Fandom Voices: Defining Canon and Using Canon in Fanworks by Dawn Walls-Thumma

Posted on 22 April 2023; updated on 17 June 2023

This article is part of the newsletter column Cultus Dispatches.

Part One: Defining Canon

I write this under the shadow of Tolkien's canon, by which I mean that, if I look up, I have three shelves of books on the wall over my head stuffed with Tolkien books. These three shelves are the physical embodiment of what is obvious to any Tolkien fan: Tolkien's canon is complex. If you're reading this, I expect you know this.

But this complexity is precisely why, for the next few months, I've decided to dive into the question of canon: exactly what it is and how different Tolkien fans define it and use it for their various fannish purposes. For this article, which is part of my Fandom Voices series that seeks to document the memories and experiences of fans, I asked two questions and invited fans to respond to them: "As a Tolkien fan, what do you consider canon?" And, if you create fanworks, "How do you use Tolkien's canon (or maybe you don't!) in the fanworks you create?"

This is the fourth Fandom Voices article, and it has received the most overwhelming response so far. As of writing this, I've received forty-five forty-six responses, and many of them are lengthy. A couple of respondents apologized for writing an essay. (They didn't need to. As a researcher into Tolkien fandom, these forty-five forty-six luscious responses felt like how I imagine Scrooge McDuck feels while backstroking through his room full of gold coins.) And the level of thought and analysis that went into the average response showed that this is an issue that people have not only considered but made intentional decisions around.

Due to the wealth of responses I received for this installment of Fandom Voices, I've decided to break the article into two parts. This part will share responses about how fans define Tolkien's canon. Next month, I'll share responses around how fans use (and don't use) Tolkien's canon in their fanworks. However, the responses I've received so far are available below, if you can't wait till next month to dive into the second half.

It is important to note that almost all participants in this project identified themselves as fanworks creators. Given that Cultus Dispatches is a column on the Silmarillion Writers' Guild, a fanworks-oriented site, and that it is written by me, an independent scholar who writes mostly about Tolkien-based fanfiction, that is not a surprise, but it should be borne in mind when reading through the responses and my analysis. I have to wonder if fans who experience Tolkien mostly through gaming or online discussion groups or in-person societies would have a different perspective.

On that note, Fandom Voices projects are living projects, meaning that I leave them active and update them as new responses come in. I'd still love to hear from people on this question, and while I won't rewrite the article to accommodate new responses, I will add new responses to the collection below. If you want to contribute a response, you can find the responses form for Fandom Voices: Defining Canon here.

What Works Are Canon?

The One Thing We Can Agree On (and It Really Is Just One Thing)

So which of those dozens of books literally looming over me right now count as canon? As far as points of agreement, there was only one across all of the responses I analyzed for this article: The Lord of the Rings (LotR).

While many fans included The Hobbit, not all did, in recognition of the fact that The Hobbit was retconned into the legendarium after its publication. (This is something I noticed too: the awareness of the textual history of Tolkien's various writings was quite impressive as respondents discussed how they build a canon out of his many books. In 2017, Corey Olsen gave the keynote at the Tolkien at UVM conference, making the case that The Hobbit was not written as part of the legendarium. Six years later, this is no longer a keynote-worthy theory but, for many fans, has become … well, canon.)

"Well, the LotR and The Hobbit are definitely canon," begins one respondent begins with confidence before immediately offering a parenthetical caveat: "(with one exception—the Dwarves helping build Thranduil’s halls, because clearly, Professor Tolkien worked his ideas about Menegroth into that at a time where he thought The Silmarillion would never be published)."

Another respondent is careful to note the revised edition of The Hobbit, by which point Tolkien had brought it into the legendarium's fold: "LotR, [LotR] appendices, the revised edition of The Hobbit, The Silmarillion, and non-contradictory parts of the Histories of Middle-earth are what I consider canon in general, in that order of precedence."

And another anonymous participant explains this as:

The Lord of the Rings is the only text I consider 100% canon all the time. The Hobbit is mostly canon, except when there are worldbuilding inconsistencies that are due to its early composition and not originally being part of the legendarium, in which case I give precedence to the evidence in other texts.

As noted above, however, many respondents did consider The Hobbit to be canon. Another common designator was that, to count as canon, the text was published in Tolkien's lifetime. Daniel Stride, for example, states: "The Lord of the Rings, the revised Hobbit, The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, and The Road Goes Ever On. The texts published in Tolkien's own lifetime." (Note the word revised is appended to The Hobbit in his ranking too.)

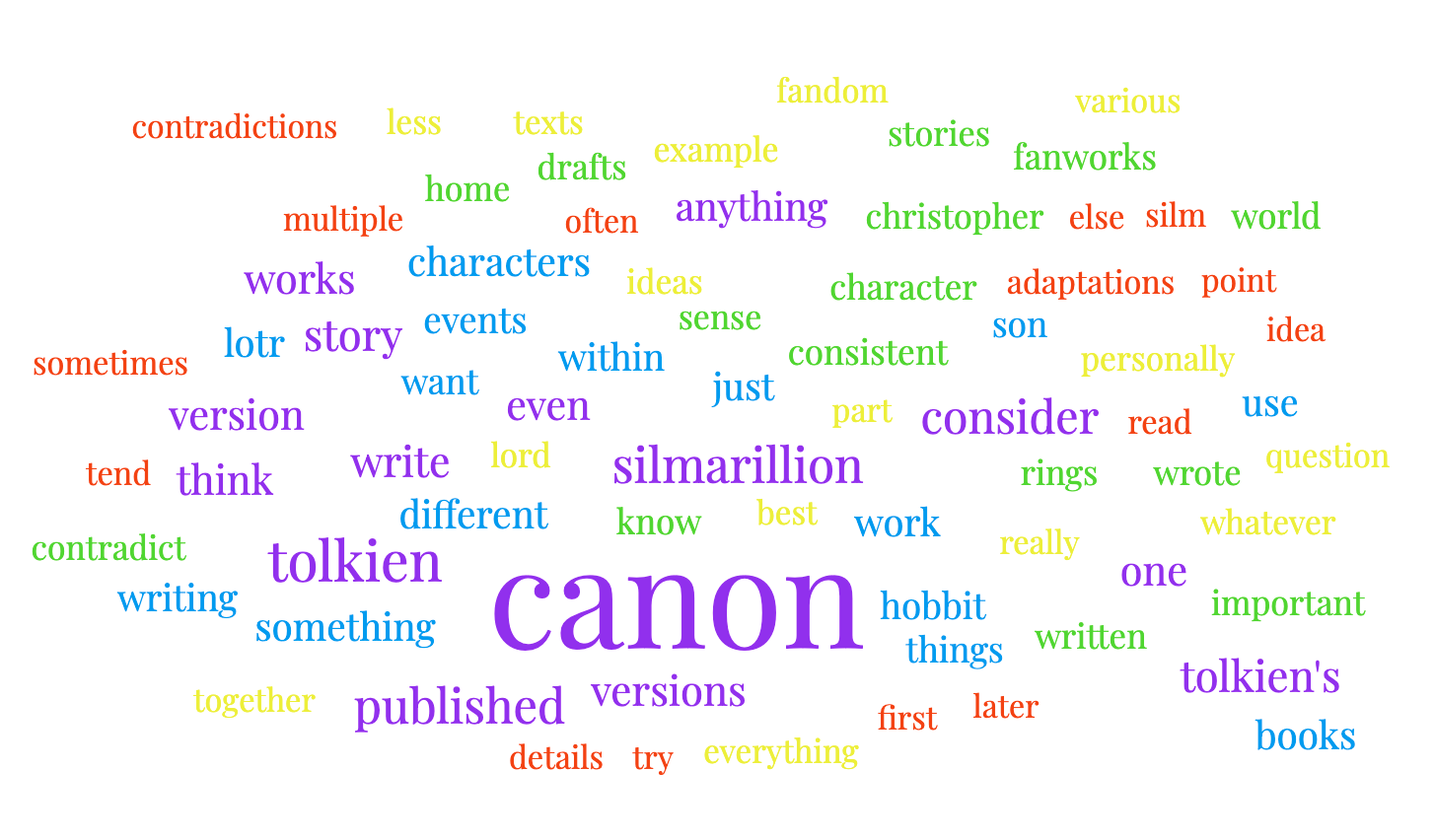

But the one canon text everyone agreed on was LotR. The word cloud below shows the seventy-five most frequent words in the responses, and if you combine Lord of the Rings and LotR, they appear thirty-nine times: the sixth most-mentioned word/phrase in the results.1 No one said that LotR wasn't canon to them, although as will be seen in the next section, many respondents did raise issues that complicates the canon from LotR.

Navigating The Silmarillion and Related Texts

Something I noticed as I read through the responses for the first time—aside from the intentionality evident in participants' thinking about canon—was the number of people who used metaphors and analogies to describe their approach to canon. This alone spoke to the need of participants to concretize what otherwise felt abstract and complex. (Even the subheading for this section is metaphorical.) As I share the many ways fans steer through the mazy waters of Tolkien's posthumous works, I will title each section with one of these analogies.

Once we move beyond the works published in Tolkien's lifetime, defining canon becomes much more complex because the history of the texts themselves becomes much more complex. The Silmarillion and subsequent works were posthumously published, made available to us through the editorial efforts of Christopher Tolkien and others. Any time an editor becomes involved, the matter of selection becomes paramount, but in the case of The Silmarillion and other coherent narratives, Christopher Tolkien made changes to achieve that coherence and, in some instances, wrote the text himself, with the assistance of Guy Kay, when his father didn't leave adequate usable material to construct a coherent story. That an entire book (Arda Reconstructed by Douglas Charles Kane) exists to document what in The Silmarillion came from where is a physical embodiment of The Silmarillion's complexity.

The History of Middle-earth (HoMe), Unfinished Tales (UT), and The Nature of Middle-earth (NoMe) in some ways show Christopher's work, but they also introduce their own complexities by giving fans much closer access to texts that were hard to date, hard to read, sometimes rejected, never intended to be read, and that can be hard to contextualize—and yet offer tantalizing details and a wealth of material that begs to be fitted into the canon.

"The Heart of Canon": The Silmarillion as a Third Canon Text

I take The Silmarillion as canon (perhaps the heart of canon) …

~ Anonymous

Many respondents shared that they consider The Silmarillion a canon text on par with LotR and The Hobbit. However, as polutropos summed up, canon is "[a]nything written by Tolkien himself, with all their contradictions. Editorial changes and additions by Christopher Tolkien for the most part, but this is a grey area."

The gray areas are what makes the predominance of the Silmarillion-is-canon camp so interesting. As noted above, The Silmarillion isn't just posthumously published and isn't just compiled by Christopher (not J.R.R.) Tolkien, but sections of it were entirely written by Christopher, with the assistance of fantasy author Guy Kay. As polutropos's response suggests, though, fans who consider The Silmarillion as canon have thought about these matters and made the intentional decision to take the published Silmarillion as canon. As one participant noted, The Silmarillion is less definitively and perfectly canonical than simply the "most canon" of the available options:

I would personally call The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion "most canon", even though they do contain contradictions. I would call the J.R.R.-written parts of the published Silmarillion the "foremost authority" on the First Age where it and the other two books conflict, but LotR the "foremost authority" on the Third Age.

Other participants saw The Silmarillion as canon as providing a useful framework through which the First Age histories are best understood. "Notwithstanding the issues associated with the 1977 Silmarillion," wrote Daniel Stride, "I find it useful as a coherent framework—Tolkien's later material (e.g., the round world) is often too undeveloped, and often not to my aesthetic tastes." Another participant found value in the Silmarillion-as-a-framework not just for making sense of the early histories but in discussing them with other fans:

I also accept The Silmarillion as canon, but more because it provides a framework with which to discuss the First Age with other fans than because I think this view is consistent with my other views—which do not accept anything published after Tolkien's death as canon.

The published Silmarillion also provides a single coherent story, which has its appeal to some fans. As one respondent writes:

I understand there is debate about whether Tolkien's unaltered notes about lore should be considered pure canon instead of the more heavily edited, polished collections. In my opinion, they can be considered separate canons without cancelling each other. Christopher edited original texts to make The Silmarillion a smoother, more coherent story, but I don't think he uncanonized the stories by doing so. To me, he just gave an extra option to fans who don't want to read a collection of inconsistent, unedited notes!

Furthermore, some fans reject the HoMe and similar texts as canon because they don't have access to these texts, which are not published worldwide, unavailable in most languages, and expensive to procure. Cuarthol raises an important point about equity in the fandom where access to books is concerned: "Not everyone has access to the various histories and books that have been released … and all the information in them is not universally known, and it is best to accept that any one of them can be taken as correct."

Another common thread throughout the responses was trust in Christopher Tolkien's judgment. "[A]fter reading the Letters …" writes Anérea, "I've come to realise that Christopher played a larger part in the formation of his father's ideas than we may realise. … So I'm content to allow his input and interpretations to be considered canon too. (Including his admitted mistakes, although those carry less weight IMO.)" Polutropos likewise identifies Christopher Tolkien's "great care" in compiling The Silmarillion as a reason why it is the predominant canon text of the early histories. When choosing between contradicting versions, she writes,

I would consider the "ripple effect" or picking one version over the other—something Christopher Tolkien had to do for the published Silmarillion, and he did it with great care—one of the primary reasons why, when in doubt, I will fall back on the published Silmarillion as The Canon.

The Silmarillion has also been published the longest of the posthumous works. Although publication of collections of drafts and notes (beginning with the Unfinished Tales in 1980 and the first History of Middle-earth volume in 1983) started not long after the publication of The Silmarillion in 1977, these books were harder to obtain in the pre-internet era, and another coherent narrative that could be read like a novel wouldn't hit the shelves until 2007 with the Children of Húrin—thirty years later. As one respondent explained,

[A]s an older reader, I became really familiar with the originally published versions of LotR, The Hobbit, and The Silmarillion, before any of the rest appeared. So these have become ingrained in a different way than versions I encountered later, and I still default to them in a way others who have encountered the material in a different order might not.

And finally, even among the fans who name The Silmarillion as capital-C Canon, they do not see that choice in straightforward terms. To give the full statement from the respondent who gave this subsection its title: "... I take The Silmarillion as canon (perhaps the heart of canon), again with a bit of caution concerning the ruin of Doriath, as Professor Tolkien never worked out a version of it he was satisfied with."

Ask not the Elves if The Silmarillion is canon, for they will answer both no and yes …

"Schrödinger's Canon": Contradictions and Consistencies

Even if contradictory, it can be Schrödinger's canon.

~ Anonymous

For other respondents, contradictions and consistency among the myriad versions of Tolkien's work were chief concerns in defining canon. Evidencing this, the word consistent appears eighteen times in the responses and the word contradict fifteen times. This comes as no surprise. Many of Tolkien's posthumous works—which, as he noodled with ideas, he never could have anticipated would have an audience in the tens of thousands—directly contradict each other and his other works. We often see him "thinking on the page," a process likely familiar to any fiction writer but disorienting when confronting those multiple versions out of their creative context. Furthermore, Christopher Tolkien's own work constructing the published Silmarillion prioritized consistency above other concerns. Even though Christopher later questioned his own choice in this matter,2 the effect was still the same: the first posthumous text, The Silmarillion, was edited with consistency as its overarching concern, and discussion of drafts in subsequent publications therefore always circled back to consistency. It is no wonder, then, that fans also perceive canon through this lens, even if they ultimately reject Christopher's approach.

For many fans, contradicting details from the posthumous works are excluded from the canon. Of course, the baseline against which other texts are compared and found to be contradictory is itself an open question, given this approach. Are the texts published in Tolkien's lifetime the baseline texts? One participant explained this approach: "I do consider everything J.R.R. Tolkien wrote to be canon, for varying definitions of canon; some of what Christopher Tolkien wrote for The Silmarillion I would also consider to be canon, if nothing written by J.R.R. Tolkien contradicts it."

Gideon Cooper more narrowly defines canon as any details from the posthumous texts that validate those texts published in Tolkien's lifetime:

And then of course all of this is even more complex and less rigid when applied to the earlier era writings. And, to be honest, I only consider anything within HoMe, NoMe, The Silmarillion, The Unfinished Tales, or the essays "best to assume" canon if their absence would make an aspect of LotR or The Hobbit not make sense, or if it is actively mentioned within those books or appendices. Everything else is so contradictory and has so many possible avenues of difference that it really cannot be argued as "strict" canon at all.

The baseline against which contradiction is determined can also be Tolkien's final word or what appears to be his most reliable word, repeated over multiple drafts and necessary for other aspects of the legendarium to exist. One participant described such an approach:

Anything written by J.R.R. Tolkien himself after 1930 and either verified in more than one draft or present as the only version or explanation. This explicitly and purposefully excludes fanon, fan preferred headcanons, "this happened in one draft and no others" unless it’s the only available rendition, "this happened in an early draft but later versions contradict it" (specifically Maglor’s survival), and anything only present in the published Silmarillion (because Christopher has a tendency to invent things out of whole cloth, like with Maeglin, or exclude details that drastically change the nature of the story, like with Túrin).

Contradiction doesn't have to reside only in specifics. The canonical baseline can also exist in a more nebulous understanding of how Arda operates as a consistent Secondary World. One respondent explained this approach: "Contradictions are an important factor for me apparently, not just in the exact letter but also does it still fit with the overall state of the world and themes of the pieces I consider canon?"

But Christopher Tolkien's (and many fans') preference to strike inconsistencies from the canon is not the only approach. One of my favorite of the many analogies to emerge from respondents' explanations of how they define canon comes from an anonymous respondent and gives the title to this section: "Any version of events and characters in stories (not letters and footnotes) that are published, I'd consider canon. Even if contradictory. It can be Schrödinger's canon."

Until you open the book, Gil-galad's father is both Fingon and Orodreth.

While consistency and contradiction is a prominent theme in the responses, many fans are content to accept Schrödinger's canon: that multiple versions can be true at once, all of them equally canonical. As we will see in the The Most Glorious Kaleidoscape section below, some apply historical and mythological frameworks—themselves rooted in the canon—that allow for multiple versions, but not all fans need this framework to be comfortable with inconsistency.

Cuarthol's response embodies this comfort with Schrödinger's canon and the idea multiple conflicting facts can nonetheless all be considered true:

And that is why my … more preferred (personally) approach is, Canon for Tolkien is literally anything we have in written form that he said about his world, even the contradictions. Gil-galad is as much Fingon's son because it was what was put in the published Silmarillion as he is Orodreth's son because that's what Tolkien "wanted." Celebrimbor is the son of a Sinda and a smith out of Gondolin and the son of Curufin because these all exist.

The rigors a text undergoes in order to achieve publication, in some instances, was enough to codify a detail as canon, even if it is contradictory. Firstamazon writes that canon is

[w]hatever is officially published. I know that it's a very wide range of different information, but I consider that publishing something is also undergoing critical analysis, and whether or not someone agrees with an editorial choice, it was still a conscious choice and therefore a valid one, enough to be considered canon.

Similarly, Idrils Scribe observes that the expansion of Tolkien's canon means that the concept must make room for new ideas and details, including those that might be contradictory to what is accepted as canon: "To me, canon is all of J.R.R. Tolkien's work that is currently available to us. Canon continues to expand as more gets published. Contradicting or abandoned versions of the same event/character are both canon."

Egg's response embraced the difficulties posed by Tolkien's work as belonging just as much to the canon as his tidier texts: "I consider the 'canon' to be anything Tolkien wrote, inconsistencies, obscured plot points and plot holes, and all. Including his letters, songs, and poems."

Fuzzy Canon: Tolkien's Final Word

I've since become aware of the unique fuzziness of Tolkien's canon ….

~ Anérea

When I first started participating in the Tolkien fanfiction fandom, canon was discussed just as enthusiastically then as it is now, and I recall that "Tolkien's final word" was frequently mentioned as the determining criterion for the canonicity of the posthumous texts. I was a bit surprised that it was not mentioned more frequently in this set of results, but I wonder if this is, as Anérea's quote above suggests, because the publication of many more volumes, the increased availability of the History of Middle-earth, and fan and academic scholarship have made fans more generally aware of Tolkien's writing (and Christopher's editorial) processes. Anérea uses a gentle, almost huggable, word to describe the result of these processes: fuzziness. Because this is much nicer than the words I think in my head while trying to untangle the skeins of Tolkien's writing to find a "final word" in there, we'll go with fuzzy.

Cuarthol was one of the only respondents to directly state Tolkien's final word as a factor in determining canonicity, although she immediately qualifies (and complicates) this criterion:

Tolkien's canon is whatever his final word was on a topic, as best as we can determine. So Gil-galad is Orodreth's son, and Orodreth is Angrod's son, because in the end that is how Tolkien wanted his story. And yet this is the most unrealistic view of canon due to there being no ability to know absolutely what his final thoughts were on a subject because we are, of course, limited not only to what he wrote but limited to what has been released to the public of what he wrote.

Other participants didn't speak directly to the challenge of determining Tolkien's final word but brought up the kinds of complications that tend to plague the endeavor of trying to order the texts and tease out a definitive answer as to a final, definitive word. Returning to Anérea, she raises the question of authoritativeness of the later publications compared to the much earlier Silmarillion, specifically speaking to how this new information gives authority to some versions of the canon over others:

But with each successive book published after The Silmarillion the boundaries of the canon become less and less distinct. (I was quite surprised to learn that the HoMe is not widely accepted as canon! But what of the individual books most recently published: Beren and Lúthien, The Fall of Gondolin, The Children of Húrin, The Fall of Númenor? Are they not canon because they're not the published Silmarillion, or because they contain multiple versions and internal contradictions? Oops! I'm asking questions where I'm supposed to be answering! Okay, so thinking about this now, I think I'm seeing these latter volumes as having more authority, or rather, giving authority to the tales and versions of tales they contain.)

Lyra also expresses the challenges of ferreting out Tolkien's "final" or most reliable word, noting that both the early and late extremes in his writing tend to pose problems for canonicity, though for different reasons:

It's more difficult for The Silmarillion, where Tolkien changed his mind back and forth! Generally, I tend to assume that the earliest writings (like The Book of Lost Tales) are less reliable, and elements from them are only "canon" if they don't contradict any of the later writings. The later writings aren't always reliable either, since Tolkien was prone to experiment but then return to an earlier version (which Christopher Tolkien has thankfully often documented, but sometimes the situation is less clear). Nonetheless, I tend to consider the latest finished (!) version canon, and where there is no finished version of a story, the elements that have survived (mostly) unchanged are harder canon than those that were only used once or only introduced at the last minute, so to say.

"The Most Glorious Kaleidoscope": Canon as History, Translation, and Myth

That allows for bad takes, incorrect versions, mixed histories, and straight-up unreliable narrators or "bad translations" to allow for the most glorious kaleidoscope of options.

~ Cuarthol

As I noted in Schrödinger's Canon above, many fans reconcile the myriad contradictory versions of the canon using a detail from the canon itself: that Tolkien wrote his tales as though they were historical or mythological texts. As several respondents noted, this grants a lot of leeway in allowing multiple variations to exist as equally canonical. After all, the histories (and certainly mythologies) are just as muddled. Élodie expresses this idea in their comparison of Tolkien's texts to real-world folklore and myth, where the idea of a contradictions and canonicity are less important than an understanding of historical context:

I like to think of Tolkien's work as a mythology, and the global diegesis of his works lean into this interpretation: every text is supposed to be written by an in-universe writer, with their own interpretations, sources, bias and so on. And in the same way, mythological texts or tales vary depending on the source, the time they were written down or gathered. For example, is there a more canon version of the story of Beauty and the Beast? Regarding mythology, I majored in Egyptology in university, and ancient Egyptians did have numerous variations on the myth of the creation of the world, that coexisted and changed depending on the area (and the time period).

As several respondents observed, the idea of Tolkien's texts as historical or mythological is a sort of ur-canon that supersedes all other considerations of canonicity. "Even with the two published books," writes Marta B, "I like to remember that Tolkien himself switched his stories on how Bilbo found the Ring …." He did this by leaning on a historical device: Bilbo as an unreliable narrator who lied to preserve his own reputation.

Nathaniel Maranwe settles the question of canon and contradictions and which version is "true" with the reminder that

The only actual known "true" fact is that Tolkien found and translated some old documents! Conflicting drafts could just be because translation is hard. None of our narrators are 100% reliable. Including Tolkien himself (though I personally believe the Professor would have done his best).

Nathaniel Maranwe was not the only respondent to consider Tolkien himself in the chain of historical transmission (as Tolkien himself did) and to offer Tolkien's fallibility as another potential reason for the welter of texts published under his name.

Gideon Cooper likewise sees discrepancies in the texts not as a flaw or a problem to solve but as an important element of the canon. Speaking of LotR, they write,

… we are reading an in-universe compiled account of a historical war as authored, edited, and recompiled through many centuries and many hands. Given the nature of historical documents, all manner of discrepancies suddenly become a PART of the canon and almost everything about the events in the books are given a far shakier relationship to canon than most stories allow.

For fans, regarding the texts as in-universe histories and myths, subject to all the complexities of those genres in the Primary World, solves problems of canon. Particularly, the matter of how to handle contradictory texts can be resolved using this approach. Polutropos finds that different versions invite her, as a fanfiction writer, to consider how all versions can be reconciled within the historical record:

In blending multiple versions, I like to consider the plausibility that they would exist in the same branch of a cultural tradition. For example, I do not find it plausible to write Daeron as Thingol and Melian's son, as he is the Lost Tales, if I am otherwise remaining consistent with the published Silmarillion where, for example, he is sent as an emissary to Mereth Aderthad. Instead, I write Daeron as their minstrel but with a relationship to them that some storyteller somewhere along the line might have interpreted as filial. I could go the other way, and accept him as their son, but for me that would involve making much more drastic changes to the surrounding story that I don't want to make. …

Fortunately, puzzling out ways to make things fit is a large part of the joy of writing fanfic for me. Combining versions is great, but to me it's not simply a free-for-all "mix and match", but a complex puzzle. It's important to me that whatever amalgam I come up with fits together relatively seamlessly. I want it to have internal consistency and logic.

Another respondent finds that the contradictory versions of the texts, when viewed as myth where multiple variations are not just permitted but expected, can foreground important themes in the text ahead of specific details:

I consider the entire Mythology to be canon. When I think about manuscript tradition, I think of how, for example, there are several versions of the same poem from different codexes that must all come from a singular source, but their varying transcriptions and scribal choices create entirely new texts with the same themes running throughout. In the same vein, as Tolkien was writing a created history, I consider the various drafts to be manuscripts of a sort, that get modified and adjusted. Melko being a primitive beast that runs up a huge pine tree and hurls down stars can be the same figure as Morgoth, whose power dwells in the earth of Arda. The contradictions of facts (if we want to call them facts) are actually irrelevant to the deeper themes that run throughout the entirety of his writing.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, for participants who were fanworks creators, this approach can inspire the creation of fanworks. Cuarthol, whose quote provides the subheading for this section, sees the added possibilities of a historical approach as expanding options for fanworks creators to fit the canon together in new and vibrant ways—a kaleidoscope:

And while there may be an argument that the various versions are equally valid but perhaps should not be mixed together (that is, Amrod dies in the fire when only Curufin helps burn the ships, and Maedhros does not alone stand aside), in the end these are all put forth as histories recorded within the universe in which it takes place. That allows for bad takes, incorrect versions, mixed histories, and straight up unreliable narrators or "bad translations" to allow for the most glorious kaleidoscope of options.

Pandemonium_213 sees the historicity of Tolkien's works as expanding the canvas upon which fanworks creators work by allowing them to venture beyond the limited stories we are given:

All of his works represent so-called canon. I like to view them as a collection of myths that allows creation of fanworks in settings that are recognizable as Tolkien's Secondary World. … I like fanworks that recognizably take place in Tolkien's milieu, but strict adherence to so-called canon is unnecessary, and in fact, restrictive, which is inconsistent with a mythology.

Likewise, remembering that the in-universe authors, historians, loremasters, compilers, and translators are themselves characters can provide another layer for exploration in fanworks. As Gideon Cooper notes, "One could, for fun or other reasons, speculate on the motives in-universe editors and compilers (like Findegil) might have had for twisting events to the 'victors' benefit. And authors have!" They also observe that the status of the texts as translations, especially given the centrality of language to Tolkien's legendarium, offers fertile ground for fanworks creators to question what was lost or changed in translation:

With language being such a vital part of the books' conception as a whole, and the book we read already being canonically and irrevocably changed through translation from Westron to English, and character names even being altered, this all was already up for debate. … There are some things to be lost in treating these aspects of the text as ambiguous … but there are also things to be gained as well and new interesting meanings to be gleaned from different ideas and perspectives. What if Galadriel's golden hair was actually literally metallic gold? What if when Sam called Frodo "Master" he was actually using a different term that could be a more familiar one of endearment than the translation allows?

Marta B. sees regarding the books as historical texts as granting a lot of freedom to fanworks creators:

… since [the books are] framed as historical documents there's all the problems of bias and POV [point of view] inherent in any history at play. All of which means I think we fanfic writers have more freedom to bend and even contradict well-established, published-in-JRRT's-lifetime canon. I do think the more commonly known a canon fact is, the more we're going to have to work to make a contradicting story believable; but that's a matter of degrees, effort, and skill, not a binary thou-shalt-not.

Marta's emphasis here on skill (not convenience) is an idea that surfaces several times as authors discuss interpreting canon as history and myth. Along a similar line, polutropos notes that this approach is not carte blanche for an author to simply do what they want and call it canon:

It is also important to me not to use the narrative conceit of Tolkien's writings as an excuse to completely disregard what's written. That is just rude to Pengolodh and Rúmil and the rest as historians! I assume that they were capable chroniclers who did their best to give an accurate version of events.

Taken with polutropos's earlier remark about the "complex puzzle" that ensues from trying to reconcile multiple versions of the canon, making a workable, appealing fanwork within the historical framework given becomes part of the art and unique challenge of making stories, art, and other fanworks within Tolkien's canon.

"Interesting Blank Spots": Non-Contradictory and Not-Necessarily-Rejected Canon

"... gaps around canon where there's interesting blank spots and underwritten characters."

~ Aipilosse

Of course, not all details from The History of Middle-earth and similar texts are contradictory. Nor did all of these non-contradictory details make it into the published Silmarillion. Nor were all of these non-contradictory, non-Silmarillion details rejected by Tolkien.

That creates a collection of facts that, while they might not fall within a particular fan's definition of canon, can be tacked onto their understanding of canon without altering it: providing a canonical answer to the "interesting blank spots" that could and do exist in the texts. Several fans shared a willingness to include such details as canon.

In the Schrödinger's Canon section above, I quoted from a participant who observed that Christopher Tolkien, in the published Silmarillion, sometimes "exclude[s] details that drastically change the nature of the story, like with Túrin." She was not the only one to flag Túrin's story in the published Silmarillion as lacking. Another respondent explains it as such: "The Children of Húrin has greater canon status than the version of Túrin's story in The Silmarillion, because it's much more fleshed out."

The HoMe likewise includes details that do not contradict other parts of the canon and were not definitively rejected by Tolkien. StarSpray provides several examples that expand the presence and roles of women in The Silmarillion:

I primarily pull from the major works—LotR, The Hobbit, The Silm (I like Gil-galad son of Fingon)—but if there are details in HoMe or the Letters or something that I like, such as the existence of Lalwen and Findis, or the extra details we get of Nerdanel, I’ll take those and run with them, while feeling free to ignore the stuff I don’t like or that contradicts other canon, like some of the retconned stuff from Unfinished Tales or [Laws and Customs among the Eldar].

Independence1776 defines canon rather strictly as the three major works but likewise leaves room for these appended details:

The main three books are canon: The Hobbit, Lord of the Rings, and the published Silmarillion. Everything else is not. I treat HoMe (and other works such as NoMe) as strictly supplementary information, though there are a handful of things like the Round World version, more information about Nerdanel, and the existences of Findis and Lalwen that I treat as canon.

Again, the willingness even by fans with a rather strict approach to canon to include such details speaks to the importance of consistency and contradiction to many fans. If the detail does not create a contradiction, for many, it is fair game to fall within the scope of canon.

"Set Pieces": Canon as a Social Construct

Clearly "we" as a fandom, and even those outside of it completely, have come to understand Tolkien's works enough to agree on a mostly generous consensus about characters, plot points, and major events, and enjoying them as the definitive set pieces of the story (or what we all come to mean when we say "I like/don't like LotR").

~ Egg

In the The Heart of Canon section above, some participants frame The Silmarillion's value as a primary canon text not in terms of its factual superiority and more in terms of its social utility: It provides a framework for understanding the histories of the First Age and earlier and discussing them with other fans. A few respondents took this idea even further, defining canon primarily as a social construct: a shared set of understandings that allow fans to discuss, create based on, and otherwise enjoy Tolkien's works together.

Egg's quote that gives the title to this subsection gets at this with her analogy of "set pieces." Given that modern fandom mostly occurs in virtual spaces, these set pieces allow us to enter into interactions with shared expectations and navigate through social situations, much as the "set pieces" of in-person social spaces do: a living room, a pub, a concert hall.

Gideon Cooper's response used the concept of the books as historical texts to fully define their canon, conducting a deep analysis of what we can definitively accept as factual. This opens up the canon considerably, dismissing even some of the facts of LotR as canonical. They conclude that one of the primary values of canon is to provide a shared understanding in the fandom:

Which is all to say that, the first layer of rigid canon is canon because it must be true for the world to exist. The second layer of canon, which I define as the physical events that are described in LotR (and in a sub-layer The Hobbit, although Bilbo already creates ambiguity there) and that are not subject to one single character's personal recollection of it (Boromir's last words that only Aragorn heard for example) are canon because they "best be so" for the overall coherence of the fandom at large. They are also the least likely to be false, being major historical events remembered by many other characters. …

But in terms of the broad Tolkien fandom, and for purposes of collaborative character and theme analysis and just general enjoyment overall, it is best that we all hear "Gollum fell with the ring into Mt. Doom and Sauron was destroyed and the war was over" and nod our heads.

Marta B. took a similar approach but applied it specifically to fanworks, making the case that canon can be audience-dependent, with fanworks creators having more freedom to manipulate and change some canon over others, depending on whom they see as the primary audience for their work:

That means (in the context of fiction) canon is essentially whatever the author wants to make use of and can reasonably expect their audience to be familiar with. Which is obviously something that's relative to each audience and author. …

I think of canon as whatever helps me frame the story most interestingly and what I can reasonably expect my reader to know. That depends a lot on what I'm writing; a story about Ar-Zimraphel could easily pull from the UT essay on Númenórean religion, because there's so little Númenor material I'd expect any Númenor fan to have read more than just the Akallabêth. But for a story about Denethor, the essay on the palantíri is much more esoteric (though probably relevant!), so I wouldn't assume my reader knew it, nor would I think violating it would pull them out of the story. So I'd feel less bound by it, and would want to lay more of the groundwork but also feel freer to write a different version.

Canon is important here less because of a need to establish a set of true facts than because of its social function. It lays out the expectations of what a Tolkien fan should know, what we should expect others (in different fandom settings) to know, and what we assume as a baseline for discussion in social situations with each other. Above, I quoted a respondent who saw the published Silmarillion most useful as canon because it served as "a framework with which to discuss the First Age with other fans"; in other words, if you find yourself in fandom space with Silmarillion fans, you can assume they have read The Silmarillion. Discussion of canon beyond that builds from there.

"Under the Same Umbrella": Where Adaptations Fit In

... there are multiple smaller canons that all sit under the same umbrella.

~ Shadow

A final consideration in defining canon are adaptations and where those fit in. In last month's column, Who Gets to Say? Canon and Authority, I shared data from the Tolkien Fanfiction Survey showing that fanfiction authors "consider[ed] other fans' views on the canon" 61% of the time and Peter Jackson's views 28% of the time. When phrasing the question for this installment of Fandom Voices, I did make the question a bit leading, including "decades' worth of adaptations in myriad forms" as a reason why Tolkien's canon is complex, in part because I hoped respondents who did (or did not) consider adaptations as canon would discuss this.

Shadow's response gives this section its name and analogizes what was by far the most common way respondents viewed the adaptations. They wrote:

For me, there is no one complete canon of Tolkien's work. Instead, there are multiple smaller canons that all sit under the same umbrella.

For example, I consider The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit books canon just as much as Jackson's movie adaptations, but they're not the same canon. They're two separate sets of Tolkien canon.

Thirteen respondents mentioned professional adaptations (films, TV, games, radio plays, etc.) and, of those thirteen, ten expressed some version of Shadow's umbrella idea: that adaptations and book canon are both fine, but they are separate canons. Interestingly, some participants dismissed adaptations as canon but acknowledge that they use aspects of adaptations in their fanworks. For example, one participate wrote:

Anything that Tolkien himself wrote about Middle-earth, and nothing else. Everything else is just an adaptation.

I use Tolkien's work as a basis for most of [my fanworks], and anything from the Peter Jackson movies, LOTRO, and officially produced RPG games material. I also draw on Norse mythology too, and any other literature that Tolkien studied.

Another participant likewise defined canon as book-based but admitted details from adaptations into fanworks, specifically visual details from Jackson's films. Scholars looking at the Jackson films have identified the visuals as more readily adopted by book fans,3 and this participant's response seems to support that. She writes:

I don't consider any animated or film adaptations "Tolkien canon," because they are interpretations by other writers and directors.

The only places I vary from Tolkien's canon is when I am describing characters and places; I am a visual person, so I use Jackson's film adaptations to help me describe what things look like.

What these responses seem to show is an approach where the books provide the canon but adaptations become one of many sources of additional inspiration when creating fanworks. Anérea calls this a "sub-canon": "Outside of the editorial efforts of Christopher, Hostetter, and others, I consider the rest (including movies) to be adaptations, and thus containing their own discrete canon, part overlap and part sub-canon." The response above citing Primary World mythological and literary sources as inspiration for fanworks suggests other sub-canons.

Further emphasizing the idea of separate canons, some participants specifically noted that they were clear when working with canon from adaptations rather than the books. For example, Aipilosse writes, "I consider the [Peter Jackson] films and now Rings of Power as something separate and would preface any discussion referencing them as including movie canon or TV canon." Referring to fanworks, Shadow writes, "In LotR and Hobbit, that usually means that I will tag a fic with the movie fandoms if a story is based on one of those scenes—e.g. I wrote an Éowyn fic recently that was based on Aragorn's departure to the Paths of the Dead, so it went under Movies rather than Books."

Others preferred to keep adaptations separate from the idea of canon. Among these responses, a disconnect from Tolkien—an inability to actualize what he would have wanted from a professional adaptation of his work—forms the crux of these responses. "[Peter Jackson's] films are (rightfully!) considered to be cinematic masterpieces," writes Egg,

if not the definitive version and vision of LotR/Tolkien to the average person. (How one personally feels about this obviously depends on the person.) It is still an adaptation however, and a flawed one considering its source material. It cannot adapt and depict Tolkien's vision in a way that flawlessly matches Tolkien's intentions. It's impossible. …

Anything claiming to be a formal adaptation or addition into the legacy meant for widespread appeal and consumption should do its best to recreate what was written (not accounting for creative or stylistic choices).

Idrils Scribe voices a similar view: "I don't consider adaptations (movies, TV series ...) to be canon, because JRRT wasn't involved in their creation. There's no telling whether they match his vision of his world."

Interestingly, as seen above, Christopher Tolkien—while questioned and sometimes doubted by fans—is more likely to be assumed to know how his father would have preferred to have his work presented. Proximity to Tolkien, in this case, seems to confer canonicity, even if (as Egg points out above) the Jackson films have become the "definitive version and vision of LotR/Tolkien to the average person." In past columns, I have made the case that, despite the films' undeniable influence on fans, the fandom (especially the fanworks fandom) remains primarily book-based. It can be hard to riddle out how both can be true: how seeing the films can be such a powerful, sometimes formative experience for fans, yet the films come to play little to no role in their eventual fandom experiences. Responses here would suggest that the answer to the riddle might lie in the definition of canon: in seeing adaptations as subsidiary to the books.

Of course, not all adaptations are professional—in fact the vast (vast) majority of them are not. They are fanworks, constructed as amateur, nonprofit endeavors and meant to be enjoyed not by a general audience but by other fans. A few participants commented specifically on fanworks, fanon, and fan theories as canon. Given that the Tolkien Fanfiction Survey showed that authors considered the authority of other fans second most often, only after Tolkien himself, I wondered if any participants would extend the work of fans to the level of canon.

None did. Two anonymous participants were direct in this. "There are also no fan theories I would personally consider to be canon," one wrote, while the other's understanding of canon "purposefully excludes fanon and fan-preferred headcanons."

Yet other responses indicate that fan theories are similar to professional adaptations for many fans and especially fanworks creators, acting as a sort of sub-canon (to use Anérea's term) from which fans can draw after satisfying the requirements of the canon. Élodie described "fan canons" as an offshoot from the canon itself, especially with regards to the influence of fan art on how characters are seen: "There are also fan canons that develop and coexist altogether, especially regarding the looks of the characters, and it's also very interesting to see an iconography developing. I don't consider this as canon, but it's another way [Tolkien's] works keep on living." This parallels the tendency, noted above, of fans to draw more heavily from the visual elements of adaptations.

Egg likewise describes the canon as an important but static entity and fanworks, while not canon, as what keeps the canon relevant and vibrant—alive:

I consider Tolkien's words and intentions to be canon, but that doesn't mean I shun its transformation and reinterpretation by fans and fanworks. Even if I did, the originals will always be there. …

Otherwise, canon is great, but fanworks taking that canon and making it their own is also incredible. I try to look at it as what we all as fans have taken away from the canon, and therefore have internalized within ourselves.

Conclusion

The joke used to claim that if you asked two Tolkien fans a question, you'd get three different answers. Certainly, the variety of responses to a seemingly simple question—"What is canon?"—suggests that, when discussing canon, this is true. While themes and commonalities run through the responses, there is no predominant way that fans define canon.

What does emerge from the responses is the care and thought that many fans put into the question of canon. Even acknowledging a selection bias in this regard—the people most likely to respond are those who do care about this concept of "canon"—as I worked with the responses, they continued to amaze me in their depth and thoughtfulness. There were many examples, hypotheticals, and personal canon frameworks that I could not include in the article, so while I know the article is long, I hope that readers will find the time to read through the full responses below.

Also emerging is the idea of canon not as a rigid set of rules but a living understanding of the texts that shape their fanworks, discussions, and social interactions with other fans. Canon, in many cases, didn't seem to exist to limit but was part of the art of fandom.

Notes

- The five words mentioned more often than Lord of the Rings/LotR were: canon, Tolkien, Silmarillion, published, and consider.

- In his commentary on The Valaquenta in Morgoth's Ring, Christopher Tolkien wrote, "A leading consideration in the preparation of the [published Silmarillion] text was the achievement of coherence and consistency …. But I now think that I attached too much importance to the aim of consistency, which may be present when not evident, and was too ready to deal with 'difficulties' simply by eliminating them." The History of Middle-earth, Volume X: Morgoth's Ring, The Later Quenta Silmarillion: The First Phase, The Valaquenta, Christopher Tolkien's end commentary.

- See, for example, Amy Sturgis, "'Make Mine Movieverse': How the Tolkien Fan Fiction Community Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Peter Jackson” in Tolkien on Film: Essays on Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings, ed. Janet Brennan Croft (Altadena, CA: Mythopoeic Press, 2004), 283-305, and Miguel Ángel Pérez-Gómez, "Walking Between Two Lands, or How Double Canon Works in The Lord of the Rings Fan Films" in Fan Phenomena: The Lord of the Rings, ed. Lorna Piatti-Farnell (Bristol: Intellect Books, 2015), 34-42.

Part Two: Using Canon in Fanworks

Last month, I considered responses to the latest Fandom Voices survey asking Tolkien fans how they define the term "canon." Predictably, the results were complicated. In the same survey, I also asked respondents who created fanworks how they used canon in those fanworks. The "defining canon" results were so complicated that I decided to withhold the "using canon" results for a second article.

These results were also complicated. I have focused mostly on how closely respondents claim they "stick to the canon." Does following closely to the canon matter, or are fanworks creators happy to veer off and do their own thing? It is clear that Tolkien fans spend a lot of time thinking about what they consider canon and not-canon, so how does this thinking translate into transformative and derivative works set in the legendarium?

The Sandbox: The Populous Expanse Between Compliance and Liberality

… I'm here for the sandbox I was given. Whether I use the sand to build castles or start kicking it around with a vengeance is my prerogative, but I don't do as if the sand weren't there at all.

~ SkyEventide

Most participants did not self-identify as either compliant to or disregardful of canon. (Going forward, I'm going to use the term "canon-compliant" to refer to respondents who identify adherence to Tolkien's canon—however they define that—in fanworks as a priority or essential for them, and "canon-liberal" as those fans who are not bothered to disregard that canon for any number of reasons.) Most respondents fell in the middle between these two groups. "On a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 = not important at all and 10 = extremely important," wrote pandemonium_213 about canon in fanworks, "I would choose 5. I like fanworks that recognizably take place in Tolkien's milieu, but strict adherence to so-called canon is unnecessary, and in fact, restrictive, which is inconsistent with a mythology."

Fanworks that are "recognizably" Tolkien are a hallmark of this group, who often expressed a preference for fanworks tethered to canonical elements while not needing strict adherence to details or any single definition of canon. StarSpray writes:

I like to remain pretty canon compliant, except when I deliberately set out to write a canon-divergent AU. Much of my fic falls into the gaps that Tolkien didn’t write about, so canon is the foundation and the frame that I’m building off of in my fics. I never want to throw it out completely, even when writing about Elves in the modern day, because that takes away what drew me into the fandom in the first place.

For many respondents, the anchoring element of the canon is not plot or even character but theme: both Tolkien's themes and the themes of the fanwork. To the latter, one participant writes: "Generally when creating fanworks, I choose from among the versions of canon that I think most closely fit the themes I want to convey. One easy example is when Amrod dies; I have used and will use both the version in the published Silmarillion and the "burned at Losgar" version, depending on what the themes of my story need."

For another participant, canon is defined, at least in part, by the coherent themes that run through the multiple and contradictory versions of the texts:

I like to think of themes and how my writing can reflect those themes. I look at various drafts and see what similarities lie between them, and what is said and unsaid, what lies in the margins of the drafts that I can coax out. It's important to me to consider how the drafts work together, even if they seem to contradict on the surface. For instance, Maglor's fate shifts a lot between drafts but there is always that strong undercurrent of lament, loss, and grief, but also hope, uncertainty, and obscurity associated with the sea, so when I write about Maglor, I think of how his character ties back to those ideas, even if his fate changes in drafts. Ultimately, I decide on what I want to do based on the themes I pick up on from comparing drafts. To me, what is canon is the consistent themes throughout the work, and I write based on those.

Rowan Henry writes of what he calls "the heart of the stories"—the themes that form the backbone of the legendarium—and a desire to remain true to those, even while defying canon in other regards:

I use the "canon" for inspiration and for framework. I attempt to adhere to things like timelines when relevant (and clear), for example. But I tend to use a fairly transformative approach to canon in general, and I like to deliberately flout my perceptions of authorial intent ("writing fics that would make JRRT roll over in his grave"), especially in areas where my views and Tolkien's likely diverge. But I remain moved by the heart of the stories, of hope and friendship and value for the natural world, and in those ways I try to remain somewhat true to the spirit of the "canon."

Along similar lines, another respondent wrote that maintaining the "emotional truth" of a fanwork can cause her to treat canon more liberally:

As someone who can get quite pernickety about what Tolkien exactly says somewhere in some draft, when that question is considered on its own, I don't take quite the same approach in writing fanworks. I suppose that compared to some other writers and artists I am still quite canon-oriented in that it does really matter to me personally at various stages of writing what "canon" says and so things like a river flowing the wrong way on the map can create real problems for me that I may well try to solve. On the other hand, at some point the story itself and its emotional truth has to win and I will write it as it needs to be, while often commenting on any liberties taken in the notes (this is partly for myself, but partly also for the more detail-oriented among my readers). I suppose some kinds of canonical facts are also less important to me, temperamentally or emotionally; sometimes I am aware of this as I write, sometimes I only notice later.

This response also includes another element that surfaced throughout responses to how participants used canon in creating fanworks: the perceived need to mark canon divergence. "Canon is the foundation for everything I create for the fandom," wrote another respondent, "but I'm not afraid to diverge from it. When at all possible, though, I keep that divergence deliberate and mark it as such." I found myself curious about this impulse. It seems to reflect the importance of canon within the Tolkien fanworks community. Even when deviating from canon, fanworks creators sometimes feel the need to document that divergence. Perhaps, too, this practice has its roots in the fandom's history, where canon "errors" were harshly treated on some sites and in some communities, leading creators to poke fun at their fanworks where the notes were longer than the work itself.

Similarly, some respondents identified canon as important so that they could know when they were choosing not to follow it. "Even when I'm writing canon divergence," wrote one respondent, "I like to have a grounding in canon so I know what I'm changing and what's staying the same. My own preferred personal canon is what I mainly use for my fanworks, but sometimes I'll deviate from that, too!" Chrissystriped expressed a similar use of canon: "I often pick and choose from different versions of canon and like to use obscure things from [the History of Middle-earth], if it fits the fic. I often write things that are consciously not-canon, but I like to know if there is canon for what I'm going to write, even if only so I can decide to ignore it."

Again reiterating the importance of canon within this community are responses from creators who defy canon as a means of engaging with it. Daniel Stride notes that he doesn't "consciously conflict with the 'facts' of canon. Representing them in a different light is much more interesting." SkyEventide's response also emphasizes the importance of canon to her, even as she uses it as a vehicle for evaluating and analyzing that same canon:

I stick to canon (or, as per previous answer, text as written) as much as possible, AND as much as I like. As possible, because if I know that something is elsewhere contradicted, or stated, then it's likely I'll bend my fanwork to that. However, it's possible that I don't like what's textual. Then I try to deconstruct it, challenge it, or work with it and interrogate it. In short, I'm here for the sandbox I was given. Whether I use the sand to build castles or start kicking it around with a vengeance is my prerogative, but I don't do as if the sand weren't there at all.

Another respondent, an artist, speaks of canon as "loose restrictions" that allow for building beyond the canon with a particular purpose in mind. In this case, their purpose is representing a more diverse cast of characters in Middle-earth:

When I was in early high school, I used to draw portraits of the characters according to popular fanart with little thought about canon. But now, my focus lies upon exploring what canon doesn’t describe; expanding upon the few things Tolkien wrote about the appearances of certain characters and peoples. I really want to go back to drawing his characters because I want to contribute illustrations that are more expansive than the typical "fantasy" look (huge thanks to the other artists who do this already). There’s so much wiggle room within canon for me to explore—and so much contempt for the Default White High Fantasy aesthetic people love to ascribe to Middle-earth.

The majority of respondents who fell somewhere between canon compliance and canon liberality expressed some degree of tension in how they used canon, often valuing canon even as they leveraged that canon to circumvent it. The use of the canon itself as a mode of questioning the canon demonstrates the centrality of the texts, what they say, and what they mean to most Tolkien fanworks creators.

Twisting the Box: Canon-Compliance

"Twisting my ideas to fit the canon is fun …"

~ Anérea

Fans who identified as canon-compliant were often similar. Rarely did they express that they valued to-the-letter adherence to what Tolkien wrote without deeper consideration of what those texts signify and how they function as a foundation for further creative, transformative works. Interestingly, not a single respondent indicated that it was important to them to follow Tolkien's canon as far as adhering to his religious values and morality, nor did any respondents equate canon compliance with respect for Tolkien. Historically, there have been fanworks communities and individual fans who do both. Part of this is selection bias—the SWG does not ascribe to either belief—but I wonder if the lack of such responses can be explained by shifting values in the fandom.

For many canon-compliant fans, following the canon is part of the challenge—and therefore the fun—of creating Tolkien-based fanworks. "I stick to canon as much as possible," one respondent explained, "and I work in elements of the broader body of his drafts and work where it has elements I enjoy (such as the existence of Fëanor's half-sisters). For me, part of the fun of fanworks is working within the frame of canon--it's more of a challenge than just making things up myself, but there's fun in that!"

There is a stereotype of canon compliance as a joyless, follow-the-dots approach to creating fanworks. (This is reflected in the broader fan studies scholarship as well, where fans who flout canon are often portrayed as a creative, freewheeling community that exists alongside the staid, "curative" fans who spend the time they could be writing stories to argue about population statistics and character hair colors.) Part of this is fandom history, where some sites harbored fans who would rampage through, correcting and disputing authors' interpretations of canon (often through a moral or religious lens, as noted above). However, I would point out that the previous respondent mentions the word fun twice and challenge once: clearly not all fans who highly value canonicity do so to wield it as a bludgeon. (Canon as a gatekeeping tool is discussed below.)

Idrils Scribe describes a similar enjoyment in making the many pieces of canon fit together into a fanwork:

I try to stay as close to canon as I can in my fanfiction. In case of contradictions or inconsistencies I pick the option that appeals to me, or that fits the story most conveniently. If something is left vague I see it as an invitation to fill it in with my own take. Personally I enjoy the challenge of operating within the parameters set by Tolkien, and I almost never feel a need to create an [alternate universe] by contradicting elements [Tolkien] was clear and consistent about.

Anérea depicts canon compliance as a choice—and challenge—rather than an imperative: "Sticking to canon for me is more of an interesting creative challenge than a have-to. Twisting my ideas to fit the canon is fun, as is twisting canon to fit my ideas! I'll happily use whatever obscure tidbits suit my purposes." Her approach hearkens back to the previous section, where respondents who fell between canon compliance and canon liberality often described the canon in terms that suggested malleability and use of the canon itself as a tool to interrogate and stretch the boundaries of the canon.

Some respondents who create canon-compliant fanworks describe a creative process that includes a large amount of research. In some cases, this is to ensure canon compliance. As one respondent writes:

I only write canon-compliant fic with rigorously researched and verified canonicity. To accomplish this, I make use of a multi-tiered canon ranking system, with works finished and published by Tolkien within his lifetime at the top and early drafts, one-off details, and Myths Transformed at the bottom. I have no interest in going against canon, focusing on alternative narratives that contradict canon, or anything except "turning the world Tolkien wrote into someplace you could imagine living in".

Canon here is leveraged to create a believable world. Creators who describe research as part of the process of producing canon-compliant fanworks also identify it as an enjoyable process. One respondent depicts a "taxing but enjoyable exercise":

I very much enjoy consulting Tolkien's works while I write my fanworks. As I wrote before, I write fanworks about The Lord of the Rings trilogy. I do a lot of research when I write, which occupies me for a long time. I love pursuing accuracy (or something that comes close to accuracy as far as fiction goes), so I like to stick close to what I consider canon. I even like to mimic Tolkien's writing and dialogue style, as it feels crucial to the world and characters he created. It becomes a taxing but enjoyable exercise for me.

Polutropos describes a research process that is far more than refreshing her memory on facts (though that is a part of it too), but is itself a creative exercise. Again, the idea of using canon details as building blocks when creating a believable world arises:

When I have a particular character, relationship, period, and/or place from Tolkien's legendarium that I want to write about, I gather together and refresh myself on canon facts about them before wading too deep into writing. During writing, I often refer back to Tolkien's works to see if he ever wrote anything that would contradict a direction I intend to go. For the most part, I find all the contradictions in Tolkien's writings inspire me to think creatively about how the "culture" he created could have originated all of those different versions.

As noted above, fan studies scholarship has often positioned fanworks creation as an act that defies the authority of the original creator, i.e., the canon. In some cases, this leads to the idea that defying canon is essential to using fanworks as a mode of questioning and "repairing"1 the canon to address harmful stereotypes and inequities. The history of the Tolkien fanworks fandom does not help dispel the equivalency between "canonicity" and "intolerance"; in the 2021 Tolkien Society seminar "Tolkien and Diversity," I made the case that canon has been weaponized in the fandom's past to prevent fans from producing fanworks and discussing topics that explored the racism, sexism, and homophobia inherent in Tolkien's world. While again acknowledging the likely selection bias in the fans who answered a call for responses here on the SWG, an organization that has worked to welcome those fanworks and discussions, it is interesting that this approach to canon in fanworks was entirely absent from the responses. No one acknowledged using canon to uphold Tolkien's morality, a common pretense for excluding fanworks about women and LGBTQIA+ characters. In fact, Independence1776 emphasizes the importance of canon to her fanworks while dismissing Tolkien's morality as any part of the canon:

I write Middle-earth fic because I care about the world as-written. I strive to stick close to the facts and details as Tolkien established them; authorial intent matters to me. That doesn't mean I think M-e fic needs to abide by Tolkien's supposed morals (I flatly do not, and also think none of us can actually know them). I'm not perfect and I know I've made mistakes because I don't have an encyclopedic knowledge of the Legendarium. But my fics need to work within Middle-earth; if I can't do that, I may as well write the fics as original fiction instead so I can do my own thing.

Gideon Cooper likewise sees the canon as essential to maintaining a coherent world. However, they do not find that this bars exploration of the "problematic foundations" of the canon either:

So in essence to me it IS important to hold as closely to the canon we are given as seems feasible, because it kind of gives me a framework to build off of if that makes sense. The world IS cohesive and much of the attitudes, actions, and events within it feed off each other into more and more complex ideas and narratives so I like to buy into them as much as possible, whilst acknowledging and addressing the inherent problematic foundations that all of it possesses.

Ultimately, fans who self-identified as canon-compliant differed from fans who were more permissive in allowing themselves to disregard canon only in the degree to which they adhered to canon. Philosophically, the groups were very similar. Canon imposed boundaries that were interesting and fun to work among, offered the raw materials for building a believable Secondary World, and provided the means for questioning and sometimes challenging the implications of the texts.

"Sailing Off": Canon Liberality

"I happily grab … a blended canon, which I then usually triumphantly sail off with into alternate reality/universe stories …"

~ Ithiliana/Robin Anne Reid

Far fewer fanworks creators indicated that they didn't care much for canon at all, and even in those instances, I struggled with whether those responses belonged as "canon-liberal" examples or in the earlier section on the vast expanse between this designation and "canon compliance." Many of the responses I'm including here do show an interest in "following canon." Egg's response is one example of this. She writes, "I like to have my cake and eat it, too. I use the canon as an anchoring to consistency within the rules, histories, and worlds of Arda. I then use the canon to stay as in-character as possible to keep readers in sync with what I write, but deviate as desired for the pure sake of wish fulfillment!" Here, canon provides useful consistency but is not more important than the creator's desire for how the fanwork should take shape.

Another respondent similarly cited "truth" in a creative work as more important than adhering to canon: "I don't really care about canon in my fanworks, to be honest. I have my own interpretation of the characters and if someone else finds that interpretation non-canonical, I don't care. I do tend to refer more to the characterization of the books and slightly model my writing style after Tolkien's, but it's not a priority. I just take what I like and what rings true to me and run with it."

Other participants enjoyed writing in obscure areas of the legendarium or alternate universe (AU) fanworks, which lend themselves to creating outside the bounds of canon. Shadow writes:

Within this setting, I mostly try to keep canon consistent, but I'm not too bothered if I don't.

Especially in the Second Age. Aside from Númenor, we know comparatively little, so if the things I make up aren't always consistent with what we Do know, I'm fine with that. I also write a lot of AUs, and some of them don't really lend themselves to consistency with canon either way.

My speciality (if you can call it that) in the First Age is the Lords of Gondolin, mainly Rog and Salgant. We know super little about them, most of which is found in The Fall of Gondolin, which obviously contains multiple versions of the same story. Here, I like to pick and choose parts for my story and combine across multiple versions.

Ithiliana/Robin Anne Reid similarly expresses a love for alternative universe fanworks and also addresses the use of canon by some fans to limit interpretations under the pretense of "respecting Tolkien":

I happily grab from Tolkien's published fiction (almost entirely LotR) and from Peter Jackson's films, so a blended canon, which I then usually triumphantly sail off with into alternate reality/universe stories (I LOVE AUs). I'm all in for Emerson's "a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds" snark in the sense that I just don't care because just about everything I love about Tolkien's world as I see it would probably horrify the poor man. But he released his books out into the wild (and, following his death, his legally designated heirs and executors ditto), which means that within the bounds of fair use (NOT ripping off and profiting from his work), I can do anything I want. I dislike the hagiographic tone of some fans and scholars who seem to emphasize "respect" in a way that comes across as them speaking for "Tolkien" and demanding limitations that suit their ideologies and preferences, and my response to that attitude is, fuck, no.

In short, canon-liberal creators express a variety of reasons for discarding canon partly or entirely. Sometimes, personal preference and truth need to reign supreme in a creative work. In other instances, the fragmentary and contradictory nature of Tolkien's texts requires a degree of inventiveness that belies canon compliance. Then there is love for the alternate universe and other "canon deviations" that can expand the legendarium creatively.

Personal Canon: Defining and Using

The responses discussed above reflect last month's discussion of defining canon: It's complicated. Every creator has a different approach, and many creators don't always stick to just one. Terms like verse and head canon add to the complexity of which texts (and interpretations) a particular creator regards as a store of factual information for a fanwork, and which they do not.

A few respondents alluded to personal canon: Whether their definition of canon and the texts they used as canon remained consistent across multiple fanworks. I've selected three responses that, like the definition and application of canon, show that there is no universal approach among creators. Cuarthol writes that she does have a personal canon that she tends to use in her fanworks: "I do like to explore variations on Tokien's legendarium, but I do have a certain version of events I broadly prefer and stick to in most of my writing, which tends towards canon-compliance (for some version of canon) and gap-filler stories."

Lyra occupies a more middle ground where personal canon is concerned: "I generally try to keep my work consistent with some form of canon (as in, compatible with something Tolkien said somewhere) but not necessarily always the same idea of it. I may use multiple versions of canon occasionally (and I'm certainly willing to interact with multiple versions), but I tend to have a preferred version that I mostly stick to."

Marta offer yet another perspective, where a consistent "personal canon" isn't necessary at all:

I really don't feel any compulsion to make my personal canon consistent across stories. Whatever works for that particular work, and whatever I don't think I need to lay out for my reader, is what matters. But then I write short stories more so there's less assuming people are with you for more than a single story in that world. If I was building longer works or a more obviously interconnected series, I might feel differently.

Again, this specific issue of personal canon shows the myriad ways that creators engaged in making Tolkien-based fanworks interact with and use the texts to make fanworks.

"The Gatekeepers": Canon and "Canaticism"

"Too often I find canon used as a bludgeon by the gatekeepers."

~ Robinson Ensz

It's impossible to talk about canon and Tolkien fandom history without broaching the topic of canaticism (a term coined by the Tolkien fanfiction writer Rous in the 2000s). As earlier responses and discussions implied, the subject of Tolkien's canon has not always been a neutral one, particularly in the fanworks community where the desire—reflected in many of the responses above—to reveal a deeper truth or reflect the creator's experience can create a tension with the "facts" of canon. As the responses above show, not all creators prioritize "textual details" and "truth" and "wish fulfillment" in the same way.

Not surprisingly, fans with different expectations around the concept of "canon" didn't always peacefully meld when they found themselves sharing online spaces. As Robinson Ensz explains:

I do not believe in the upholding of a strict canon of anything. Were I pushed to give an answer, I would say only that which Tolkien himself was alive to publish should ever be considered anything within strict bounds—though not necessarily "THE canon." I think canon is what we want it to be; the texts that shape our Middle-earth. Too often I find canon used as a bludgeon by the gatekeepers. This is something I wish I could abolish entirely.