The Easterling Hostages in Middle-earth and Their Parallels in Welsh Medieval History by MirienSilowende

Posted on 18 August 2022; updated on 18 August 2022

This article is part of the newsletter column A Sense of History.

The Easterlings are a people that are fairly shrouded in mystery, in their origins at least. As they were seen to fight in the Battle of the Pelennor Fields against Gondor in TA 3019, offering their strength of arms to Sauron, many would say they were the bad ones. And to an extent they would be right, as they were longstanding enemies of Gondor. Whether they were right to be enemies of Gondor or not is a different question.

The Easterlings were a mixture of peoples, from Men who decided not to move to Númenor after the War of Wrath, to Men who left Númenor to populate the Havens of Umbar and settle there, and even later, including Men from Gondor itself who tired of the politics of the city. Their origin is largely unknown but there were mentions of them from some point in the Second Age. However, there are Easterlings mentioned in the First Age, such as Bór and Ulfang, who fought against the Alliance at Nirnaeth Arnoediad.

This article looks at a specific reign a little later, though, from the Third Age 1050, when a King called Ciryaher took the throne of Gondor. He inherited the throne during an age of war, when Umbar was particularly strong. But the ships of Gondor were stronger. In TA 1050 he took his fleet and crushed Umbar. After his great victory he changed his name to Hyarmendacil, South-victor:

Ciryaher son of Ciryandil bided his time, and at last when he had gathered strength he came down from the north by sea and by land, and crossing the River Harnen his armies utterly defeated the Men of the Harad, and their kings were compelled to acknowledge the overlordship of Gondor (1050). Ciryaher then took the name of Hyarmendacil 'South-victor'.1

Now this was very typical for the highly skilled men of Gondor at this time, but Ciryaher, now Hyarmendacil, went a step further. He crushed the Easterlings in a bid to ensure they would not rise against him again, further consolidating his power as King of Gondor. And it worked. In his entire reign, nobody dared to stand against him. This brought Gondor a much-needed peace and, along with it, great prosperity:

In his day Gondor reached the summit of its power. The realm then extended north to the field of Celebrant and the southern eaves of Mirkwood; west to the Greyflood; east to the inland Sea of Rhûn; south to the River Harnen, and thence along the coast to the peninsula and haven of Umbar.

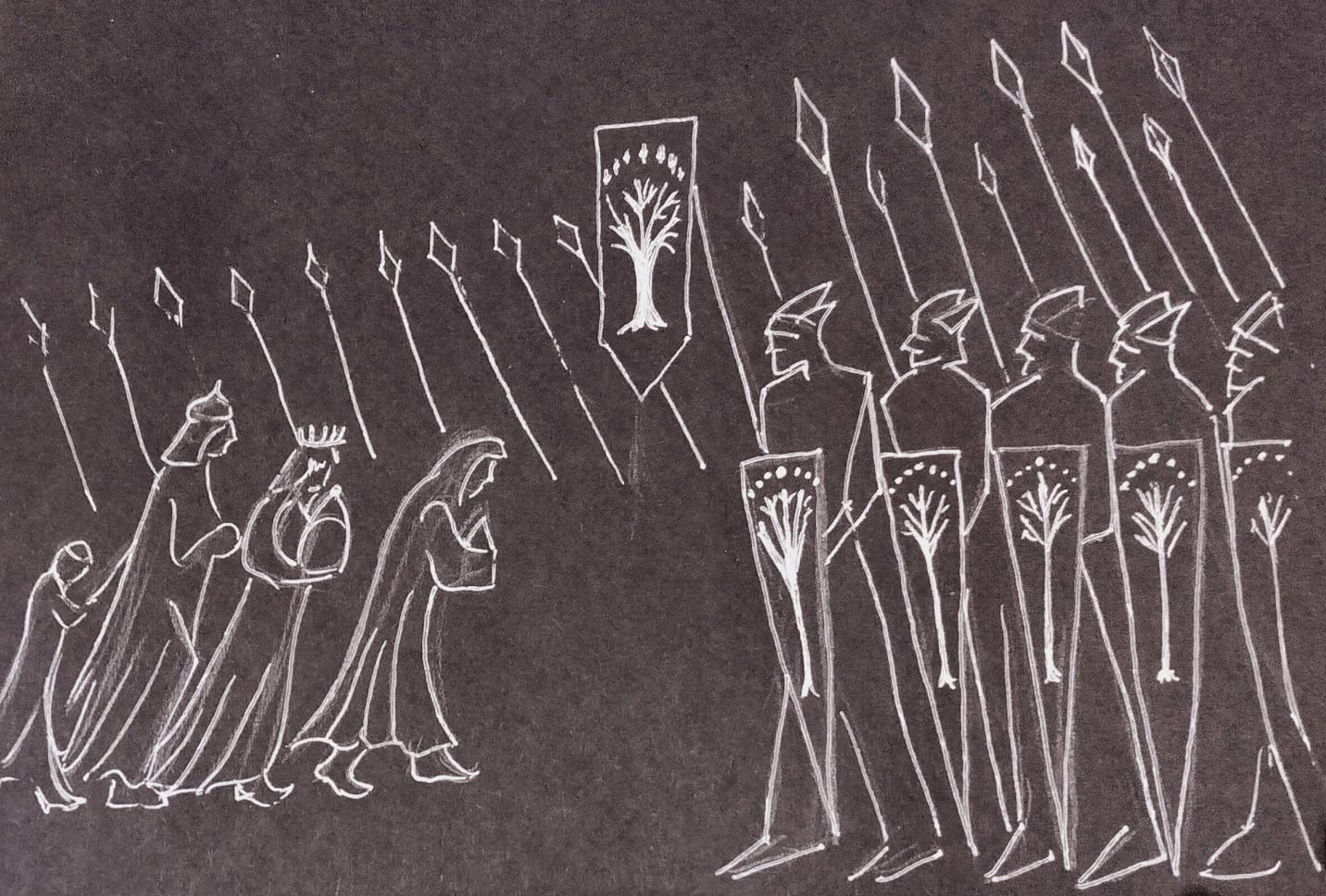

The men of the Vales of Anduin acknowledged its authority; and the Kings of Harad did homage to Gondor, and their sons lived as hostages in the court of its King.2

The men of the Vales of Anduin were the friends of Gondor, the Eotheod, who later became the Rohirrim. They were clearly valued by Hyarmendacil and were required to merely acknowledge his authority. The conquered Easterlings had more to do. They had to pay homage to Gondor, and their sons lived as hostages in the court of Gondor.

What did this mean in real terms? Paying homage meant more than just going to the court and pledging allegiance, but that was certainly part of it. It also meant paying a tribute, either with money or goods to show that they were vassals to the king. This kept the country poorer and less able to mobilise troops. It’s been a common tactic after wars for centuries and in fact was used even in the last century after the First World War.

Hyarmendacil also took hostages. The modern term of hostage usually conjures up ideas of a bank and guns and being kept as a bargaining chip for the FBI to rescue or similar, and in modern-day terms that certainly would be the case. The underlying meaning is the same, but the process was different.

The Easterlings were forced to give up their sons as surety to Gondor, which meant the Easterling princes were forced to live in the Gondorian court with high-ranking families in Gondor. They lived in uncertainty as they were indeed bargaining chips. And if the situation worsened, they would pay dearly.

If the Easterlings behaved, the Princes would survive. If they did not … then that would be a different story. But there was another, darker element to this tactic. As the sons were young and malleable, inevitably they would grow to have affection for their foster families, learning to speak the language of Gondor and adapting its habits.

When they reached manhood, Gondor could send them back as puppet Easterling princes who would surrender to the King’s will more easily. The Easterlings may have considered them to be cuckoos, returned to the nest, but not as they once were. This in turn would weaken the unity of the lands and the people.

There is a strong parallel to this story within history, and so I turn my focus now to the Plantagenets, a dynasty that stretched from France to England and even out towards the Middle East following successes in the Crusades. They began their reign in 1154. The Plantagenets were strong rulers with little mercy, and they were well known for using this tactic, securing hostages, usually young princes or the sons of noblemen, to secure the subjugation of the Welsh.

The Norman Kings of England had been working on taking control of Wales for some time, but they were troublesome to deal with, causing skirmishes and attacking castles. King Henry decided to start taking hostages and tributes as surety to stop the Welsh from starting more rebellions. In 1157 Owain of Gwynedd offered up hostages and a tribute to the king and he gave homage, meaning that he acknowledged Henry as his overlord. A year later, Rhys ab Gruffudd gave hostages in return for recognition of his status in Wales and more land. Owain gave homage again in 1163, offering fourteen hostages, four thousand oxen and three hundred horses.3

It was often perceived to be a political manoeuvre, something that everyone did but there were no consequences to it. The hostages may have disagreed, being put into a court where they did not understand the language, but they were not considered to be unsafe. They were treated fairly well and in fact some later secured places at court.

Things changed when King John ascended the throne and Llywellyn ab Iorweth was acknowledged as Prince of Gwynedd. He was an ambitious man, and while he did homage in a similar fashion to his ancestors, and even married an illegitimate daughter of King John, he planned to be more than just a nominal prince of Gwynedd. The resulting rebellions meant that he too was forced to give up thirty hostages and a promise of twenty thousand cattle, three thousand to be offered immediately, forty steed, and an annual render of falcons.4

It crippled the region and Llywellyn had no choice but to retaliate with military force. King John also retaliated, by executing the hostages. The game had changed and the stakes were so much higher; their own blood was at risk. Within a century, the strength of an independent Wales was in tatters and the Kings of England had total control.

Going back to Middle-earth, this shows us a snapshot of how it could have been for the Easterling princes. Hyarmendacil was a strong king who ruled his tributary areas with a fist of iron. Would he have baulked at killing hostages if the Easterlings had rebelled? It’s doubtful. This was a strong king who demanded total obedience from all the countries under his yoke.

And certainly Tolkien told us that they submitted to his rule: “The might of Hyarmendacil no enemy dared to contest during the remainder of his long reign. He was king for one hundred and thirty-four years, the longest reign but one of all the Line of Anarion.”5

It was certainly an effective tactic, but I would say a cruel one. Taking children as pawns to ensure a nation’s subjugation is a harsh way to rule, and it could, along with the being forced to pay tribute, be a reason why later there were still wars between the Easterlings and Gondor.

If Hyarmendacil had acted in a more cooperative, less colonial manner, then Sauron may not have been able to continue to manipulate the Easterlings as well as he did. The Wainrider attacks that weakened Gondor and the Battles at Celebrant and then later at the Pelennor Fields may never have come to happen. The Return of the King could have been an entirely different story.

Works Cited

- The Lord of the Rings, Appendix A, "Gondor and the Heirs of Anárion."

- Ibid.

- David Moore, The Welsh Wars of Independence (Gloucestershire: History Press Limited, 2007).

- Ibid.

- The Lord of the Rings, Appendix A, "Gondor and the Heirs of Anárion."

Easterlings as "other"

It had not occurred to me that these peoples would have included ex-Gondorians and Númenoreans as well as men who had stayed in Endor and were later conquered by Gondor. Making the further parallel of Gondor's Easterling hostages and England's Welsh hostages is eye-opening. The threat of death balanced against the disadvantage to the conquered country of assimilation / indoctrination is real.

Exactly, yes, they weren't…

Exactly, yes, they weren't as homogeneous as we think, I suspect. They were still distantly related. Yes the threat of death to control a country is an effective tactic. A cruel one though!

A sympathetic look at the…

A sympathetic look at the plight of those compelled to give hostages and the situation of the hostages themselves!

The Plantagenets and Wales make for a compelling parallel (although similar tactics had been used earlier).

That's absolutely true! The…

That's absolutely true! The Plantagenets certainly did not invent the tactic. But it did seem a similar theme and of course the Professor would have known about that situation, being so close to home geographically and academically.

I think the Easterlings do deserve some sympathy. I do think they were a bloodthirsty people, but I do think Gondor did not help itself.

Hostages as control

Really interesting article- I think I was aware but skipped over it in my mind and hadn't connected that with other musings about why the Easterlings were swayed by Sauron, apart from perhaps the historic link with Morgoth as you point out, with exceptions of course. The Romans did this big time as well of course and were perhaps the most effective users of hostage taking to control and 'civilise' their provinces/ colonies. The analysis of the Welsh Princes and Plantagenets is fascinating.

Thank you very much! I think…

Thank you very much! I think yes we see the Easterlings and think oh yes they did bad stuff - and they did, absolutely, but there's a lot of murky history lurking about in the closets of the Gondorian Kings. As you say, the Romans used this tactic to great success, it was a quick way to kneecap a strong warlike country. And the 'civilisation' followed very quickly. I'm a fan of the Welsh Princes and Plantagenets, and I think Tolkien with his background may have had them in mind when he wrote the Appendix. But of course we will never know! Thank you so much for commenting. I really appreciate it!