Who Gets to Say? Canon and Authority by Dawn Walls-Thumma

Posted on 25 March 2023; updated on 25 March 2023

This article is part of the newsletter column Cultus Dispatches.

Fanworks always come with the issue of canon.1 After all, the creator is using someone else's work as a foundation for their own. What of that original work is the creator obligated to keep and where can they deviate? Given its extensive and complex canon and the value many fans place on mastering its details, Tolkien fandom has always been concerned with matters of canon, and fans have expended significant effort to collect canon details, correct what they perceive as misconceptions, and advocate for their particular stance on a canon question.

Of the wealth of details Tolkien gave about his world, few are truly settled canon because of the nature of his works and the number of adaptations made based on them. Most Tolkien fanfiction writers have considered questions around this: whether "canon" is Tolkien's final word or the published story or the most developed ideas (or just what a fan personally prefers), how Christopher Tolkien's editorial choices factor in, where "canon" shades into "interpretation," and of course where the films and other adaptations fit in to each fan's personal vision.

These issues are questions of authority. Who gets to say what is canon and what is not? This month, I will look at how Tolkien fanfiction authors assign the authority to determine what is canon and what is not.

Canon, Capitalism, and Tradition

Typically, Western culture—being capitalistic—locates the authority to define canon with the original creator and rights holders. As the only people with the authority to say what definitively happens in a story, those individuals also retain the ability to profit on those creations. This is the byzantine tangle of laws that we know as copyright: Who gets to profit, yes, but also, who gets to say?

For many of us, this is the only system we've ever known, making it easy to assume it is the only approach possible to take. Of course, we might say, the author of a novel gets to decide what happens to her characters! Of course, many of us would add, the people investing money to have a film made based on a book would have the authority to change the plot or characters in order to increase the likelihood of that film becoming profitable. We might prefer that the film studio consult with the author as part of this process, but even if this didn't happen, few of us would find it a travesty. An investment of money extends authority over a work and therefore its canon.

This is not, however, the only approach. Consider mythology, folklore, and other examples of predominantly oral storytelling. As a middle-grades humanities teacher, I am often my students' first serious introduction to mythology, and their biggest struggle tends to be when there is no single "correct" version of a story. How can both Hathor and Isis be Horus's mom? they ask. Is Hermes a wanton trickster-thief or the prudent herald of the gods? Both are true—how?? No matter that they understand these stories were told across hundreds or thousands of years and no matter how many times I use the telephone-game analogy (and how well they understand it), and no matter how many discussions we have about how these stories were shaped and changed to the storyteller's purpose in that moment, they seek that single, inviolate, "right" version of the story because they were raised in a Western culture where stories are presented in this way.

Most of us are no better. How many of us have said something like, "In the real version of the story, the Galadhrim do not show up at Helm's Deep" or "In the actual book, Fëanor is not nearly that nice," as though those film and fanfic versions of the story are less "real" or "actual" than another version of the story that we view as more authoritative? From this idea that some people have more authority to determine a "correct" version than others comes the concept of canon, baseline assumptions about a text that most fans accept as correct.

A Fan Studies View of Canon

Most fanfiction scholarship relocates the authority to shape, change, and completely rewrite a story from the original creator and those with an economic stake in the original work (publishers, production companies, television networks, etc.) to fanworks creators. In other words, many fan studies scholars would say, fans—not just original creators and rights holders—regard themselves as having equal or more authority to change the canon to shape their purpose, much as oral storytellers look out at their audience, consider what they hope the purpose of their story will be, and shape the telling accordingly.

Fan studies scholars can certainly find support for this idea. In the 2013 essay collection Fic: Why Fanfiction Is Taking over the World, Anne Jamison describes the total handover of canon to fans in the Twilight fandom, where authors sometimes wrote with only the barest familiarity with the source material and a complete disregard for what the plot and characterizations presented in the books and films:

The Twilight saga stopped functioning as source per se and began functioning as one massive erotic romance prompt. A template. It provided a basic structure, some basic characterizations, and relationship and plot trajectories, but increasingly these elements appeared vampire- and glitter-free. … Sometimes only the vaguest parallels were retained. … Twilight had been eclipsed. There was fic for fic. Readers and writers alike began to forget where canon stopped, where fanon began. Twific had taken over its own world.2

Jamison recounts how fan writers would write original romance stories, then change the names to those of Twilight characters, seeking the massive audience for fanfiction early in that fandom's history. Obviously, this is an extreme example, but in fan studies scholarship, there is a tendency to assume that readers and fans are gleefully willing to shoulder aside the original creator and assume authority over how canon is defined. While fans' love for the source material may receive a nod, rarely is it acknowledged that fanfiction writers perceive that traditional authorities over their beloved texts do retain some of that authority, even in the world of fanworks. Fanworks creators, instead, are depicted as a freewheeling lot who, on a whim, alter the canon with a dabble of their fingers across the keys for reasons both profound and frivolous—but always with a mind to shape the canon toward their own experiences and preferences.

The appeal is obvious. It is democratic; it puts the meaning (and therefore the power) of a culture's most important stories back upon the people; it seems a big "F you" to rights holders perceived as profiteers at the expense of fans and even original creators; it elevates the stories of people whom pop culture has marginalized and maligned.

But in many fandoms, including the Tolkien fandom, the shift of authority from the original creator onto fans is not that simple. Here, I'm going to begin to draw on data from the Tolkien Fanfiction Survey, run in 2015 and 2020, the latter in collaboration with Maria K. Alberto. This survey included writers and readers of Tolkien-based fanfiction. We collected demographic information and presented a variety of statements about practices and beliefs about fanfiction, to which participants could choose Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, Strongly Disagree, or No Opinion/Not Sure. Unless otherwise stated, results discussed in this article are from the 2020 survey, for which there were 746 participants, 496 of whom were fanfiction authors.

On Whose Authority??

Earlier, I stated that canon is challenging to define in the Tolkien fandom if only because of the number of people who have exerted some authority over the texts.

- Tolkien himself, of course, is the original creator, but as many of his works are posthumously published, we cannot discuss The Silmarillion and related works without bringing in

- Christopher Tolkien, who has had the greatest influence on how we see his father's unpublished writings, most of them related to the "Silmarillion" materials. The construction of the published Silmarillion required Christopher to sometimes choose from several versions of a text and, in places where the text was incomplete, write entire sections from whole cloth.

- Filmmakers, showmakers, and other creators of adaptations are often dismissed by Tolkien fans as having any authority over what they acknowledge as canon (after all, Tolkien fanfiction fandom remains a largely book-based fandom), but for many fans, an adaptation is their first exposure to Tolkien, and the ubiquity of images associated with the films and other adaptations can influence how even the most bookish fan "sees" Middle-earth. (For example, I've heard fans make the convincing case that the whiteness of Middle-earth is less Tolkien and more Jackson.)

- Tolkien scholars also enter into Tolkien fandom in a way that scholars do not in other fandoms. There are, after all, entire courses on Tolkien studies on offer at many colleges and universities, though Tolkien scholars tend to hang out less in the lofty echelons of the ivory tower and more on Twitter, blogs, and the same places as Tolkien fans more generally. Furthermore, most major Tolkien studies journals are open-source, making Tolkien scholarship highly accessible to

- Tolkien fans, a group that has produced a wealth of resources and writing about Tolkien's world outside the bounds of traditional scholarship. If you've ever used a fan-written article or a wiki to jumpstart your knowledge of a character, setting, or event—not to mention the influence of fan art, fanfiction, fansites, and so on—you can appreciate how fan-created resources shape what we know as canon.

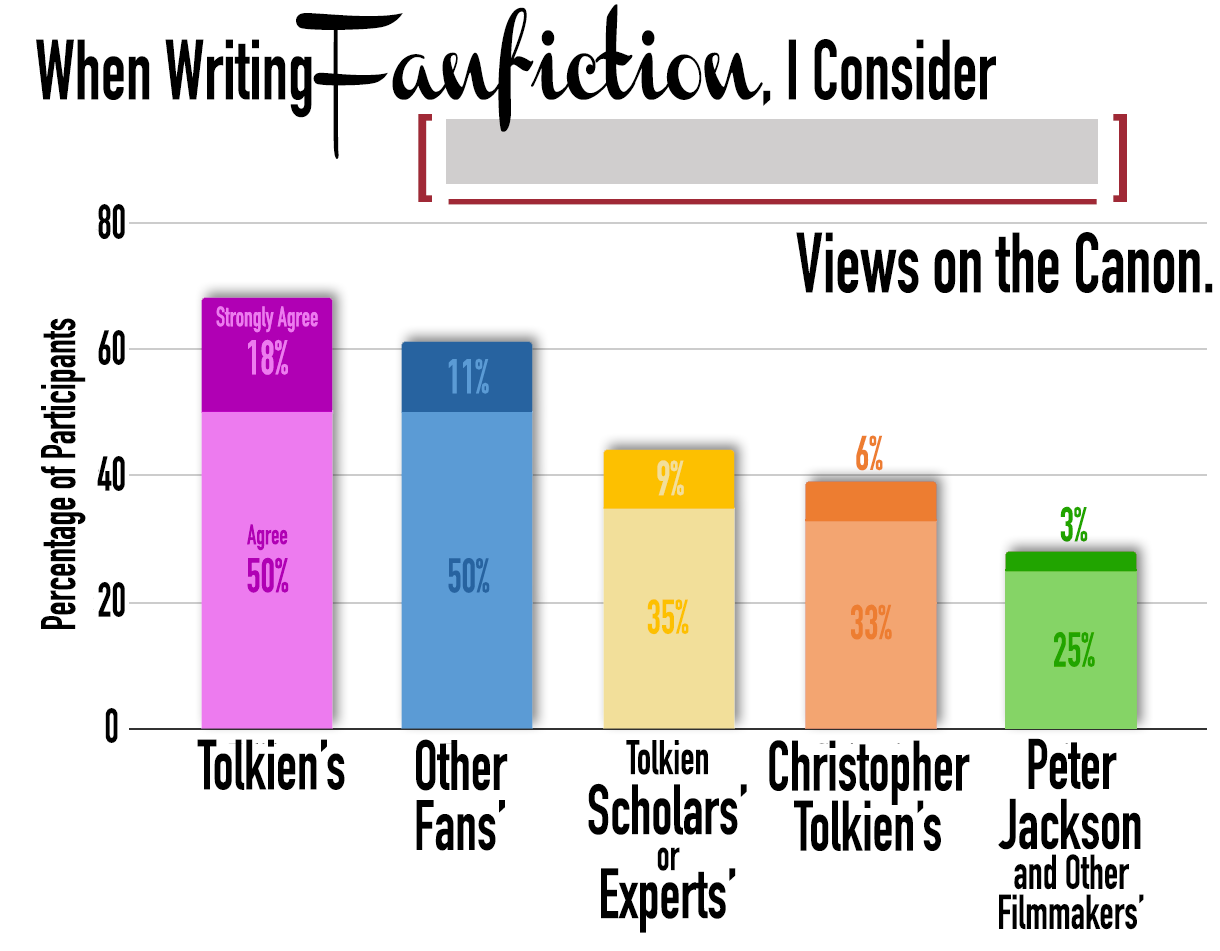

The 2020 survey included five Likert-style items phrased as, "When writing fanfiction, I consider ____'s views on the canon," where the blank is filled in by the various persons who have authority over the texts in various contexts: Tolkien, other fans, Tolkien scholars and experts, Christopher Tolkien, and Peter Jackson and other filmmakers. The results for all authors are in the graph below.

In these data, we see that the tendency to view fans on a binary—either they are rabid "canatics" who give Tolkien's word an almost religious reverence or they're carefree fanficcers who will brush aside Tolkien's most cherished ideas if it means they get the right characters in bed together—is overly simple. Tolkien fans occupy both views of authority. Two-thirds of them consider Tolkien's views—a not-insignificant majority—but nearly as many value their fellow fans' views nearly as much.

And none of the possible authorities Maria and I asked about received a negligible amount of consideration. Even Peter Jackson and his team—the least considered of the five—influenced the views on canon of more than a quarter of fans. (And, as we'll see, the filmmakers' influence pervades discussions of canon and authority even when it doesn't seem like it should.)

Canon and authority is a massive topic. I could write a book on it using the data I've gathered across two Tolkien Fanfiction Surveys now—but I won't, at least not now. In order to whittle the topic down to a manageable size, I've considered three groups of interest, whom I call the Tolkien dissidents, the Jacksonites, and the bookverse authors based on where they place authority over canon.

The Tolkien Dissidents

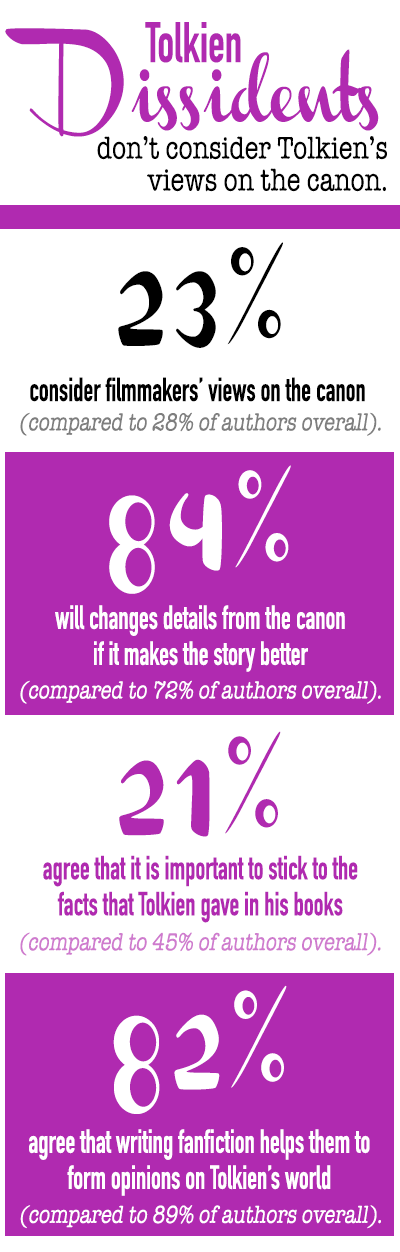

I was curious about the 23% of authors who disagreed or strongly disagreed3 with the statement, "When writing fanfiction I consider Tolkien's views on the canon," a group I will call the Tolkien dissidents. I wondered if they considered other forms of authority more often or if they viewed fanfiction as a vehicle for forming their own interpretations of the canon.

I was curious about the 23% of authors who disagreed or strongly disagreed3 with the statement, "When writing fanfiction I consider Tolkien's views on the canon," a group I will call the Tolkien dissidents. I wondered if they considered other forms of authority more often or if they viewed fanfiction as a vehicle for forming their own interpretations of the canon.

The short answer to both is no.

On the other four "authority" questions above, the Tolkien dissidents also disagreed that they considered other fans'/scholars'/Christopher Tolkien's/Peter Jackson's views on the canon more often than did participants overall. In other words, it is not like they are, as a group, supplanting Tolkien's authority with someone else's—not even other fans', as might be predicted by the fan studies' theory that fanfiction shifts authority from original creators and rights holders onto fans. Nor are they filmverse fans who have replaced Tolkien's authority with Jackson's. They just don't seem to put much stock in outsiders' views on the canon at all.

So what is going on with these authors who seem to shrug away the very idea of an authority over canon? I considered that the Tolkien dissidents were the sort of authors who use fanfiction to construct their own understanding of Tolkien's world, so-called "authorities" be damned—but they actually agree less often with the statement that "[w]riting fanfiction helps me to form my own opinions about Tolkien's world" than authors overall.

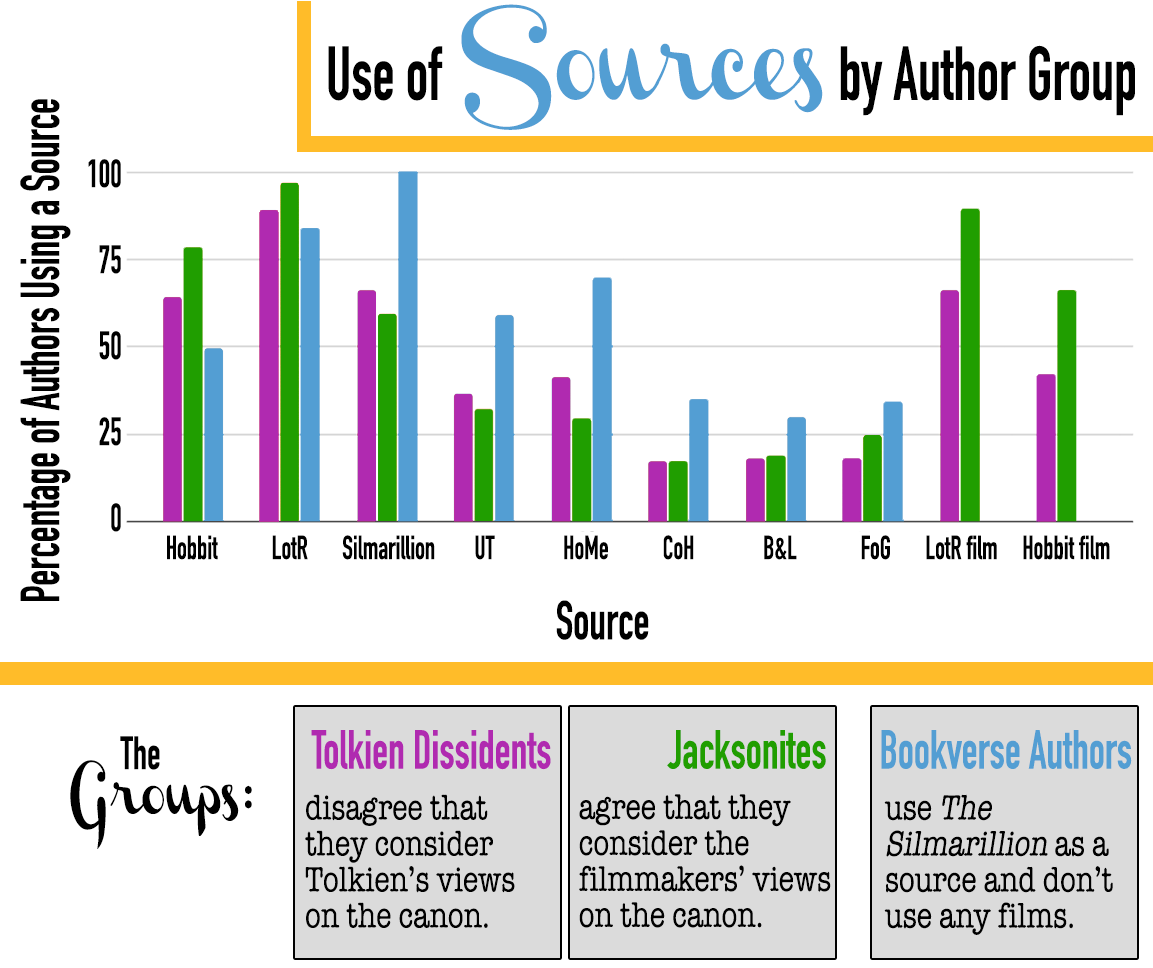

We do see a notable difference between the Tolkien dissidents and authors overall on a pair of survey items that get at the practice of using canon in fanfiction. Tolkien dissidents are more comfortable with changing details from the canon if they believe it will improve the story, and they are less likely to care about adhering to the facts Tolkien gave in his books. While using The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings (LotR) books about as frequently as other authors, Tolkien dissidents are less likely to use the books for which there is no film and more likely to use the two Jackson trilogies. (You can see source data, along with data collected for the other two groups I studied, in the "Use of Sources by Author Group" graph below.)

What's going on with this group? Their higher use of the films might suggest they are filmverse fans of the bogeyman type invoked in the early-mid 2000s: those whose reverence for the films would overpower any reverence for Tolkien, allowing the films to overtake the books as canon. But they clearly don't have much reverence for Jackson and his team.

What I think is happening here is exactly what Amy Sturgis predicted would happen in her 2004 article "Make Mine Movieverse": For this group of fans, the films have normalized deviation from the books and give fanwriters similar leeway to pursue their own creative visions in their stories.4 The release of the films did not produce a simple shifting of authority over canon from Tolkien to Jackson. Rather, by presenting a version of Middle-earth that, in some instances (some of them very prominent), broke with Tolkien's canon and yet still managed to feel like Middle-earth, fans were shown that strict adherence to the canon wasn't a necessary requirement to produce transformative works that stayed true to the emotional, stylistic, and thematic feel of Middle-earth. I suspect the Tolkien dissidents exemplify a group of fans that have internalized this approach.

The Jacksonites

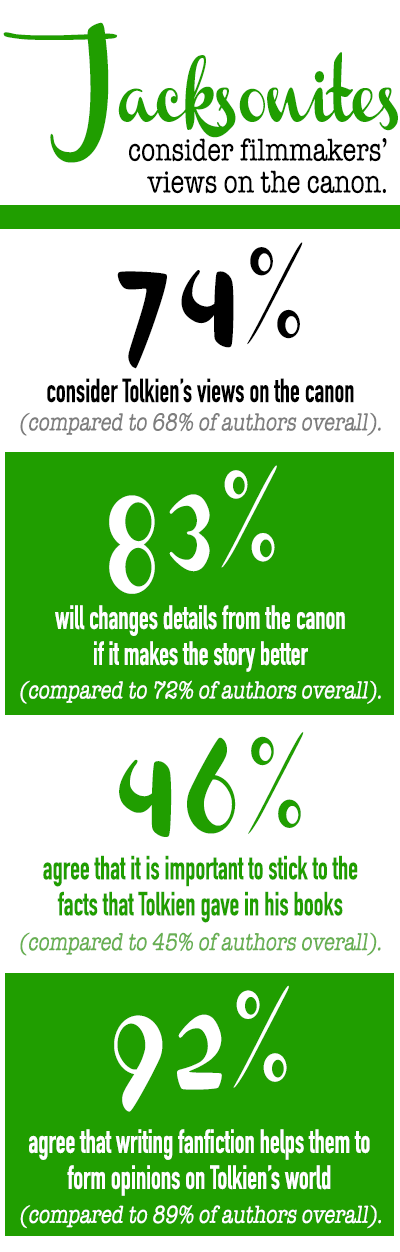

Another subgroup that interested me were the 28% of authors who agreed that they "consider Peter Jackson and other filmmakers' views on the canon," a group I call the Jacksonites. While the smallest of the five groups, they still are not small: This is more than one in four authors willing to acknowledge that they take Jackson as canon. (I use emphasis because I believe many more accept details from the film trilogies as canon without necessarily realizing it. But the Jacksonites are conscious of this choice.)

Another subgroup that interested me were the 28% of authors who agreed that they "consider Peter Jackson and other filmmakers' views on the canon," a group I call the Jacksonites. While the smallest of the five groups, they still are not small: This is more than one in four authors willing to acknowledge that they take Jackson as canon. (I use emphasis because I believe many more accept details from the film trilogies as canon without necessarily realizing it. But the Jacksonites are conscious of this choice.)

As I've noted many times before, Tolkien fanfiction fandom is largely a book fandom, though there are certainly communities within the fandom that are more media-oriented. (The enormously popular Bagginshield ship is one example.) However, while many fans' first interest in Tolkien comes from the films—I am one such fan—those who write fanfiction almost always turn to the books before long. In both the 2015 and 2020 surveys, less than 1% of fans used only the films for their fanfiction.

Yet, as I noted above, the films have an undeniable influence, even if only in how many of us "see" Middle-earth in our own imaginations, often without even realizing that Middle-earth can look like something other than New Zealand populated by attractive white people. The early-mid 2000s campaigns against blue-eyed Frodos and blond-haired Legolases can be seen as proxy wars in a broader insistence that fans reject the vision of Jackson's team in favor of the books as the predominant canon authority.5

So what do these fans look like who do openly accept Jackson and his team as authorities on the canon? Some of the data are unsurprising. Jacksonites are far more likely to have begun writing due to the films (75% agreed compared to 45% of authors overall) and to agree that the films encouraged them to write fanfiction (90% compared to 57% overall). They identify the two Jackson trilogies as sources for their fanfiction more frequently than do authors overall.

They are bookverse fans, but the shape of that looks a little different than it does among fanfiction writers as a whole. (See the "Use of Sources by Author Group" graph below for a visual representation of these data.) They are more likely to use the LotR and Hobbit books than fanfiction writers overall and less likely to use the works posthumously published by Christopher Tolkien, such as The Silmarillion. There could be a couple of different explanations for this. As fans who more heavily regard the films, they might turn to the books that specifically bolster the film canon. Another explanation could be that, as fans largely introduced to Tolkien by the films, they might have just begun to explore the books and haven't yet read (or aren't comfortable enough) with books like The Silmarillion that are typically read after a fan has worked through The Hobbit and LotR. (Survey data does show that, the longer authors remain in the Tolkien fandom, the more books they add to their writing repertoire.)

Like the Tolkien dissidents, the Jacksonites are using the films more heavily in their fanfiction than authors overall, but how they use the various canon texts—namely in how they perceive authority around canon—looks very different than the Tolkien dissidents. Where the Tolkien dissidents rejected all forms of authority assessed in the survey at higher levels than authors overall, the Jacksonites are the opposite: They are more likely to agree that they accept Tolkien's/other fans'/scholars'/Christopher Tolkien's views as canon, often at much higher levels than authors overall.

Where the Tolkien dissidents seemed to take the films as permission to pursue their own creative aims absent any authority (as Sturgis predicted), the Jacksonites use the coexistence of the books and films as their canon as reason to remain open to details and interpretations from a variety of authorities. Their willingness to alter the canon if they believe it will improve their story is on par with the Tolkien dissidents (83% compared to 84% for the Tolkien dissents and 72% of authors overall), but they are just about equally interested in staying true to the facts Tolkien gives in his books (45% of Jacksonites agree compared to 46% overall) and, as noted above, revere Tolkien's views above authors overall. This shows a willingness to manipulate the canon coupled with a reverence for that same canon.

Earlier I noted that fan studies scholars, intentionally or not, sometimes create the impression of a binary among fans, where fans either cling to the word of sanctioned authorities or abandon all fidelity to the canon to do what they want. I have long made the argument that fans' responses to authority are complicated, and the Jacksonites are a case in point: a group of fans who occupy seemingly opposing stances yet do so with all of the comfort of a traditional storyteller where truth cannot be confined to a binary and canon morphs based on the audience before them and the story they need to tell.

The Bookverse Authors

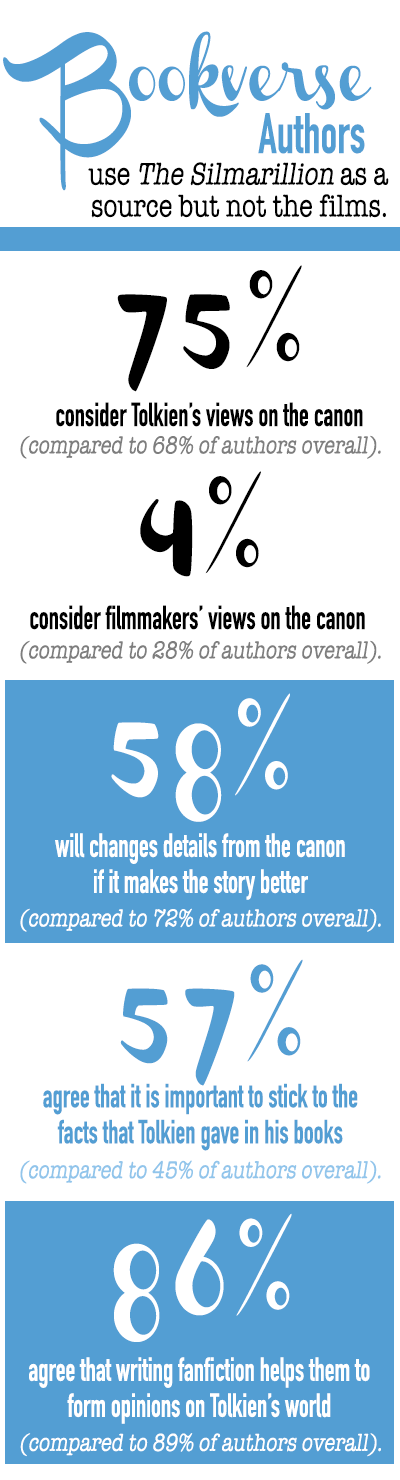

If Tolkien fanfiction fandom is a book fandom, it makes sense to consider how these fans—those who don't use (or at least don't acknowledge using) the films as sources—regard authority in their fanfiction. We've seen two groups—those who reject Tolkien's views on the canon and those who embrace the Jackson team's authority—that include filmverse fans to a much greater extent than the average Tolkien fanfiction writer. Data in this section, in comparison, includes authors who use The Silmarillion as a source but neither of the film trilogies, a group I've termed the bookverse authors.

If Tolkien fanfiction fandom is a book fandom, it makes sense to consider how these fans—those who don't use (or at least don't acknowledge using) the films as sources—regard authority in their fanfiction. We've seen two groups—those who reject Tolkien's views on the canon and those who embrace the Jackson team's authority—that include filmverse fans to a much greater extent than the average Tolkien fanfiction writer. Data in this section, in comparison, includes authors who use The Silmarillion as a source but neither of the film trilogies, a group I've termed the bookverse authors.

Whom do bookverse writers consider as authorities able to decide what constitutes canon? Perhaps not surprisingly, they consider Tolkien's views on canon more than authors overall, with 75% agreeing on that survey item compared to 68%. They consider the views of other fans slightly less often (57% compared to 61%), and they value Christopher Tolkien's views on the canon more than fanfiction writers do overall (44% compared to 38%) but still at levels that I find surprisingly low, given that Christopher Tolkien selected and edited much of the material they are using as sources for their fanfiction.

But the most startling difference in how this group defines canon occurs when considering the views of Peter Jackson's team and other filmmakers. This group really does not put a lot of stock into those views: only 4% considered them compared with 28% of fans overall. This isn't exactly surprising—after all, these authors do not use either of the Jackson trilogies as sources for their fanfiction—but their rejection of Jackson and the other filmmakers almost becomes the defining trait of this group, even more so than their acceptance of Tolkien's views. (After all, 25% of them didn't agree that they considered Tolkien's views on the canon!)

These writers tend to gravitate toward more obscure books and away from the more typical texts. They are less likely to use The Hobbit and LotR books as sources for their fanfiction than authors overall but were more likely to identify posthumous texts as sources for their fanfiction. In some cases, their use of these books was significantly higher than in the fandom overall. For example, while only 48% of authors used the History of Middle-earth series, 70% of authors in the bookverse group did. (See the "Use of Sources by Author Group" graph below for a more detailed breakdown.)

Both the Tolkien dissidents and Jacksonites exhibited some willingness to deviate from the canon. The bookverse authors, in contrast, place a higher value on adhering to the details from the books. For example, while 72% of authors were willing to deviate from the canon if they felt it improved the story, only 58% of this group agreed that they did this. On the survey item about the importance of "stick[ing] to the facts that Tolkien gave in his books," 57% agreed compared with 45% of authors overall. While the Tolkien dissidents and Jacksonites suggest that use of the films as canon sources either gives permission to deviate from the books or to consider a simultaneous multitude of sources as canon, the bookverse authors' data suggest that working entirely within the book canon encourages adherence to those books. It may be that bookverse authors are less likely to view their purpose in making creative choices that they believe improve the story (even when those choices break with canon). Instead, their task is to work with the materials they have—the canon—to tell the best story they can within those delimited bounds.

Conclusions

As of this article, I've been the lead writer on the Cultus Dispatches column for a year now, a year that included the not-insignificant event that was the debut of the Rings of Power television series. Within that historical context, I have often found myself teasing out the influence of the six Jackson films on the Tolkien fanfiction fandom, both to prognosticate and reassure (often myself!) that the new television series will not upend the fandom as we know it and turn it into yet another media fandom.

When I set out to write about authority and canon this month, I did not set out to focus again on the films—yet here we are. As I've said more times than I can count over the last year, the Tolkien fanfiction fandom is a primarily book fandom; media products tend to drive fans to the books rather than bifurcating the fandom into separate book and media fandoms (e.g., the Sherlockian and Sherlock fandoms) or supplanting the book fandom with a media fandom as bookverse fans often fear. Yet I cannot deny that the films—colossal and unavoidable as they are—exert a gravitational pull upon the fandom as a whole, much like an enormous moon, bright in the sky and pulling at the tides. Yes, the films are but satellites in the big picture of the fandom, but one sometimes can't help but feel that everything in sight is touched by them, their gibbous light reaching into even the most stubbornly shadowed corners.

As I sought to answer the question of how Tolkien fanfiction writers define authority over canon, the films were a consistent predictor of how fanwriters negotiate authority in their work. The tl;dr of this set of data would be that fans who use the films as canon will change that canon more readily in their stories than bookverse authors will. Yet that's an oversimplification that, much like the false binary of fans who embrace authority and those who flout it, robs us of the complexity behind how many fans navigate authority and canon. The group I've termed the Tolkien dissidents seem to use the films to wave away any obligation to adhere to what authorities of any stripe would term their canon. The Jacksonites, on the other hand—the group that most readily embraces the canon put forth by Jackson's creative team—couple their acceptance of the films with a reverence for Tolkien's word and have the most complicated relationship with canon and authority of the three groups I discussed. They truly seem to approximate the traditional storyteller, who manages to be comfortable with many versions of history, fact, and truth, prioritizing audience and story over canon. Even the bookverse fans—who might seem the simplest group of all—reject the traditional authorities of J.R.R. and Christopher Tolkien at startlingly high rates, showing that even their seeming devotion to the books is more complicated than it seems.

All of this leads me to again proclaim the complexity of all of this: canon, authority, storytelling. I'm a writer myself. I know that the way I negotiate the choices I make in my Tolkien-based stories does not adhere to a single approach. Sometimes I may prioritize the canon; other times I might prioritize the story. The details that I accept or reject as canon depends on my purpose and may very well change from story to story. The authors behind the data in the Tolkien Fan Fiction Survey are likely much the same, acting foremost out of a love for an imaginary world and the joy they feel to create stories about that world less than adherence to any politics or purpose seen as motivating their fanfiction or how they define canon.

Works Cited

- If you're used to the terminology used in literature and not fan studies, you should know that, when referring to fanworks (or transformative works, as they're sometimes called), canon is not a culture's collective foundational works but the texts or details within a particular fandom that are accepted by most fans as correct.

- Anne Jamison, Fic: Why Fanfiction Is Taking Over the World (Dallas: BenBella Books, 2013), 181.

- Going forward, to keep this article more readable, when I say "agree," I mean that the participant chose Agree or Strongly Agree. When I say "disagree," I mean that they chose Disagree or Strongly Disagree.

- Amy Sturgis, "'Make Mine Movieverse': How the Tolkien Fan Fiction Community Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Peter Jackson” in Tolkien on Film: Essays on Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings, ed. Janet Brennan Croft (Altadena, CA: Mythopoeic Press, 2004), 286.

- It's important to note that the early-mid 2000s objections to the appearance of characters in the Jackson films—and how willingly fans assumed these appearances to be canonical—almost never focused on diversifying Middle-earth or questioning its whiteness. These were almost always bookverse-versus-movieverse debates, with pages of quotes produced and minutely analyzed to show that "Tolkien never intended" Legolas to be blond, for example. The purpose of these objections was usually to encourage fanworks creators to embrace the book canon (or a particular interpretation of the book canon, since Tolkien was rarely direct in describing his characters' appearances) over the "easy out" of describing the characters as they appear in the films.

Rather, by presenting a…

Rather, by presenting a version of Middle-earth that, in some instances (some of them very prominent), broke with Tolkien's canon and yet still managed to feel like Middle-earth, fans were shown that strict adherence to the canon wasn't a necessary requirement to produce transformative works that stayed true to the emotional, stylistic, and thematic feel of Middle-earth. I suspect the Tolkien dissidents exemplify a group of fans that have internalized this approach.

AHA! This is (at least partly) me, but I never thought to articulate it like that.

Really thought-provoking read. Thank you.

When I read Amy Sturgis's…

When I read Amy Sturgis's article, this was a big ah-ha moment for me too, not so much because I felt it applied to me but because it explained some of the fandom cultural changes I observed (as a fan who began participating during the LotR film trilogy release) and in my data. Clearly the films made an impression, but this is belied by the fact that less than 1% of authors in the survey were true filmverse authors, writing only based on the books. So what was going on? It makes perfect sense to me, given how many bookverse fans nonetheless love the LotR films and feel that Jackson et al really captured something essentially "Middle-earth," that the films would become an exemplar of how being "true to Tolkien" doesn't require perfect adherence to factual details.

Thanks for reading, especially for commenting, and I'm glad you enjoyed the article!

Canon thoughts

As primarily a reader (with just the one published Tolkien fanwork to my name) and coming from the pre-film days, I started with a bookverse "only what JRR Tolkien wrote" view of canon, not really realising how much of the Silmarillion, Lost Tales and Histories were Christopher. The film changes (Arwen-Glorfindel, no Scouring of the Shire, Tauriel etc) were anathema. While works written by both Tolkiens are still canon in my view - even when they clash or contradict, fanworks and fanwork authors (and probably scholars) are contributing something special, and are what make this fandom interesting and quite wonderful. Their views and ideas are not canon.... but they can be canon-adjacent. And I'm fine with that.

I came to Tolkien via the…

I came to Tolkien via the LotR films, but I was only ever really in the fandom for the Silm, so I was very similar in my early views on canon. In the early-mid 2000s, understanding of the construction of the Silm was less understood by the average fan than today AND I was a new Tolkien fan and grappling with a lot of canon as it was, so "the Silm is canon, full stop," was a pretty natural perspective for me to take. So I'd say things like, "It's totally okay to write Maedhros/Fingon [and I did myself beginning in 2005], but I don't think it's canon," and in fact would have classed it as AU (and probably did, with those early Mae/Fin stories). Today ...? It's a much squishier question for me. I always assumed that that the more I learned about Tolkien, the more solid my understanding of what is/is not canon would become, but the opposite has happened. The more I learn about Tolkien, the more I understand that what we have been given as "canon" is just where the texts happened to stop in their written state, even negating Christopher's mediations of those writings, and it makes it really hard, given that, to accept anything as incontrovertible fact. I mean, JRRT was preparing to change the actual solar system late in his writings, so who knows what a published Silm from JRRT would have looked like?

ETA that I got so involved in this response that I forgot to say thank you for reading and commenting! <3

Interesting set of data and…

Interesting set of data and great analysis! Fascinated by the 'Tolkien Dissidents' category especially. I admit I read this out of order because I was impatient to get to the data, but it kind of made it more interesting. As I was reading that section I was mentally sputtering over how someone could possibly be writing Tolkien fic and not strongly agreeing that they consider Tolkien's view of canon... but then going back and reading the section on Capitalism and Tradition, as someone who made an academic study of mythology and oral tradition and loves the concept of, shall we say, diffused cultural authority, I felt very called out 😁 (in a good way). The article has certainly given me some food for thought.

I get that! My Master's…

I get that! My Master's thesis was on the use of oral formulas as stylistic devices to create a sense of nostalgia in Beowulf, so intrigue and admiration for "diffuse cultural authority"?? ... yep! :) But I also find the Tolkien Dissident category, of the three, to be the one I have the hardest time wrapping my brain around.

I really want to dig into those responses some more. There are questions on the survey about treating fanfic as serious art, for example, and I'd be interested to know how this group compares to participants overall on those types of questions. Are they assembling a variety of raw materials to make the best adaptation they can make? Or ...?

Thanks for reading and especially for commenting!

Very interesting, Dawn! I…

Very interesting, Dawn!

I have sometimes thought that the way fandom uses canon is a bit like much earlier uses of the canon concept in history: the set of laws that are valid in your world or the set of religious texts that are accepted by your community as containing the genuine revelation...

The idea of copyright may be linked in some fashion to capitalism, but one of the underlying ideas is to make the author of a work be not entirely at the mercy of the publisher or dependent on patronage, as they had been previously, so it would be perfectly possible to have no-holds-barred capitalism without authorial copyright at all, it seems to me, and in some areas we do seem to see developments that tend that way.

If you are a book 'verse fan, I think you can be "canon-oriented" in at least two ways: you can think there is only one canonical reading and that you know what it is or you can be (in Silm fandom, particularly) someone that enjoys exploring the different version of book canon, picking and choosing and sometimes pushing them to their limits. A bit like gaming the system: you could take pride in avoiding explicit canon breaches, because there are so many options to explore within it!

I think that, in the Silm fandom particularly, but also more generally in Tolkien fandom, there has been some impact through the increasing availability of material from HoME and other less accessible sources through wikis, extending access to this type of canonical material and making it more "mainstream". Users don't always think of this type of access as mediated and, if so, they would not be thinking of it as filtered by "experts", even as they are using Tolkien Gateway, etc. as a secondary canonical source.

I will admit that it's taken…

I will admit that it's taken me a while to reply (sorry!) because I've been turning over your comment on capitalism because ... I'm not really sure we disagree? Copyright establishes ownership over a creative work; it makes it private property and therefore able to be profited from. I agree that it protects creators—I am not opposed to copyright for this reason—but it does mean that creative work is not collectively owned and able to be used equally by everyone. This seems a pretty radical concept in the larger history of art/literature and one that doesn't seem to have an intent beyond ensuring that money for creations gets funneled to the right person ("right" in the legal sense, not necessarily the ethical sense) and therefore seems pretty solidly part of a system where art/literature becomes a commodity. Is it the only system possible within a capitalist system? Surely not. But I'm unable to divorce it from capitalism. If I'm missing your point, please let me know!

I agree! The "genuine revelation" made me laugh because I remember canon-oriented conflicts early in my fannish experience often feeling like religious debates. Whether Balrogs had wings approached the intensity of determining the correct date of Easter and, to an outsider, likely seemed equally pointless. (But to "insiders" ... whoa, the wings-or-lack-thereof meant so much more because they were often a proxy for larger cultural issues.)

I agree, and I think this is huge. I remember being genuinely shocked when ford_of_bruinen first pointed out to me that Guy Kay was hired by Christopher Tolkien to help him write sections of The Silmarillion. There was definitely this sense that the published Silmarillion was somehow the best of Tolkien's final word; the idea that there were still gaps and inconsistencies that needed to be filled ... *mind blown* Now it seems silly that I wouldn't have known that. And of course diving into the HoMe itself, I grew increasingly aware that I was reading selections made by Christopher. I trust Christopher's judgment above all others ... but it was still a judgment, a selection, with all that entails. It wasn't truly "canon."

Then of course those sources are further selected and commented upon (however slightly) by people making resources about Tolkien. I am never more aware of this than when I am working on a character biography and trying to decide which quotes to include, where to place the emphasis, the focus to take. It definitely crosses my mind that I'm shaping how people who will use my work as a secondary canonical source (to borrow your term!) see a character and perhaps use that character in their own work. Which brings us to fanon and ...

Now I kind of want to make a big diagram of all of this. Surely I have better things to do with my time! (But if you see the diagram at some point later today, know the devil on my shoulder won out ...)

Thanks for reading and for the always thoughtful comment. :)

Follow-up on the point about capitalism

I'm afraid I wasn't making clear enough where I was coming from, there!

I wasn't disagreeing with you about the connection with capitalism as such or even with your argument here at all. It was not really a point you were discussing here, for obvious reasons: it is more that this same connection with capitalism has been used in some circles, with some overlap with fannish circles, to argue that copyright in any form is intrinsically exploitative and needs to be opposed. That is, obviously, not a position the SWG has ever adopted. And I wasn't suggesting you had.

But I think others of your readers may well have seen it recently argued elsewhere, like me.

Gotcha! Thanks for…

Gotcha! Thanks for clarifying.

My personal stance is that copyright is a good thing because creators being able to make a living on their creative work is something I support, but I do think we need to be on guard against abuse of copyright, i.e., Disney lobbying to extend the term before a work goes into public domain to continue profiting on Mickey Mouse or rights holders going after amateur creators who are not profiting from their use of a work (or, again, Disney going after schools that show their films for "movie days" without a curricular connection).

I was saving this for when I…

I was saving this for when I really had the time to read it and I was, unsurprisingly, not disappointed about how thought-provoking and interesting it would be. A fascinating collection of data that will very likely change as the TV series progresses - will we get a new wave of fans that started reading the book to see if Galadriel/Sauron really were a thing? Lol I do hope so! And I wouldn't say it is necessarily a bad thing if a new fandom for the series appeared!

But I think it all comes down to your last paragraph: making choices to prioritize the story, whether that takes canon into consideration or not - we follow the cravings of the Muses lol. But I do think that, the more we engage in fandom and read other people's works, more likely we are to "deviate" from our original purpose. I set out to write one specific, very non-canonical (smutty) ship, but now I love writing about Gen stories, different takes of the same characters and even canonical ships where before I would never. Anyway, long ramble short: an excellent read, as usual! Thank you for writing and sharing it with us!

I was saving this for when I…

I was saving this for when I really had the time to read it and I was, unsurprisingly, not disappointed about how thought-provoking and interesting it would be. A fascinating collection of data that will very likely change as the TV series progresses - will we get a new wave of fans that started reading the book to see if Galadriel/Sauron really were a thing? Lol I do hope so! And I wouldn't say it is necessarily a bad thing if a new fandom for the series appeared!

But I think it all comes down to your last paragraph: making choices to prioritize the story, whether that takes canon into consideration or not - we follow the cravings of the Muses lol. But I do think that, the more we engage in fandom and read other people's works, more likely we are to "deviate" from our original purpose. I set out to write one specific, very non-canonical (smutty) ship, but now I love writing about Gen stories, different takes of the same characters and even canonical ships where before I would never. Anyway, long ramble short: an excellent read, as usual! Thank you for writing and sharing it with us!

Extremely interesting,…

Extremely interesting, written with exemplary clarity, and complemented by a stream of illuminating comments. Speaking as a 'Tolkien scholar' (I don't hang out on twitter!), my long journey over the years has brought me round, slowly but surely, to the conclusion that Tolkien fan-fiction has to be one main vehicle of Tolkien scholarship. From my own experience, I just don't see how one can think cogently about stories without having some sense of what it means to put one together (I've only put one together, and have no natural talent for it, but it was an extremely rewarding learning experience). Tolkien could certainly put together a logical argument, but his genius, in his scholarship as much as his fiction, was to think in story.

Anyway, reading all the above from the point of view of the 'scholarly canon' I keep returning in my mind to the account of a story as a spell that appears in 'On Fairy-stories.' Tolkien talks of a moment of disenchantment when some element of a story appears incredible and we pop out of the secondary world of the story and find ourselves again in the primary world, looking at the abortive secondary world from outside - the spell is broken. As I understand what Tolkien is saying here, stories inherently involve authority, for an audience must place trust in the storyteller; but the storyteller must gain that trust, and can lose it. Now an oral storyteller, as you say, suits the form of the tale to the audience of the moment, but a printed story is caught in a moment and the world is always changing. Some spells that worked in, say, 1921 or 1954 or 1977 don't work the same anymore. Without constant negotiation, much of the magic will eventually wither and the secondary world will slowly die - or more likely be changed into something completely different, because a story that no longer works has appeal only to historical scholars, not those who today wish to be enchanted. I have a sense of this survey and analysis of Tolkien fan-fiction as providing an image of that negotiation in action.