more concerned with writing letters and gazing at the clouds.

Carefully, Findaráto put the necessary provisions into a pack. He took a lump of bread, a waterskin, and a blanket. He even took his bow because the wanderers in stories always had bows, even though he didn't have any arrows. But he liked the way that it looked, tossed over his shoulder with his favorite blue cloak that he liked to call his "traveling cloak"--at least in the secrecy of his thoughts.

He'd found a long, straight branch and hidden it beneath one of his father's topiaries, unkempt and likely a safe hiding place. As his cousin sighed at the clouds, Findaráto crawled beneath the scraggly green rabbit and saw that his father had not disappointed him: the branch was still there. He walked with it because the wanderers in the paintings in Grandfather's Hall of History always had walking sticks. And he liked the sound that it made between footfalls. Tump. Tump. Tump. He strode with a purpose through his father's gates. His father had once said that one could go anywhere without suspicion if he went with a purpose. He said that he'd heard his brother say that once and found it to be true.

"Uncle Nolofinwë?" Findaráto had asked.

"No," his father had replied. "Uncle Fëanáro."

Who was Uncle Fëanáro? Findaráto often wondered. Was he like Uncle Nolofinwë and somehow more solid than either of Findaráto's parents? With an embrace that was like being tucked into bed at night, both safe and warm?

"Rather like that," his father had answered, "yet not quite."

But the lost uncle knew that to walk with a purpose allowed one to walk anywhere, a piece of wisdom reminiscent of something that Uncle Nolofinwë would say.

Yet not quite.

Down the street he strode, his walking stick making a light tump-tump in time with his footsteps. He was stopped once by a shopkeeper, who asked where he was going and gave him a piece of sugar-candy when he answered, "To find lost people in distant lands."

He made it to the bottom of the city and across the plains where the King's riders practiced. He stopped to watch them only for a short while; 'twas better to view them from upon his father's shoulders. The forest lay above the plains, and it was dappled with Treelight and shadows, but Findaráto easily found the road, and he tump-tumped along the road until the Trees grew dim and his belly began to warn him that suppertime drew near.

There was a clearing up ahead, and he thought it best to pause there, upon the relative comfort of the soft grass. There was motion between the trees: a flash of color and a quick laugh, abandoned and joyful, like when his mother tickled his father beneath the ribs. Findaráto strode forth, to hail the strangers.

There were two of them, and they paused, wooden swords at their sides. One had hair of a strange color, almost red; the other was dark-haired and smaller and quick to smile.

"Findaráto?" said the taller, the one with the strangish hair. He came and lifted Findaráto in his arms, like Findaráto's father would have done. The silvery star at the throat of the smaller one was familiar somehow. "I have come far to find you," said Findaráto solemnly, hungry and wearied--yes--but content, "though it seems you are not strangers at all."

*The Mirror

Fëanor's self-love and -loathing following his estrangement from Nerdanel. For Alina.

Warning: This story contains both sexuality and violence.

- Read *The Mirror

-

The Mirror

I.

He would never want another to see him. Not like this.

I watched him as he studied, as he moved around the room. As he lay upon his bed and allowed the blank, white ceiling to become a backdrop for his dreams. I set up mirrors everywhere to better watch him. Sometimes, he broke the mirrors; all the better, though, to observe single facets of him. A hand, a chin, a hip. His eyes. His lips.

Lips that turned into a frown, for he knew that I watched. I traced my fingers along the glass and imagined them smiling again.

II.

A sculptor knows her subject with a special intimacy, Nerdanel used to say. I'd found her sculpting me once; wondered why she'd blushed. Molding my legs from clay, a tiny fringe of toes, a foot cupping her fingertips. She'd yet to touch me then, of course, for we were both still very young, but one day, she would.

Her hands were always wise upon me. Nothing about me ever surprised her.

My statue, I would do in the nude, as Nerdanel had not dared to do. Not at first, anyway. I watched his robe slip from his shoulders like water. He had a strong back and a narrow waist. Firm buttocks and long legs. I caressed him in my mind, flaws and assets both. I thought that there were more of the latter than the former, but I doubted that he'd agree.

Touch yourself. And let me watch.

His head tipped forward. He was ashamed. He shook his head vigorously--No!--hair falling in his face, his beautiful face, colored by his humiliation with eyes closed--yet I saw.

He was already hard, his hand slipping up the inside of his thigh, the tears on his face bright as diamonds.

III.

A special intimacy.

There he laid, upon his side, cold flesh left too long without love. In his dreams: the lover who had once known him with "special intimacy." Had known, too, how he would hurt upon her leaving.

Yet left anyway.

He had strong wrists with delicate bones, and she'd once caught them--thumbs upon his fast-thrumming veins--drawing him into a kiss. He took those wrists as hard as he could against the headboard of his bed. To punish himself. To empower himself as one capable of hurting him worse than she had. To make his body into one she did not know.

His flesh bruised and swelled. Bled even. Sleeves worn long, only he knew. She did not. He'd erased that "special intimacy."

Watched in the mirrors as he carefully caressed damaged flesh. Loved it. Kissed his wounds, lips red with blood as they'd once been with wine, in his days of joy with her. Learned to command the pleasures of his body as she had, only his study took him in different directions, where pleasure lay on the boundaries of pain, where she'd never gone.

Until the day she'd left, of course.

He finished her work.

IV.

And now: the statue.

For I'd watched in mirrors long enough now. It was time to prove that special intimacy.

I made him in steel. Eyes closed, I caressed the shape. Or hammered upon it until my arm ached.

It is hard for me to sculpt you, Nerdanel had said at the end of our marriage. I know you too well, and nothing is ever right.

But I knew the lines of his body. The beat of his heart; the color of his blood.

Or--my nose touching his, eyes lowered in shame--the way he looked in the mirror.

Gladly

Three hopelessly romantic drabbles about Amrod, for Isil.

- Read Gladly

-

Gladly

I.

When I was small, I asked everyone I knew: What is love?

"Love can't quite be defined," said Nelyo, though he gave me a list of novels, paintings, and treatises that made a decent start.

"Love licks your face and you don't care that he was just eating rabbit scat," said Tyelkormo.

"You die for love," said Atar. "And gladly."

"Love is us, Ambarussa" said Ambarussa.

Lastly, I went to Macalaurë, recently wed and poetic beside. "Love is when everything stops"--he stopped, breath held--"and you can feel the world spinning. And you know that love moves the world."

II.

My life never stopped, and I found myself at Doriath with little idea how I'd gotten there. The refugees were being removed, marching before me, tired eyes fixed upon the ground rather than me, part-destroyer of their homes, the sword at my side still wet with the blood of their brothers and husbands.

Love doesn't move the world, I thought. Swords and lies and hate move the world.

But then, she was there, walking before me.

The world stopped.

Wind, birdsong, my brothers' shouts--all stopped. My heartbeat ceased too, and I might have died there.

But she marched on.

III.

I kept thought of her secret. Nelyo spoke of oaths and loyalty as reasons to march upon Sirion. I agreed to go, but it was not a Silmaril that had my heart or my loyalty. And when we reached the city, my sword stayed bright while others were made filthy by the blood of kin.

I found her in a cottage. She was not craven and wielded a blade with awkward determination. "I fight for peace," she told me, and I answered, "I fight for you."

My father's words made sense then.

Gladly, I tossed my sword at her feet.

Blinded

Fingolfin and his herald at the first sunrise, for Phyncke.

- Read Blinded

-

Blinded

I.

We made a lot of clichés in Aman without much of an idea of what they really meant. "Blinded by love," we said. Or: "Blinded by rage." Grief, beauty, deception.

In Aman, we were always blinded by something.

We had no idea.

What was it like? I was often asked when we met the first Moriquendi, about crossing the Ice. Not the lovely, coddled people of Elwë but the Moriquendi of the cold north, who had gone so far as the Helcaraxë, seeking loved ones ensnared by Melkor, but quailed and turned aside. There was no cowardice in turning aside, I learned. They were a hardy people who feared little yet would not step upon the Ice.

The Ice? How was it?

I remembered little of it. Just a narrow vision of the east. The east, and a particularly delicate pattern of stars on the horizon. I saw only that. I was blinded to all else.

Blinded by what? I did not know.

I remembered only the sound of my breath, too loud in a land otherwise without sound, and the pattern of stars on the horizon.

And a hand upon my arm. I remembered that too. But whom--?

II.

My herald.

I dreamed of it--the Ice and him, my herald.

He'd been but a boy when he'd knocked upon my door, eyes wide with hope. He was not an attractive boy; he had freckles and overlarge elbows. "I want to be your herald," he said.

"You are far too young for that." I closed the door in his face.

Not long after, I needed a herald, for I was king. I pondered this but how does one go about getting a herald? It seemed a job unworthy of being trusted to a stranger.

He came knocking again. He was still freckled but had grown into the awkward elbows. "You need a herald," he said, "and I wish to serve as one."

At times, I will admit that I wondered why I'd agreed. He was ugly and didn't even look like a Noldo. His hair was golden and his skin too pale and his voice wasn't quite strong enough to announce me. When we reached the Helcaraxë, I told him to stay behind, convinced that he would die otherwise.

Yet he had not. It was his touch upon my elbow, as constant as the stars that kept my course.

III.

Turukáno had protested him the most. "He is ugly," he said. "And he makes a fool of us."

Yet it was for Turukáno that he'd disassembled my banner, to wrap him as he'd clutched Idril, weeping for Elenwë lost to the Ice. When we'd marched onward, he'd guided Turukáno and me. "I have two hands," he'd said.

I saw only the stars on the horizon. Not him and not Turukáno. I spared no thought for love, to have it lost upon the Ice.

Or lost to treachery.

Do I need a herald in this dark land? I wonder sometimes. Still, he is there, at my side, as we ride to my brother's camp. Though my brother is gone; Macalaurë's banner flies in its place.

Upon the eastern horizon, the stars are growing faint. We stop--my herald and I--and wonder at the quivering fire that eases slowly out of the darkness at the end of the world. The light strikes him full in the face and sets his hair aglow like molten gold.

His hand--lacking the banner--clutches mine. The stars are gone but in the light of the first sunrise, I do not fear losing my course.

How to Paint a Star

Young Fëanor reaches for the unattainable in this quibble for French Pony. "How to Paint a Star" was translated and published in the Croatian fanzine Olórë Mallë.

- Read How to Paint a Star

-

How to Paint a Star

From where comes the light atop Mindon Eldaliéva?

This is the question I ask, the reason that I rise before the King--my father--even, to sneak atop the palace and gaze upon the Mindon. To ask: How is it possible?

The wind is brisk up here. It took a while to climb: first the lattice in the garden and then the windowsill to the loose brick that slipped from my fingers and fell a long, long way to break on the terrace below.

I feel fear, like the blink of an eye: a wince and darkness. Quavering fingers pressed to the bricks, I look at the Mindon and cannot be afraid.

From the loose brick, I move to the next-higher window; then I am at the stones, and it is a bit easier, all the way to the top of the palace. I still have to tip my head back as far as it will go to see to the top of the Mindon, where the light glows, blurry in the early-morning mist as though rubbed by a hand. The tower twists to meet it. Against the night that lies thick above the wan morning Treelight, the tower is very pale. I stretch my arm beside it until my elbow pops and hurts. My arm, too, is very pale against the darkness, and I wonder: Maybe the Mindon had been an arm like mine, stretched thin and grown stronger over the years?

From where, then, comes the light?

My father says that Varda made the light, just as she'd made the stars. Upon the shadow-side of Tirion, the stars burn so brightly in the sky that even when I close my eyes, I see their shapes, red-gold against the insides of my eyelids. I can't sleep on that side of the city, not knowing that stars are overhead. As soon as the door snicks shut behind my father, I am out of bed and leaning from the window to memorize their shapes in the sky.

But if the Mindon is but another star, then what does that mean? Are not the stars supposed to be unattainable, destined to be strung between my fingers as I stretch my hand against the night? But the Mindon--I put a slippered toe between the bricks. For a breathless moment, it holds me. Then my foot slips away, and I fall back to the roof. My heart is beating fast, as though I'd climbed higher, risked more. My fingers curl between the bricks. If I kept practicing, climbing, stretching--

Could I touch a star?

Would the light cling to my fingertips like the glow from fireflies? Could I paint my own stars then, across my bedroom ceiling or upon the stone in my father's circlet?

And if I captured the secret of the stars, what gifts could I give to the Eldar?

My arm stretched, pretending that my hand cups the lamp at the top of the Mindon, I can almost imagine it.

The Seedling

An alternate-universe story set in the same verse as my novella "By the Light of Roses," about how Amras met his husband Nandolin. For Vána Tuivána.

Warning: This is a slash story. It is not graphic--hopefully sweet--but readers who don't like slash should avoid this one.

- Read The Seedling

-

The Seedling

The first time I saw him, I was riding around the bounds of my father's lands. Once upon a time, I'd been led by the hand around Grandfather's menagerie, and my father had stiffly explained that the animals paced from the misery of boredom. His twitching fingers betrayed that he might like to work loose the locks and set them free.

So I paced our lands, having long ago memorized every tree and rock. What else was there to do in exile? My brothers were preoccupied with their wives and lovers, with their so-called "purposes" in life--and none wanted much to do with me besides--and so I rode in circles until I began to see the ground wearing where my horse's hooves had trod many times. My father was distracted in those days, and I dared not tempt myself with fellowship with other young Elves in the town. There was no one to free me.

Until this day.

Abruptly, I halted. He stood on the boundary of our land, staring as though awaiting an invitation to cross a threshold. He wore a dun-colored cloak that snapped in the brisk spring wind, and in his hands, he cradled a seedling. I looked at his back, his hip: In these lands, it is not uncommon to wear a bow or a sword whenever traveling out-of-doors, for the beasts here are not always allies, as they are in Valinor.

But he wore neither. I wore both.

I heeled my horse and cantered lightly towards him. It took a moment before he looked up to watch my approach, and I saw that he was large even for a Noldo, broad in the shoulder with a wide, plain face. One hand could span my entire face, I thought, but they were gentle as they cradled the seedling.

His eyes were pale golden-brown. My heart squeezed as they met mine and I stopped before him. I was a prince of the Noldor, the son of the lord of this land. But I could not convince myself to speak.

"Your earth here," he said at last, "is beautiful." So are you, I thought, but I could not bring myself to close my eyes to his face. And I should: My heart, it raced dangerously. The seedling was gnarled and half-dead. I saw that more than half of its branches had been pruned. "My tree, it will not grow in my land. But here--it might."

I dismounted. I wondered, If I told him yes, and offered him my hand, would he take it?

I don't dare!

But my quavering fingers were already stretching toward him. He shifted the seedling into one big hand and caught my hand; folded my fingers in his.

The days would pass, the tree's roots were set in the ground, and its branches brushed with the first green of spring before I realized that I'd never told him yes. But the memory--the solidity--of my hand in his: He knew.

What Becomes

Caranthir's symbolic journey to the moment that he took the oath, for Tárion.

- Read What Becomes

-

What Becomes

I.

"Like this."

Memory of youth is blurred by the years, but I remember this: Atar's hands on mine, showing me how to properly hold a hammer. I was making a gift for my mother, determined to do it on my own. Happiness: it was golden like the pendant that I sought to shape with my own hands.

Yet I perceived Atar's happiness as well. Happiness that at last he had a son eager to follow him into the forge, whose tentative hammerfalls showed that I had a hint of talent.

I remember best: gold, happiness.

His warm hands on mine.

II.

"Carnistir? Ready?."

Atar adjusted my hands and nestled my little brother into them. He squawked, and I shifted uneasily.

"Atar, I'm going to drop him."

Atar laughed. "You're not going to drop him. Relax." His warm hands rubbed my shoulders until I had no choice. I felt Atar's contentment--another healthy son born--and relief as cool and pale as water. I relaxed into that feeling and my brother stopped whimpering.

"See? It's natural for you. You will be a wonderful father someday, Carnistir." His hands still cupped my shoulders. He trusts me, I realized, with his most precious blessings.

III.

"Carnistir?"

I heard my brothers laughing and realized my eyes were squeezed shut. Violently, I shook my head and clenched my lips shut as though the light--and I could sense it, even if I couldn't see it blood red through my eyelids--would invade me if I let it. Fools! To think that we can own light! It will always be the other way around.

I could feel it thrumming in my hands with the same intimate mystery as feeling another's heartbeat. My brother's laughter was subsiding.

I won't look!

"Carnistir?"

His voice puzzled, disappointed.

I opened my eyes.

IV.

Now, I stand in a ring of torchlight, in a throng of people--my people--silent and awed. Afraid.

"Carnistir. Take it."

Curufinwë is wrapping my hands around the hilt of my sword. For a moment, time has folded upon itself and I am small upon the knee of another Curufinwë--though he would ever be called Fëanáro--and they are his warm hands. I can do this. I can hold the hammer ... and the hammer becomes the Silmaril becomes the sword, and there I am.

Standing before my father whose eyes--hands--I no longer know.

"Carnistir--are you ready?"

Evidence Of

A possibly-crazy Maglor, a decidedly weird Maedhros, and a lifetime of memories that might explain why Maglor chose the fate that he did. For Oshun.

- Read Evidence Of

-

Evidence Of

"Macalaurë."

My eyes are shut but I can see him. Maedhros. One thousand years together and I can never not see him.

"How did this happen?"

We might have been back in Tirion, still young. The way Nelyo used to laugh upon finding the remains of a party on the morning after, while I had rubbed my aching head in dismayed bewilderment. Evidence of a great life, he had called it, spreading his hands as though embracing the whole mess.

Maedhros does not do that now. Even had he hands, he would not embrace it.

"Macalaurë." Insistent now, demanding answers.

"Do not call me that." You will not let us call you Nelyo of the childhood lost or Maitimo of the beauty you no longer possess or even Nelyafinwë of the kingship you forsook, so Maedhros--that bitter name upon my tongue--do not call me that name I was given by my mother, that name I was called in love by my wife, the meaning of which is also lost.

But he ignores me: "How did this happen?"

So he had asked upon the docks of Sirion where Telvo--excuse me, Amras--had lain between us, sprawled over on his side and the rain and sea having washed his wounds to where, yes, it is as they say: He looked like he was sleeping. Amras who--we all used to complain--"took his half from the middle" and always flopped into one of us while we tried to sleep on hunting trips. Mumbled in our ears and kicked. I waited for the mumbling, but it never came, and here I am.

Still waiting.

I see Maedhros with my eyes closed. Imposing, yes, and still beautiful--but not if you knew when he was. Echoing, mocking me, for I'd asked him once: How did this happen? a great voice made frail by uncertainty in the hour following Atar's death. How did we--of the great life--become orphans?

And Nelyo--Maedhros--had kicked a shower of dirt down the hill. Because it did! There is no reason! It is like those rocks-it tumbles where it will!

No, I'd always liked music where the score always led somewhere and there were rarely surprises.

Now he haunts me with it: "How did this happen?" Gesturing at the sand, I see, with his right hand. Or--where his right hand should be. In practice, he uses the left, but practice shall never erase instinct.

I squeeze my eyes shut tighter, but still I see. I would dig my eyes from my face, but still I'd see.

"Macalaurë?"

Footprints meandering down the sand. One set--no two! Three! Where we'd let them go. He wants to walk and erase them, as though erasing evidence of our loss will bring those lost back to us. I wait with eyes tightly shut.

But it never works. I open my eyes. His footprints now lie in their stead.

"How did this happen?"

And I am alone.

Spent on Joy

For Jenni, the unlikely alternate-universe pairing of Fingon and Caranthir.

Warning: This is a slash story. Not graphic, but if you don't care for slash, please skip this one.

- Read Spent on Joy

-

Spent on Joy

I. Tirion

I had the most unlikely ally in my cousin Carnistir, whom few seemed to like and fewer to understand. But we would meet at the city gates and he would warn me of things.

"Your father," he might say, "has just had tremendous row with my father. I suggest that you tidy your room."

Or: "Your mother is arranging supper with the girl with the big teeth, so you and Turukáno might want to go to Alqualondë for a week."

How he learned these things, I would never know. Carnistir was very good at sneaking and hiding, at melting into shadows and catching the faintest thread of conversation. Daily, I would descend to the gates and mill among the throng, where the meeting of two cousins would likely not be noticed, much less regarded as suspicious.

I approached, always, with the thought that he would not be there. With the muscles in my chest held tight as though to buoy my heart, which felt like it plunked heavy as stone next to my stomach when I failed to find his dark head among the crowd. I found myself wondering why his friendship meant so much.

To both of us, apparently.

II. Mithrim

We met at the intersection of Ours and Theirs. Too wearied to devise names, this was what we called the two lands that met at the tip of the lake, in sight of both camps.

It was not planned. I wandered, he wandered--there we were, between Ours and Theirs. Standing and facing each other as though the intervening centuries of discord had not existed. "Findekáno," he said without greeting, scraping his toe in the dirt, "Nelyo is gone."

In life, we take actions, my father often said. I imagined in that moment the actions that I might take. The strange thought came to catch my cousin's face in my hands and to kiss each of his eyes. I wondered at the feel of his eyelashes fluttering against my lips. Or the heat of his flushed cheeks against my palm.

For a moment, I thought hopefully, he might forget that Nelyo was gone.

But only for a moment. Then I would return to Ours and he would return to Theirs, and we would resume our private heartache, each staring at the imagined other across the water. This reconciliation--however brief--need never happen again.

Or maybe--there was another way?

III. Thargelion

When my father died, I rode forth from Hithlum. No one stopped me. They believed that I sought my brother and sister, long disappeared but suddenly desired at this time of terrible grief. Or perhaps solitude: my thoughts erased in a roar of wind and hoofbeats.

None would have believed that I sought the so-called Dark Son of Fëanor.

Yet there he was, loping towards me, dismounting before I had even stopped, and the childish words nearly formed on my lips: "What warnings do you bring today?"

But we'd long ago realized the futility of warnings here. His eyes spoke of them, and I felt a shiver of dread. His lips parted, and perhaps he would have spoken. Perhaps he would have warned me. Or perhaps he knew that I would seek my father's murderer, no matter the cost.

As he had done.

Or perhaps he knew that fate would be what it was, and he could not change it. Not with fiery words or bright swords.

He caught my face in his hands. He kissed my eyes. Then my mouth.

Or perhaps he believed-as I did-that this last time we met: It should be spent on joy.

Comments

The Silmarillion Writers' Guild is more than just an archive--we are a community! If you enjoy a fanwork or enjoy a creator's work, please consider letting them know in a comment.