Mapping Arda, Part II: Travels through Beleriand by Anérea, Dawn Felagund

Posted on 1 December 2023; updated on 25 November 2024

This article is part of the newsletter column Tolkien Fanartics.

This is the fashion of the lands into which the Noldor came, in the north of the western regions of Middle-earth, in the ancient days.1

Beleriand is a land of legend. By the time the narrators of The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings pen their stories, Beleriand has been lost beneath the sea, its people and places relegated to nostalgic imaginings. Perhaps for this reason, mapping Beleriand—and all of the various forms of information that maps can convey—holds a lot of appeal, both for Tolkien himself and the fans who follow in trying to understand the legendary realm that ensnared his imagination for most of his life.

Tolkien spent a lot of time mapping the lands of Beleriand, and although there were a few versions, and more than a few discrepancies, he provided us with a very clear view of this part of his world. This nonetheless still leaves plenty of scope for fans to expand on, be they imaginative pictorial reinterpretations or schematic infographics. As the fan-created maps in this collection demonstrate, fans have plumbed the canon and used all manner of details—supplemented by the work of other fans and scholars and their own creative interpretations—to develop maps representing the geography of Beleriand.

Lay of the Land

In reading The Silmarillion, the contours of the land shape the story. Thangorodrim pierces the sky, Gondolin huddles amid its ring of mountains, and Ossiriand stretches forward from the Blue Mountains, carved by its seven rivers. As characters and battles traverse these landscapes, readers are invited to visualise the lay of the land and how its geography provides opportunities and obstacles and shapes the history that takes place upon it.

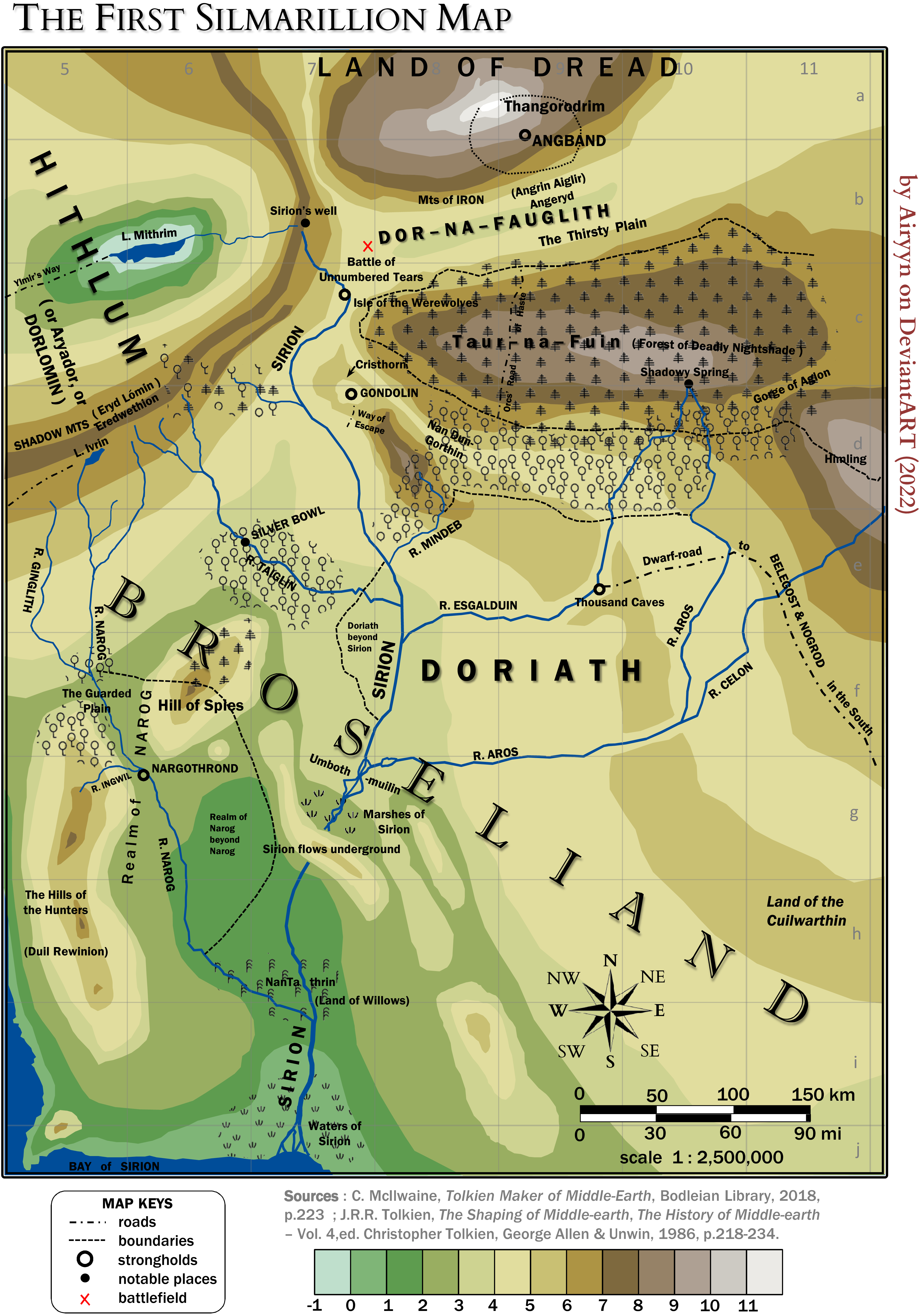

Although Tolkien's First "Silmarillion" Map, drawn in 1930 or earlier, depicted “Broseliand”—later to become Beleriand—many of the places so familiar in The Silmarillion were already present and in the same locations. Unlike his later maps though, this was drawn with contour lines. Airyyn re-rendered it with a hypsometric scale in order to provide a better understanding of the landscape:

In the original map, there is a big problem concerning contour lines in the area between Doriath and Taur-na-Fuin; to avoid this, I had to create “canyons” for the rivers Aros and Esgalduin. The scale is based on the Second "Silmarillion" Map due to the consistency of the grid squares in the later map. We also see clearly that Lake Mithrim is, like the Dead Sea in Israel, below sea level.

The First "Silmarillion" Map also situated Gondolin in the southwestern foothills of the Dorthonion plateau on a massif occupying Dimbar, all of which later vanished when it became encircled by the more imposing Echoriath, a continuation of the Ered Gorgoroth.

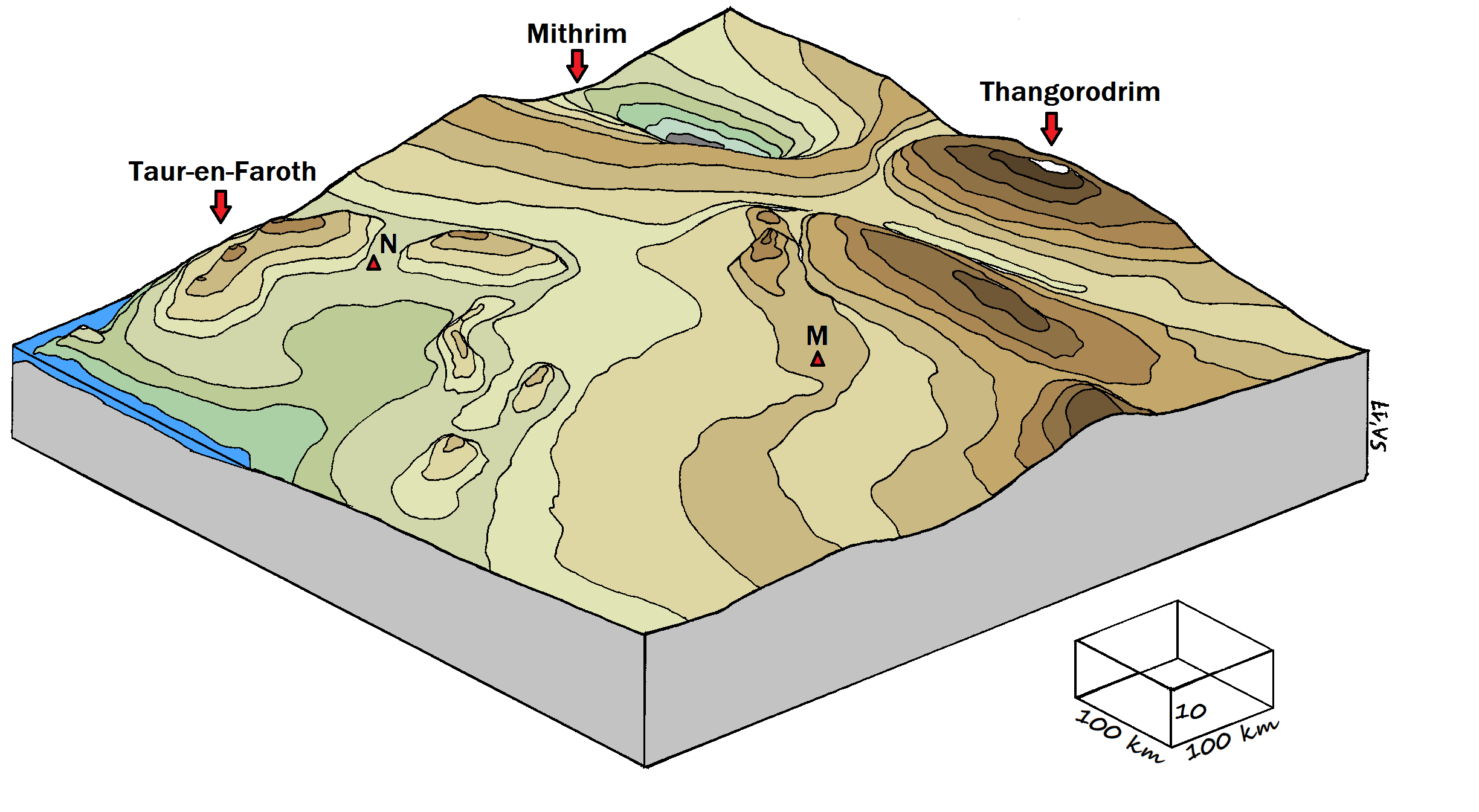

Airyyn then went on to create an axonometric view, providing a clear visual of the fall of the land. (Hydrography and places of interest have been removed. The locations of Nargothrond and Menegroth are shown by the triangles marked N and M respectively.) Recalling the process of creating this map, Airyyn writes:

I remember that the creation of this map was complicated. Firstly I digitised contour lines and collected points from them. Then I rendered in Scilab (a free clone of Matlab) a 3D surface from the contour lines, and I recopied it by hand. Finally, the sketch was scanned and coloured with the software Paint.2

Airyyn's topographical maps render those details we know from reading The Silmarillion in a fresh, visual form where it becomes possible to imagine climbing the dizzying heights of Thangorodrim or Taur-na-Fuin, sliding into the icy waters of Mithrim with the landscape towering around you, and tracing Beleriand's many rivers as they rush from the mountains to the sea.

Picturing Journeys

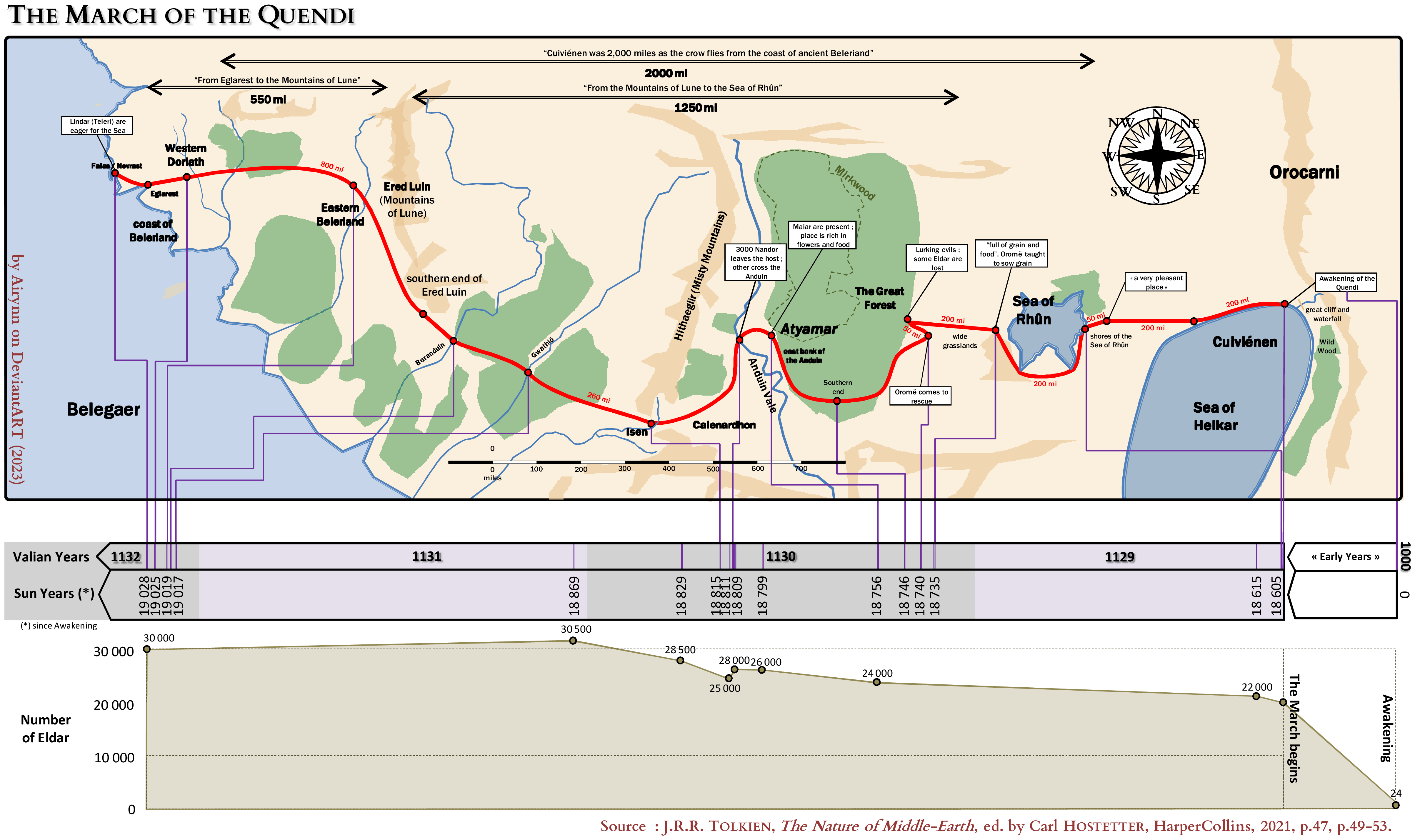

Airyyn’s penchant for data has led to the creation of a collection of maps that visualise geographically elements of the tales of The Silmarillion. Like the lay of the land, the migration of peoples and the marshalling of armies is a key element to the history of the First Age. Tolkien leaves it up to the readers to imagine the perils of the quest from Cuiviénen or the wearisome trek of armies across the wilderness, but Airyyn presents these tales in a cartographic form, often blending the narrative and numeric.

Unlike some of us who barely managed a glance at the numerical data presented in The Nature of Middle-earth before tuning out, Airyyn was in their element, delving into the data and ultimately writing an essay on the ageing of Elves and another (as yet unpublished) about the generational schemes. While writing these, Airyyn was struck with how the journey of the Elves from Cuiviénen to the Falas could be represented in a similar way to Charles Minard’s Figurative Map of the successive losses in men of the French Army in the Russian campaign 1812–1813. Using Fonstad's Atlas of Middle-earth as a general reference, Airyyn plotted the journey with significant points mentioned in the text, combining it with a timeline and a graph of the population growth to provide a graphic representation of the numbers.

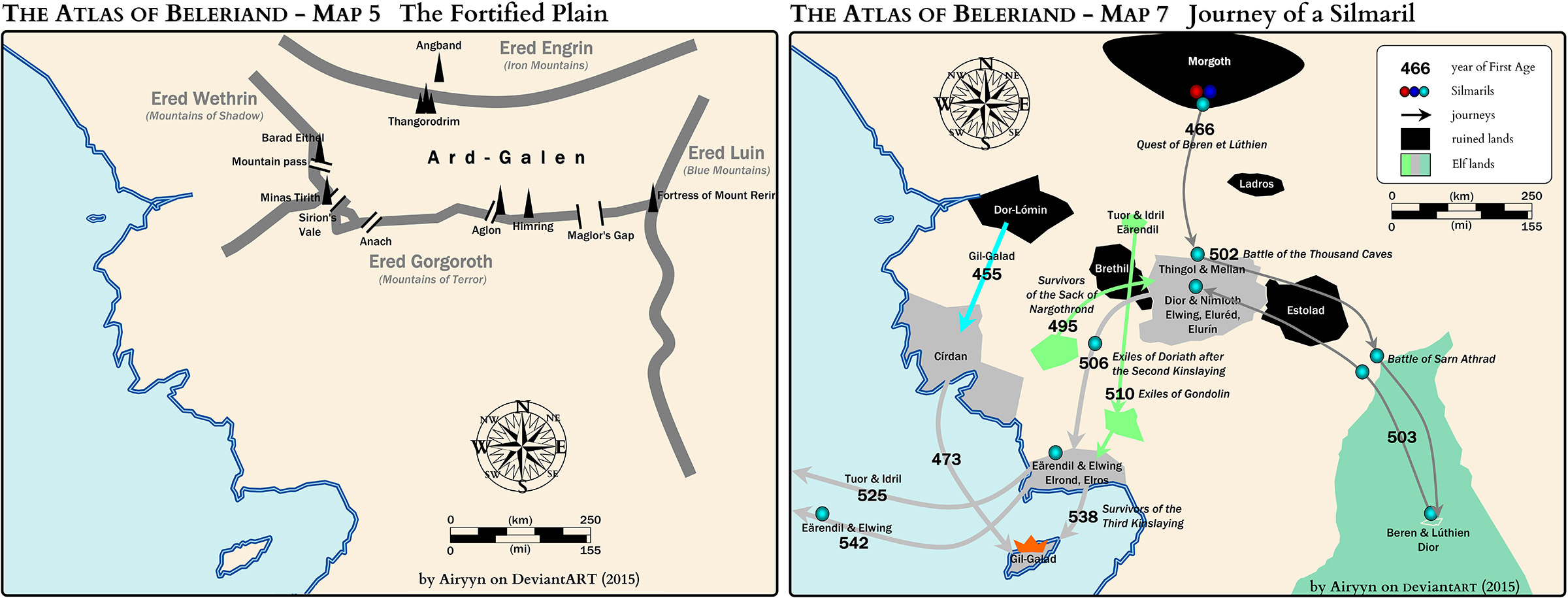

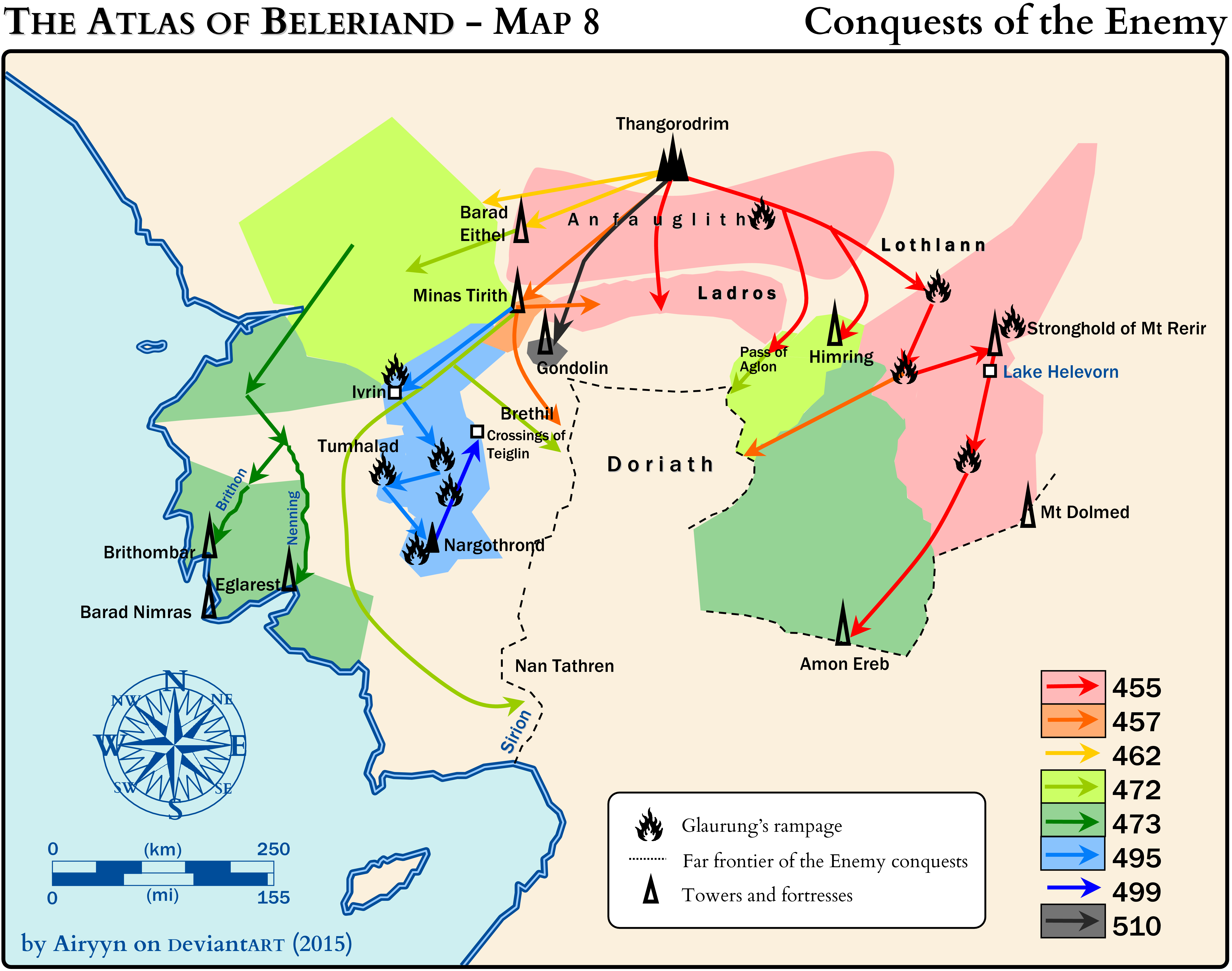

Airyyn's Atlas géopolitique du Beleriand—a collection of ten infographic maps, excerpted below—brings together the people and geography of Beleriand, showing political divisions, migrations, and the outcomes of battles. Airyyn has done the work of showing how Tolkien's two modes of representing Beleriand—historical and cartographic—overlap to produce the stories of The Silmarillion.

During the Long Peace, Morgoth was besieged within his fortress of Angband. This map shows the few passes that pierce the mountains surrounding Ard-galen and the location of the fortresses guarding them. The realms to the south experienced fewer incursions as a result of this protection, allowing realms like Nargothrond and Doriath to thrive. During the Battle of Sudden Flame, these few passes became the only escape routes for those living on the plain.

The First Age is an era of migrations. First, the Noldor move in and colonise their realms, likely shifting the homelands of the indigenous Elves as a result, followed by the migration of the Edain into Beleriand. It is the tumultuous years after the Nirnaeth Arnoediad, however, where large groups of people move due to political violence, as well as key journeys of individual players in the history of the First Age. Journey of a Silmaril depicts the major journeys undertaken towards the end of the First Age, after Beren and Lúthien steal the Silmaril from Morgoth’s crown.

Likewise, while the territories of the Elves remained relatively stable during the long years of the Siege of Angband, the Battle of Sudden Flame heralded major changes in the status quo. Here, we see movements of the enemy into the territories of Beleriand, signalling not only a political shift but sparking the major migrations that we see at the end of the First Age. The map Conquests of the Enemy shows how, in relatively few years, Melkor's forces gained a foothold across much of Beleriand.

Through the Eyes of a Child

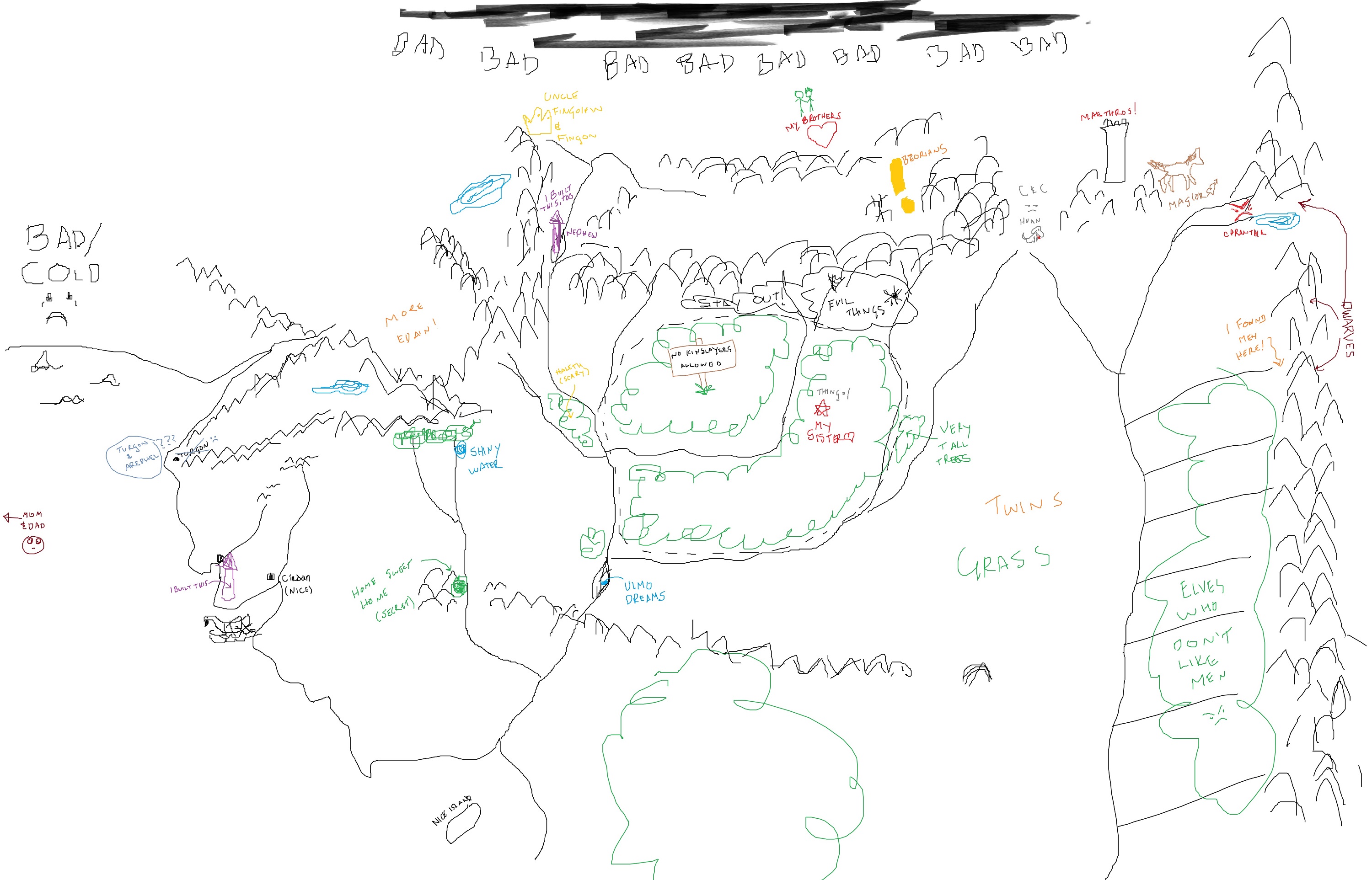

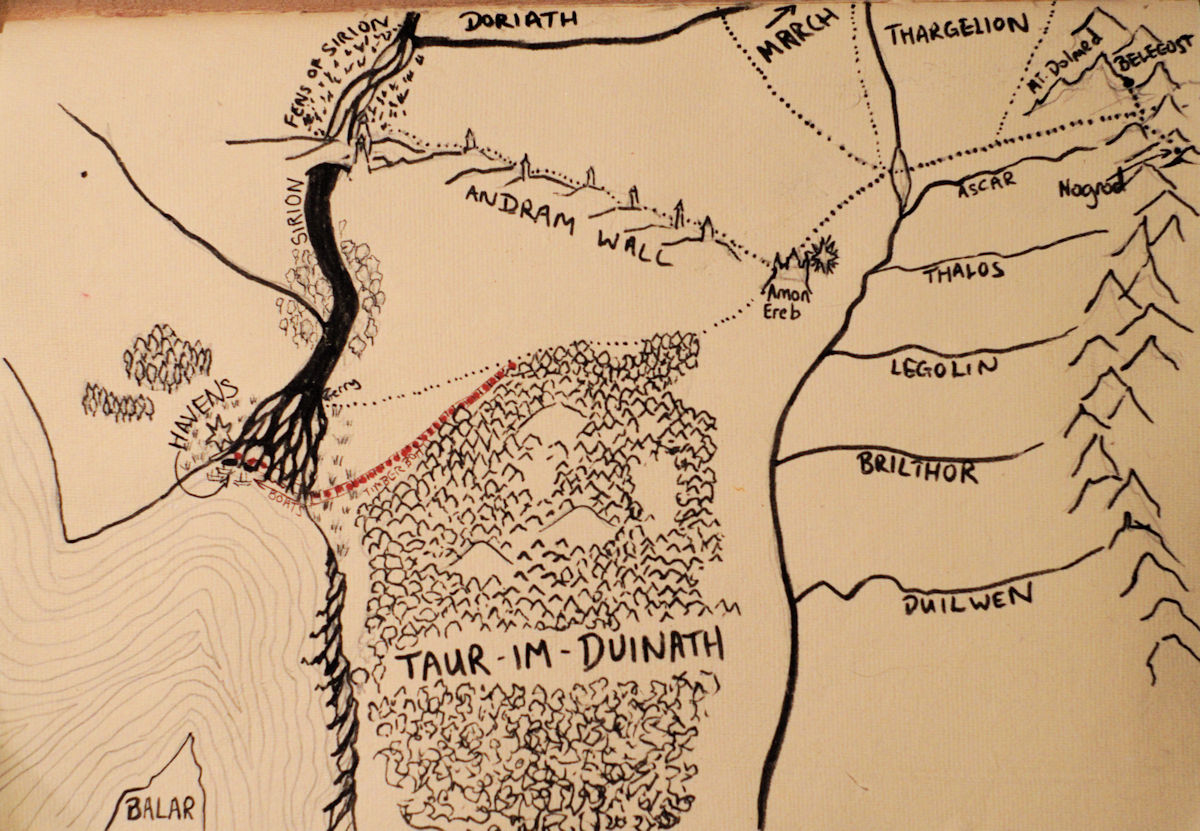

Geography can feel very neutral. A mountain rises no matter who the feet climbing it belong to, and the waters of a river quench the thirst of Orcs as easily as Elves. Cuarthol's map, however, shows how cartography can capture point of view. For the SWG 30-Day Character Study challenge she chose to explore Finrod. When she saw that the prompt for Day 28 was "a location familiar to your character", she realised it meant either attempting to draw Nargothrond or, considering how Finrod galavanted all over the place, a map that effectively summarised events in Beleriand from Finrod's point of view.

"I don't remember why I started making silly little notes," Cuarthol writes, "but once I started I was all in. Perhaps a bit of a 'there be dragons here' ode to old maps with notes about what might be in places unexplored, but in this case it was notes about what was really there. The whole thing came out like a child's drawing which was a nice change from trying to do something that looked more finished, and it reminded me of why coloring (even 'virtually') is such a nice break from adulthood."

Although Cuarthol used a mouse in MS Paint to draw the map, she says we can "imagine little child Finrod on his stomach with a stack of crayons, kicking his feet as he fills in all the important landmarks." The result is an adorable map that evokes the joy of creating maps that I (and I'm guessing many of us) used to enjoy as kids.

Threads of a Story

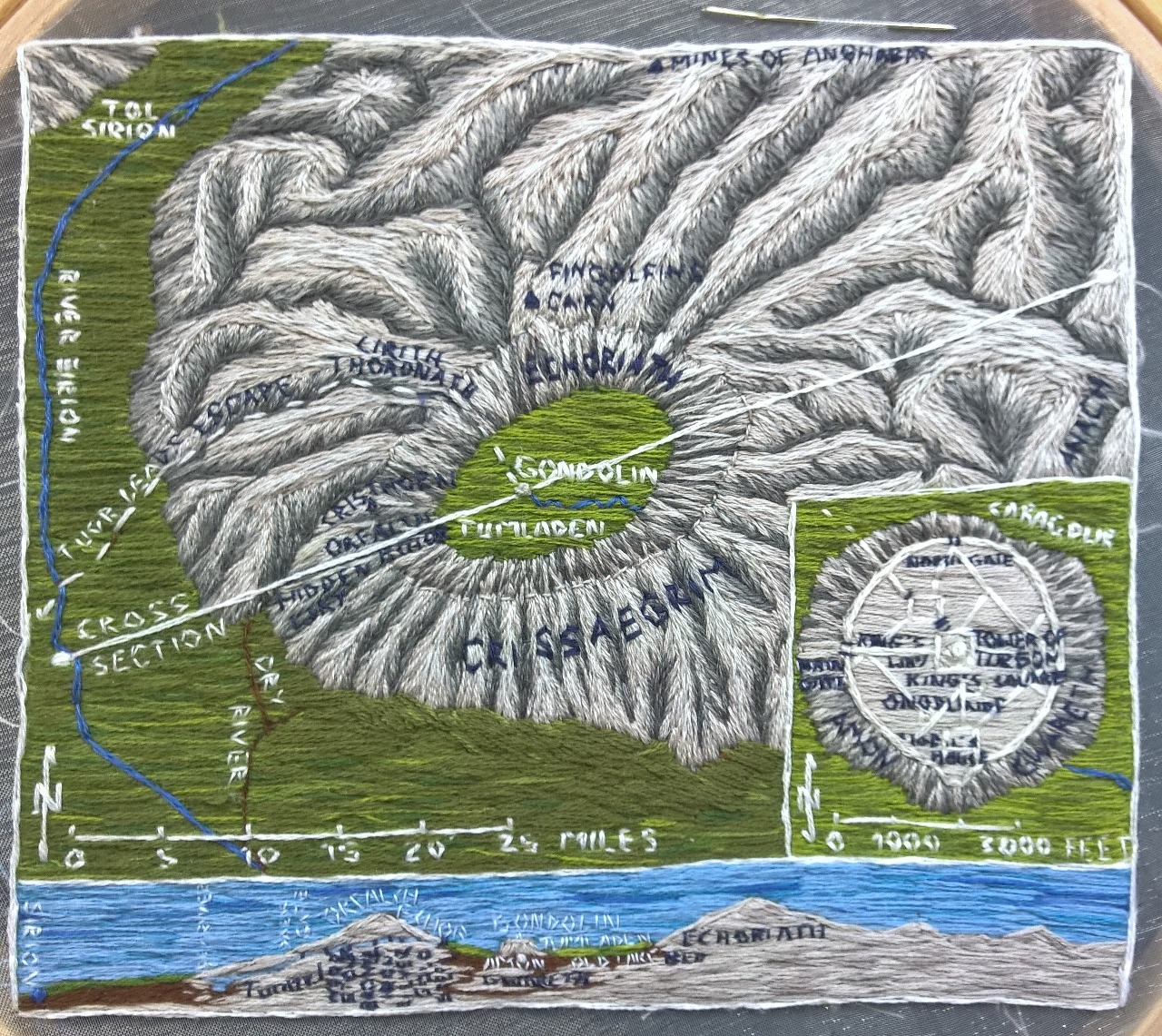

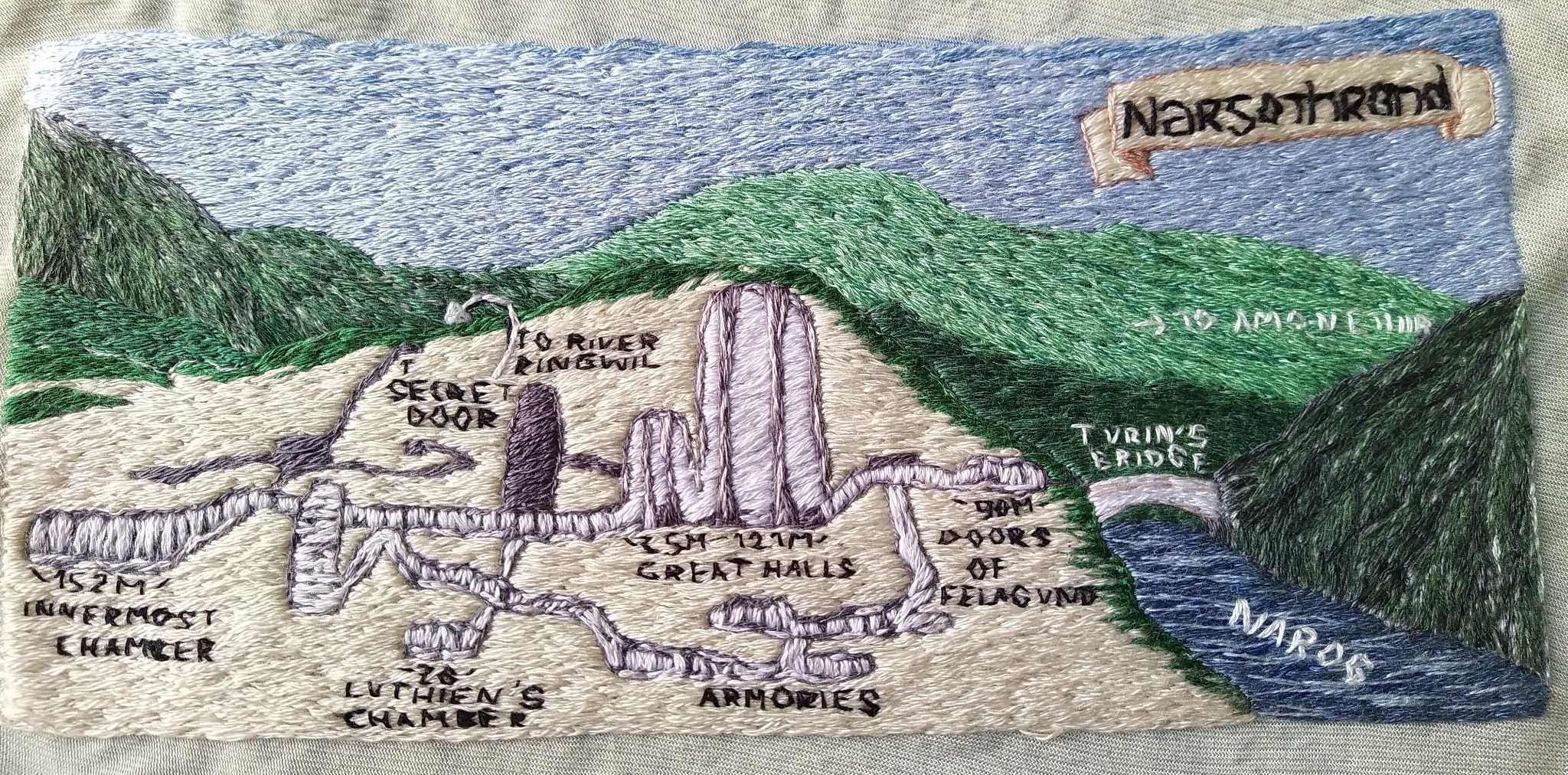

Evoking the work of Míriel and Vairë, iaearcanvennamar has embroidered maps of the two hidden cities of Beleriand (as well as Númenor which will feature in the next article in this series.)

Gondolin is her favourite city and story in The Silmarillion (after the Akallabêth). The technique she used could be called needle painting. Starting with an outline drawn on the fabric with water-soluble pen, she then stitched the outline and filled in the colours with coloured threads. "The mountains were a pain," she recalls; "I first did them in brown colours, didn’t like it and stitched over them in grey." The result is a unique rendering of Tumladen, the Amon Gwareth, and the Encircling Mountains.

Another favourite of hers is Finrod and the process for making the map of Nargothrond was similar: "I based it on the map in [The Atlas of Middle-earth] but changed the perspective a bit because I was not in the mood for mountains/hills, I haven’t recovered from Gondolin yet."

Many of us are hypercritical of our own work, with the perceived flaws standing out, yet although she says she doesn't like her lettering, it's clear a lot of time and patience has gone into the stitching, and the subtle shading in the hills and the river are particularly beautiful.

The stitched outline of Beleriand has been sitting in a frame for a few years, just waiting for the right time and motivation to take hold. Iaearcanvennamar envisions a future for her work: "I guess I have a grand plan ... to embroider a map of Beleriand in detail and stitch that to something else and add some detail maps like Gondolin and Nargothrond around it."

Pictorial Beleriand

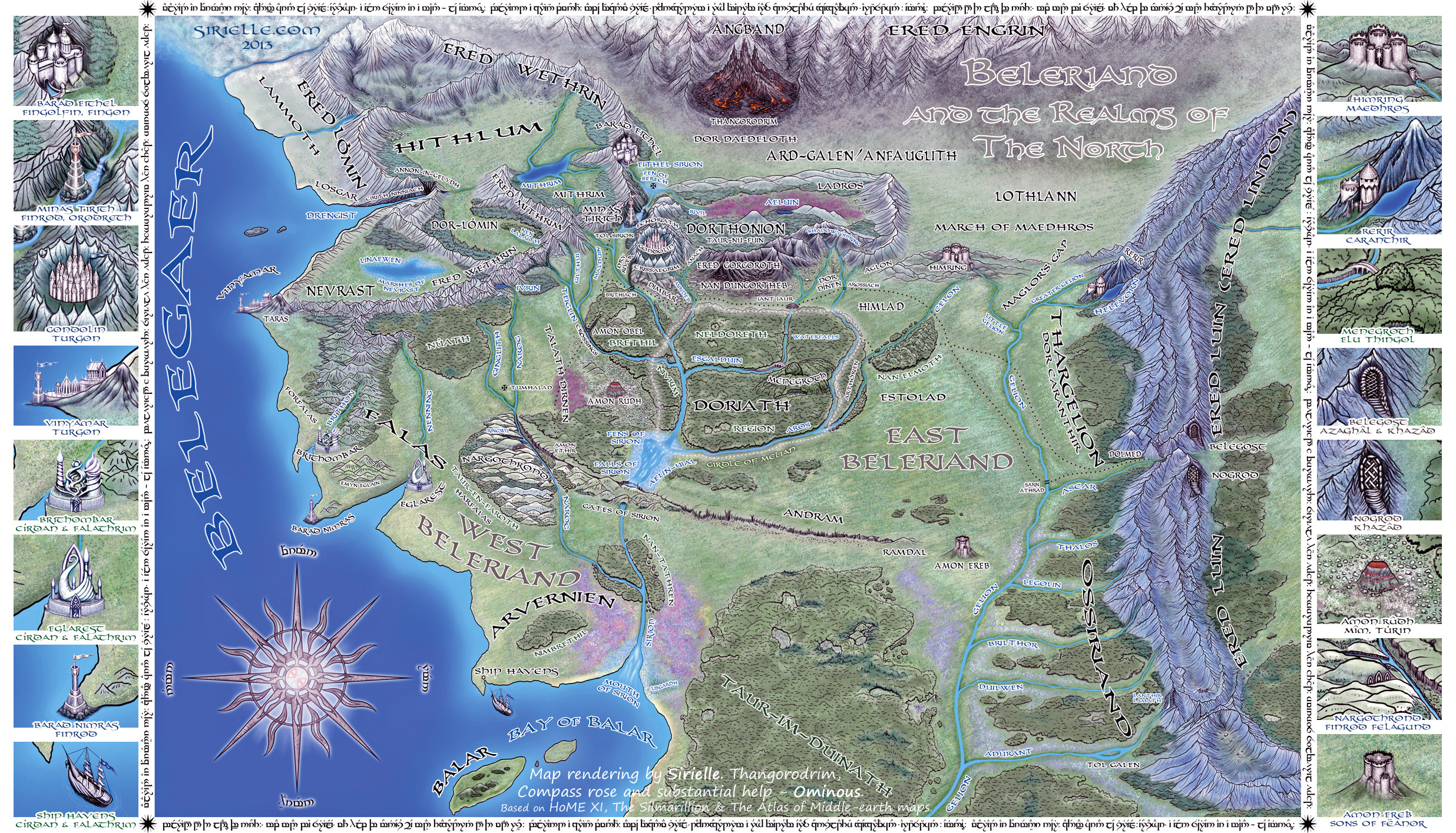

Maps are a fanwork like any other: beginning upon a foundation—often the Silmarillion map found in the back of the book—and using other canon details to build up from it. The maps made by Sirielle (Karolina) show the level of research required to expand upon Tolkien's maps — she teamed up with her fellow "loremasters", Ominously and M.L., to dig up details in History of Middle-earth Volume XI: The War of the Jewels in addition to The Silmarillion and Karen Wynn Fonstad's The Atlas of Middle-earth.

While the shape of the continent, the configuration of mountains, forests and rivers, and the location of settlements by necessity follows Tolkien's map, Karolina's Beleriand is enlivened through colourful pictorial representations of the terrain and symbolic drawings conveying the unique character of each city and fortress, resulting in a distinctively unique and detailed artwork.

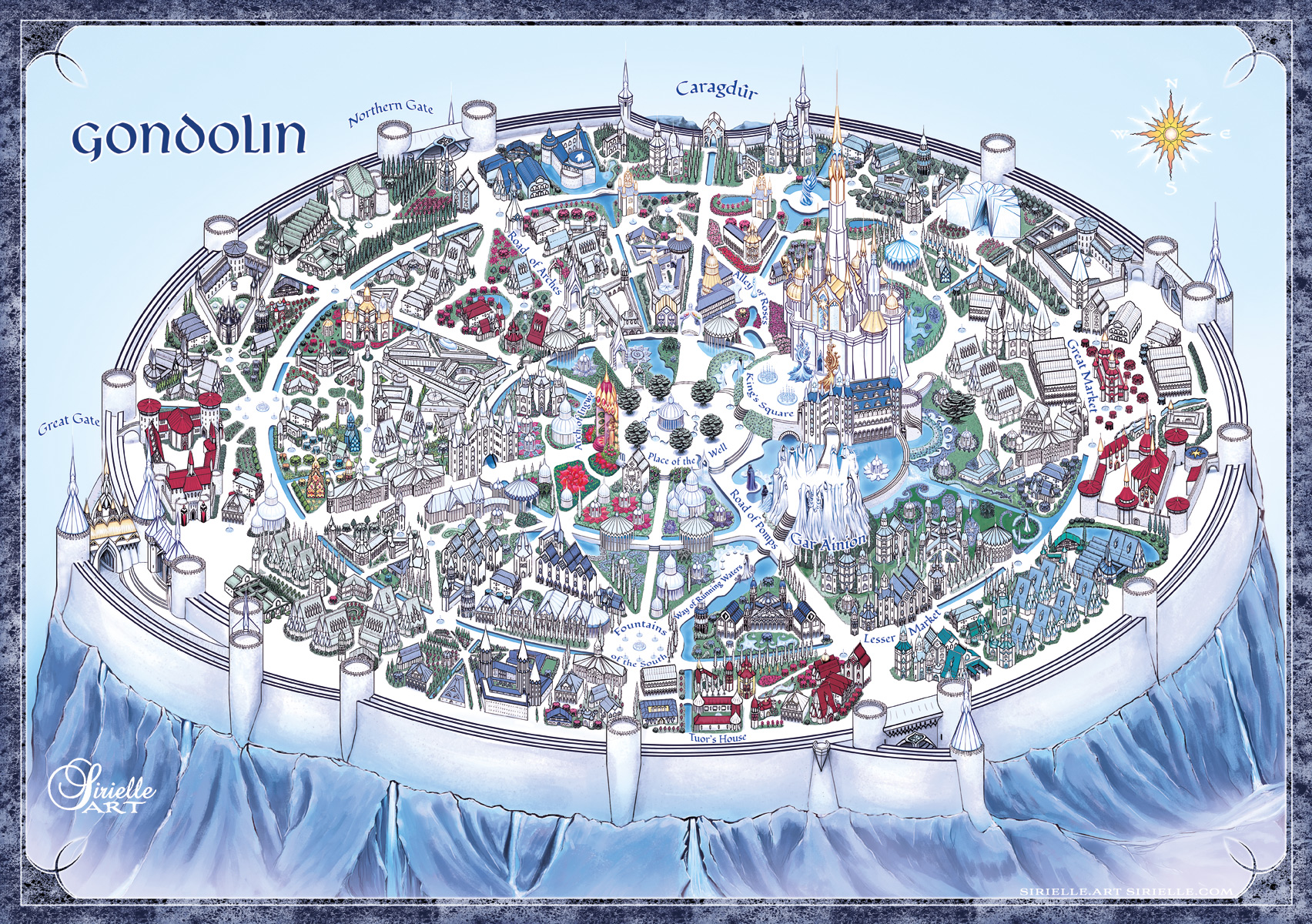

When she began sketching her plan of Gondolin, she initially referred to The Atlas of Middle-earth, however it was ultimately the descriptions by the in-universe loremasters in The Fall of Gondolin (The Book of Lost Tales II) that guided her choices. As so frequently happens in the tales from The Silmarillion, there were some contradictions in the text where they had to choose between variants, or occasionally construct something new.

The statues and buildings depicted in Karolina’s plan of Gondolin are again symbolic rather than accurate representations drawn to scale, to avoid the places of note becoming lost in a sea of tiny houses: "At first I started with much smaller buildings and more streets, but abandoned that idea, enlarged the buildings and continued from there.” Her buildings are so beautiful so fortunately for us she went on to enlarge and redraw the whole map in greater detail, so we get to view such delights as the two trees, Belthil and Glingal, the statues of the Valar at Gair Ainion, as well as statues of Finwë, Ingwë, and others dear to the Elves of Gondolin.

She also created two different labelled versions: one naming the streets and points of interest (shown above) and another detailing the location of the Twelve Houses"

In my interpretation there is a fortress for every of the twelve houses within the city walls, and the houses serve as military centers (with armories, training rooms, barracks etc.). Fortresses are placed on the outer parts of the city and a few in the center—should citizens need to hide behind walls there is always a hideout in the neighborhood. The placement itself is mostly a guess. The closest to description in The Fall of Gondolin is the House of the Harp, which was placed north of the Lesser Market.

I can recommend reading Sirielle’s “Notes for Tolkien Geeks” where she describes some of the contradictions encountered in the texts and explains how she decided on her ultimate choices for the map.

Drowning a Continent: The War of Wrath

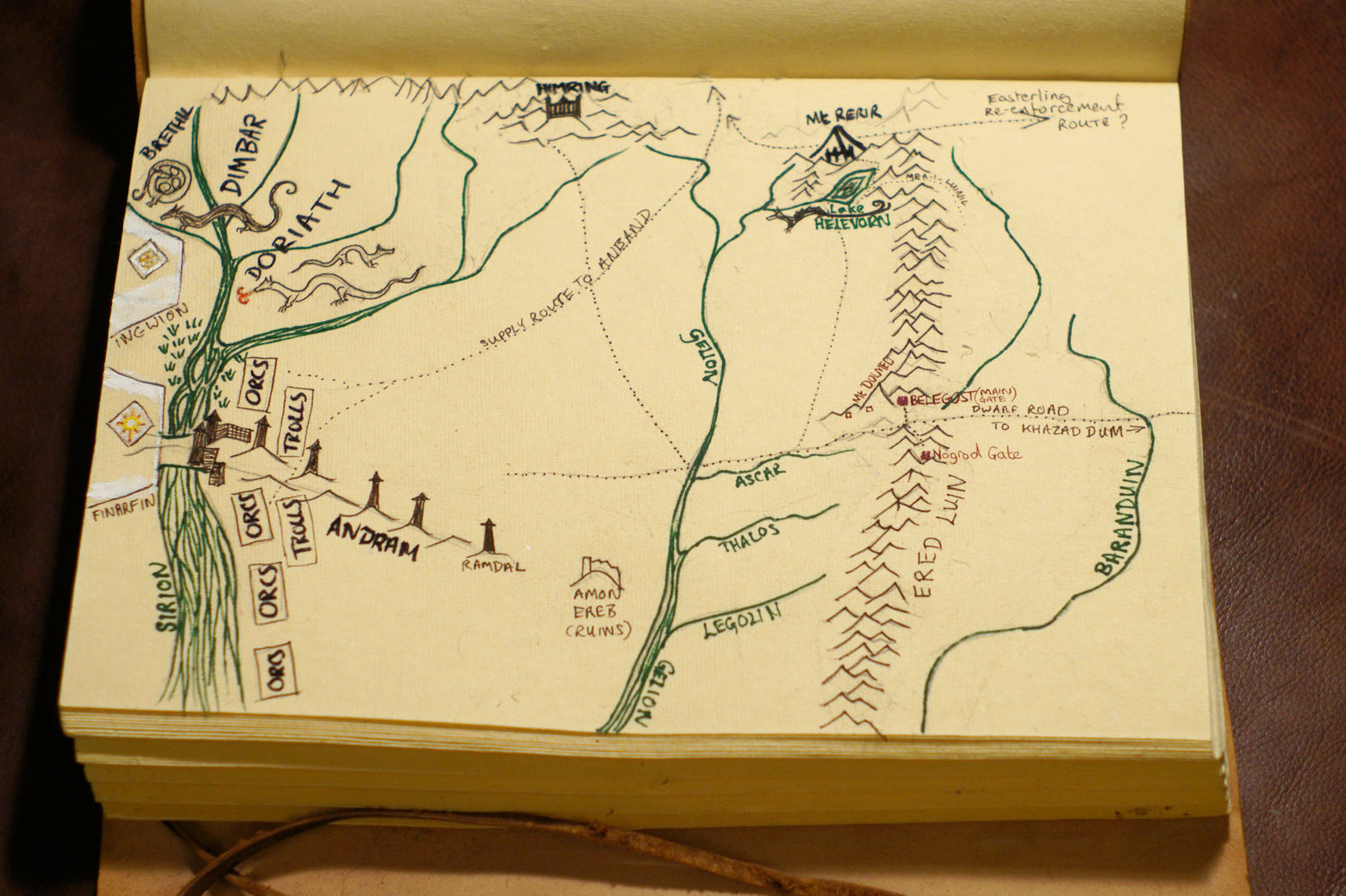

While working on her fanfic Quenta Narquelion, bunn followed Tolkien's advice about starting a story with a map:

The reason for creating the maps was that I wanted to write a story with a number of episodes set during the War of Wrath, and I felt that if I was going to tell that story, I needed to know at least roughly where and when things happened.

Drawing on the precious few scraps of information about the War of Wrath, including a vague mention in The War of the Jewels of a battle in Tasarinan and a difficulty crossing the river Sirion, as well as the descriptions about the strategic layout of the land in the chapter "Of Beleriand and Its Realms", she created two helpful aids to visualising events, which are at the same time aesthetic works of art.

Bunn ascertained that during this time:

[t]he forces of Valinor are on the west bank of the Sirion, which is too wide to be crossed onto the east bank, occupied by Morgoth's forces, except via the land bridge formed by the western end of the Andram Wall. The remnant Fëanorian force is at Belegost in the Ered Luin. Himring is occupied by the Enemy at this point, and probably so is Mount Rerir. The best military route to Angband is across the Sirion and north between Himring and Mount Rerir (Maglor's Gap).

Of course, there is another pass not shown to the northwest of this map [Beleriand] but it’s very narrow, ends in fens, and as Finrod found in Dagor Bragollach, is not easy to force.

The drowning of the entire continent of Beleriand is described in one single sentence,3 which leaves it wonderfully wide open to interpretation.

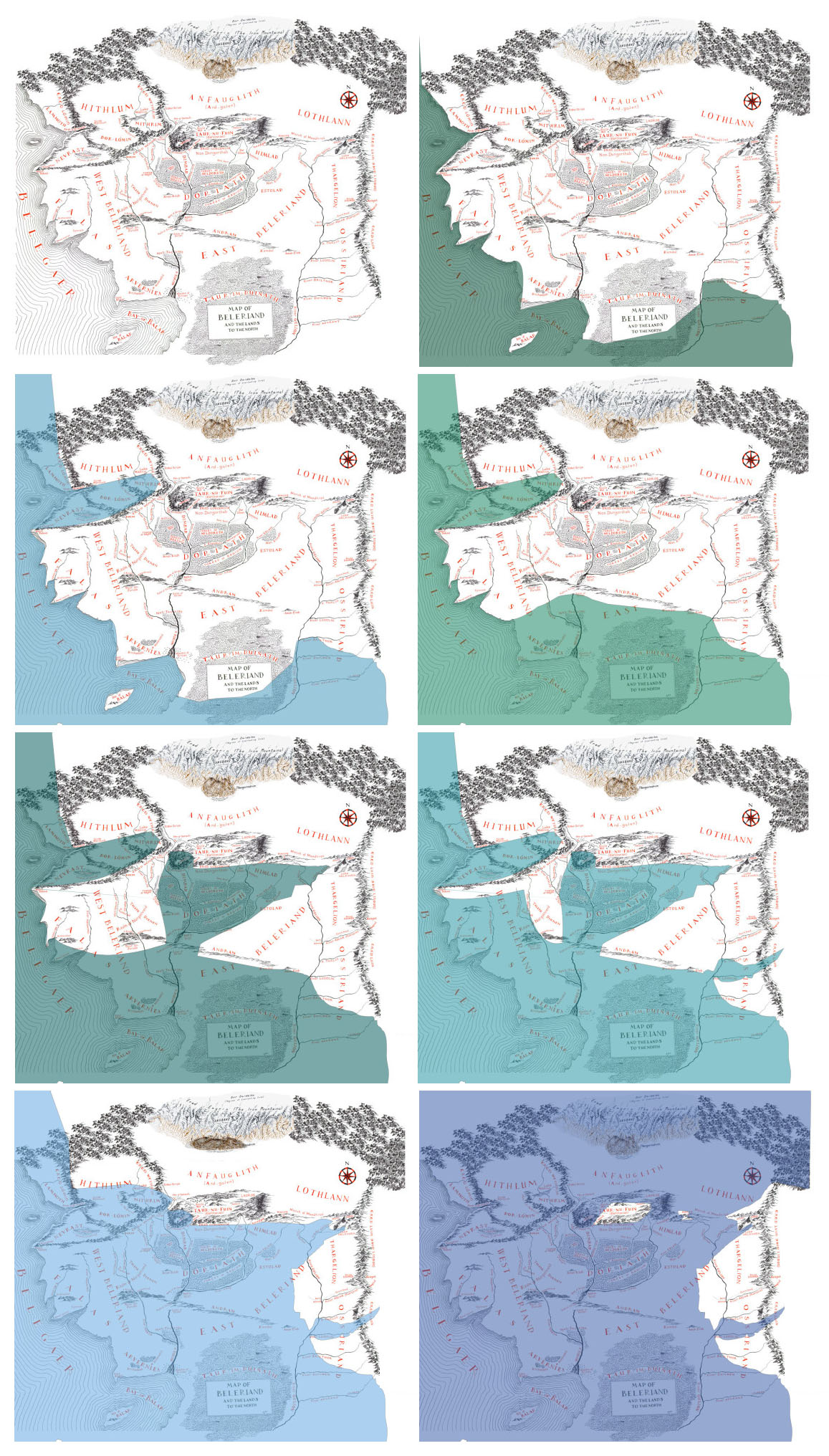

For her "War of Wrath" series, Bunn assumed that "a lot of the land was magically sunk, that the sinking was done in a number of battles, rather than all at once (because the war took forty-three years, but quite a few people did survive it) and that places where there are big mountains before might now be fathoms deep." In order to visualise the events over this time period, she created a series of maps along with a timeline using the first and last days as stated in The War of the Jewels, and making up the rest.

From top to bottom, left to right:

545 : the Host of the Valar arrive in Middle Earth. Noldor land at Mouths of Sirion, Vanyar land at Eglarest.

559: Attack from the east on Bay of Balar, counterattack takes out lower Gelion

563: Balrog attacks from Nevrast repulsed

565: Giant flood magic on River Sirion

577 Ulmo takes action on dragon infestation in Doriath & Brethil

583 Ered Luin, Nogrod, Belegost, attacked by fleeing Balrog. Gulf of Lune created

587 : Victory in Middle Earth

590 : Melkor thrust through the Doors of Night into the Everlasting Darkness, Angband area collapses.

East and West: Connecting Beleriand and Eriador

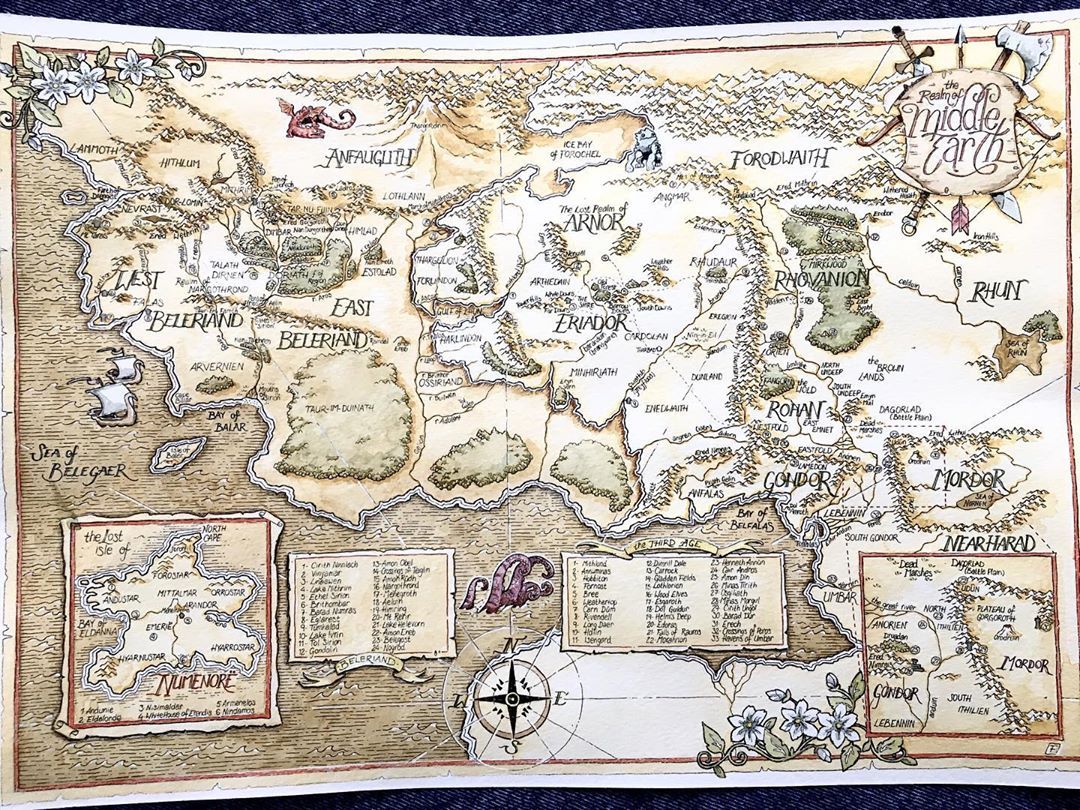

Like many fans, Fitolop longed to visualise how Beleriand connected to the lands east of the Ered Luin. Many of us have studied the maps in The Lord of the Rings and imagined the seas receding and the Silmarillion map slowly revealed. Since Tolkien didn’t provide us with a map of those lands before the world was made round, it’s been up to fans to figure out how best to integrate the First and Third Age Middle-earth maps.

An autodidact illustrator, Fitolop took up the challenge, adapting the style of the original maps and hand-lettering the labels which, along with the decorative drawings, give the map an authentic air. He says: “Then the project went further by adding the Númenor and Gondor panels, and finally the specific sites panels that made the massive map easier to read. I saved the original and tried watercolors on a copy, hoping to give it an old-map style.” He also says that if he were to remake it, he would go for an even simpler style, with more cartoony trees and mountains; however, for me, it is the classic style it’s been rendered in that holds its charm.

Conclusion to Part II

Whether Beleriand as seen by a child or data-powered computer-generated topographies, what these maps have in common is their power to combine scholarship, creativity, and artistic skill to expand upon the sometimes scant details Tolkien gave us about the lost lands of Beleriand. These maps are both products of and springboards to imagination: creative works in their own right yet opening the door too to further fanworks exploring how the peoples of Beleriand experienced the physical landscapes that formed their homes. They often introduce a human element that can be forgotten when working with just the original Silmarillion map. These are places where people lived and that people moved across. A mountain that offers protection to one becomes a barrier to escape for another; the shadows of a nearby wood can provoke a sense of safety, terror, or wonder. The work of the cartographers building on Tolkien's maps bring new perspectives to bear on the lands and people of a lost, legendary world.

There are a lot more lovely fan maps of Beleriand than I could possibly include in one article, and I didn't always manage to contact the artists, so here are links to a few others:

An interactive map of Beleriand by Emil Johansson, creator of the LOTR Project, with overlays showing locations of points of interest and paths tracking the journeys of Turin, Tuor and Beren.

A fun Arda Rail routemap of Beleriand by Korrigandu

Panorama des cartographes de la Terre du Milieu, an impressive list of Middle-earth maps throughout the Ages, by Airyyn.

Notes

- The Silmarillion, "Of Beleriand and Its Realms".

- First published in black & white in Fées, navigateurs et autres miscellanées en Terre du Milieu, Le Dragon de Brume, 2017.

- "For so great was the fury of those adversaries that the northern regions of the western world were rent asunder, and the sea roared in through many chasms, and there was confusion and great noise; and rivers perished or found new paths, and the valleys were upheaved and the hills trod down." (The Silmarillion, "Of the Voyage of Eärendil and the War of Wrath.")

Read Mapping Arda Part I: Terraforming and Part III: The Second Age

A big thank you, Dawn, for…

A big thank you, Dawn, for rescuing me when my "wordability" went south, ensuring this article actually got finished, in style!

This is so VERY cool, Anérea…

This is so VERY cool, Anérea! Thanks so much!

:)

I'm so very glad you think so! Thank you so much for letting me know!

More maps!

Part II of this article is as astonishing as the previous section. Every map used here to illustrate what can be done with the information available is unique and wonderful. The Young Finrod map is especially sweet. 🧡

I'm so pleased you've…

I'm so pleased you've enjoyed this as well! I've been so enchanted with discovering the variety and creativity of fan made Tolkien maps, and seeing how others envision the magic words he gave us sparks so many fresh ideas.

Sorry it took me so long to…

Sorry it took me so long to finish this but awesome! I love how people have both interpreted but also the many ways the maps have been rendered. That embroidery is spectacular! And I love Bunn's slow destruction of Beleriand series. <3

:)

Thank you, first of all for sharing your own delightful interpretation and rendering! And thanks for the lovely comment!,♡

I've been meaning to read…

I've been meaning to read this series for AGES. What a well-researched and laid-out collection of maps. You've definitely piqued my interest in the storytelling potentials of geography.

♡

Yay! In that case my job is done! I love these marvellous maps with thier unique detail and inspiration, and I'm so glad you appreciateand feel inspired by them too!