Never Mind the Dwarves by simon

Posted on 8 December 2023; updated on 17 January 2024

This article is part of the newsletter column A Sense of History.

Never Mind the Dwarves

March 8, 1939. A house in north Oxford. Occupied, but the man who lives here is abroad—he has gone north to deliver a lecture. Another person is on the grounds. Having entered through the gate, he stands in the garden by an open window, peering into the study. Not yet a burglar. His name is Peregrin Boffin and his face is a picture of enchantment. Boffin’s rapt gaze is caught by a stone that had appeared on the desk inside the room earlier that day. The stone looks round and captures his heart: an object of impossible beauty. A great desire has awoken within him to inspect this stone more closely. Weighed in the balance, Boffin awakes from his trance and steps through the window. Inside the room his eyes alight as his hands grasp the stone. Boffin holds it up to his eyes and, as he looks into it, he and the stone both vanish.

On that day when the stone in the room appeared and disappeared, Boffin had been watching the house for over a year. The man who lived in it was a friend of a friend, and some years back Boffin had attended a party in the man’s garden. Apparently, the man’s best friend (long dead) had once laid down a most peculiar rock garden, which the man had reconstructed by his own house. When he was done, he had invited the neighbourhood to a garden party where they could see it for what it was. Boffin would never forget that evening. He had felt queer the moment he arrived, and to the end of his days could not recall how, around midnight, he had found himself shoulder to shoulder with the Cambridge Professor of Anglo-Saxon pushing over the great stone at the entrance. Nor could he ever recollect without an eerie shiver his frantic polishing with his pocket handkerchief of the newly revealed underside of this tall tower of a now toppled stone as he joined a group of befuddled antiquarian enthusiasts searching the still muddy bottom for hidden inscriptions. All but three of the guests had engaged in similar antics, with a couple of emeritus professors and a visitor from Denmark even digging holes in the lawn. Afterwards the rumour circulated that the beer so liberally handed out had been spiked. But Boffin had always felt there was something more sinister behind the whole affair.

That might have been that, had it not been for a chance observation in late December 1937. Passing the man’s house as he walked home with his Christmas shopping, Boffin had seen the man stepping into his garden with a single, comfortable-looking and newly polished stone in his hands. Slowing his pace, Boffin watched as the man placed the stone carefully near the top of an already prepared mound next to the herb garden below the kitchen window, surveyed the view, and then stepped back into his house. The man was making a new rock garden! Stealthily, Boffin opened the garden gate, hid his shopping behind some bushes, and crept to the large bay window on the study. He saw that the man was now sitting at his desk, pen by his hand, but that the paper before him was blank. Silent under the eaves, Boffin had watched with wonder as a stone began to appear on the paper.

This is Boffin’s story. He began it, though other hands recorded it, and work still to preserve his legacy. We labour gladly on behalf of our society, the Fellowship of Unimaginative Friends. Today we meet on occasion, and when three or more are gathered the conversation is amicable, as we swap notes and compare theories on the great rock garden, until the conversation turns, as it does, to Boffin; then tempers simmer, factions form, and friends fall out. The sad fact is that nobody can say what happened to Boffin because, although we now have in our possession the stone that vanished him, none of us dare to look into it.

The Unimaginative Friends, of whom your humble scribe is one of the younger fellows, unofficially began as simply the friends of Boffin—the friends, that is, in The Green Dragon public house on that cold December evening in 1937 to whom he recounted the laying of the new stone he had witnessed earlier that day. That night it was merely received as a good story, sparking renewed discussion of that wild night when the rock garden had been vandalized some years earlier. But as luck would have it, one of the regulars was the postman, and the next morning, delivering a special letter to the man’s children, he struck up a conversation with the man about the new stone in his garden. Truth be told, the postman had not fully understood the explanation, in the giving of which, he reported, the man had become most animated. But he came away with the definite impression that he had neither forgotten nor forgiven the destruction of the old rock garden and had formed the idea of using his first stone to turn the tables on his guests!

Naturally, this set tongues wagging in the public house and beyond, for many corners of respectable Oxford had felt hot under the collar following the orgy of destruction at the former garden party, and did not wish to see such a disgraceful disturbance in their town again. Several of the guests from the old party now became regulars at The Green Dragon. Still embarrassed and a little embittered at their own antics a few years back, they feared the man’s revenge would entice them with good victuals and gorgeous trappings and then leave them stupefied all over again, full guests feeling unaccountably foolish.

Some, chiefly the younger drinkers, laughed at the greybeards and said this was likely to be a different story. Even if this new stone signalled another rock garden, they said, most likely the stones would be borrowed from elsewhere and not from that now vanished pile no longer heaped in an unused patch. Certainly, this new stone looked homely and kindly in comparison with the great, grand, unbelievably ancient-looking tower of a stone that had stood at the entrance to the old rock garden. Yet there was no denying the general concern that a new garden party would generate some unexpected disturbance; for though the man was not known for doing very much, strange rumours circulated about his friends. And so, while the design of the new rock garden was clouded by impenetrable fog, a shadow of fear fell upon the hearts of the company at the prospect of new mischief in the garden, some magic that they guessed was already brewing in the house. Around the end of February 1938, with a collective resolve to discover the man’s designs before it was too late, the Fellowship was formed, with Boffin as its president.

Inevitably, nothing happened for months. The man simply stopped working in his garden. Most days he got on his bicycle and headed into town. At this point there were only the two stones: the first, the party stone, where the initial mischief was expected, and one terrible central stone. Boffin had not been surprised to see this second stone erected. Indeed, his reputation at The Green Dragon went up considerably after it was, because all those who had seen the three terrible central stones of the old rock garden felt a tremor of recognition when they glimpsed this new central stone. This stone was larger and more foreboding than those three, yet bore a family resemblance to each. A progenitor, it was whispered in the public house.

One freezing day in late February, when nobody in the house was likely to step outside and he knew that the rapidly falling snow would cover his tracks, Boffin had entered the garden and inspected the central stone at close quarters. You needed to know what you were looking for but, yes, worn markings traced the face of a monster long vanished from the face of the earth. The face appeared human, but the eyes stared out at you with a cold mythological hunger. Further inspection revealed strange twisted lumps of semi-precious amber embedded within this sinister stone, entombing winged carcasses from a primordial age of the world, trapped and held for time out of mind in the fossilized sap of some prehistoric northern tree. Boffin had drunk no beer but only spirits that night.

Alarmed by Boffin’s report, the fellowship tried various tricks to gain entrance to the house, where it was generally agreed the design of this new rock garden was being mapped out. They recruited a neighbour and his wife to the conspiracy, and before he was unmasked the neighbour many times disturbed the man at his work, asking a favour while spying out his study. This neighbour told the friends a strange story of an enormous canvas and a vast painting, of which he could recall agonizingly few details. After some while, though, he stopped coming to The Green Dragon and rumour had it that he had hung up his hat and entered the picture. But Boffin and his friends argued that a picture was not so different to a rock garden, of which they had already dug up one, and what they really wanted was the man’s design, which they reckoned was kept in one of the drawers of his desk.

One idea that sounded feasible was to impersonate an Elf-friend. It was generally agreed that the man’s door was open to them. But nobody was too sure what an Elf-friend was. Some said that the man’s best friend had been one, while today some say also his youngest son. Likely some of his acquaintances back then were too. Yet none dared recruit any of the man’s close friends to the conspiracy, let alone his children, and all who took it upon themselves to impersonate Elf-friends were given good morning at the door and sent on their way.

So the friends had to settle for Boffin’s walk-by garden-observation approach, which they now performed in pairs. And though for some weary months the walker-watchers reported nothing, all of a sudden one day in the late summer their efforts were rewarded: the man stepped out into his garden with an oddly coloured third stone. The watchers reported a shifting of the soil before this stone was laid, placed most carefully at once up-down and under-hill, so bringing into view what had always been there. The report started the strange rumour that this third stone was ‘uncreated,’ and to some it now seemed clear that a nonsensical spell of absolute power was the source of all the magic. So, for a little while, tongues talked only of this singular third stone.

But soon after the laying of the third stone, in the autumn of 1938, as the leaves fell and the wind began to nip, the man raised a conical mound of earth so that the top seemed to touch the stormy weather, planted a small flower near to the top, and then pierced it with a dark splinter from the monstrous central stone. All talk of the third unmovable stone immediately ceased, for it was agreed by all that it had no bearing whatsoever on the terrible injury to the flower. Everyone was most concerned, and Boffin became obsessed with discovering the terrifying mystery of the new rock garden.

Unfortunately, there is not much more to be told of Boffin. For a while he and his friends kept a keen watch on the garden, but as the days went by his friends began to keep their wary eye on him. In the new year the man stopped working in his garden and in March he left his house to travel north beyond the border. Over these short days of the year, when the nights are cold and long, the friends at The Green Dragon gradually lost interest in the rock garden—all but Boffin, who talked endlessly of the flowers and their relationship to the stones, till the other regulars begun to shuffle in their seats and his friends avoided his table. The walks continued, yet seemed increasingly futile. Untouched, the rock garden remained the same day after day. Nor did anything change in the garden on that fateful day in March 1939, when Boffin was accompanied on the daily walk by the friend whom we do not name.

When they arrived at the house the rock garden was, as both knew it would be, just as it had been the day before—and every day so far of 1939. The man had done nothing since the new year. Forlornly, the pair stood out in the street looking through the drizzle and over the gate and into the study, where a window had been unaccountably left open. Then, out of nowhere, a flash of blue light disorientated them both. Opening their eyes, they perceived a stone now on the table, through the open window on the other side of the rock garden beyond the garden gate. Boffin was opening the gate as his friend was frozen to the spot. Strolling past the stones he reached the window, and now it was he who was rooted to the ground. The drizzle turned to rain and the friend remained outside the gate wishing for a drink by the fire. But Boffin would not leave the eaves. Only that evening did the other friends learn that Boffin had been left alone inside the garden by an open window! Some better friends hastened to the man’s house, only to arrive moments too late. An odd blue light shone within the study, they said, and, as they reached the gate, they saw Boffin stepping through the window. With open mouths they watched him enter the room and pick up the stone, which now shone with no colour at all. He held it up to his face and for a moment a burglar was caught by a stone. There was no flash, not even a sound, as Boffin and the stone both vanished.

Boffin’s disappearance was more than a nine-day wonder. A search over the whole of Oxfordshire and even the Berkshire Downs failed to find any trace of him. Then out of the blue, one day in late summer 1940, Boffin inexplicably reappeared. But he was changed, almost beyond recognition. He now wore wooden shoes and it was said that something nasty had happened to his feet. But he never explained—indeed, he never talked at all about his adventure between his mysterious vanishing and unaccountable reappearance. Grim of face, he stepped again into The Green Dragon only on that stormy night when he surrendered the stone and resigned his part in our Fellowship. To this day he keeps to himself. Most days he is to be seen working his own garden—building little rock gardens of his own, each of which lasts for a while, an hour or a day or a month, until the stones are piled once again in a heap and, after carefully tending to the flowers, which remain rooted in the ground, a new pattern is begun. We who keep his stone unused do not forget Peregrin Boffin, our absent friend.

On the rumours of a new rock garden

Typewritten A4 page from the same archive folder as the story of the friend, also unsigned (probable date: mid-1970s)

Poor Boffin. He walked twice into the same trap yet never saw his shadow. His friends hailed a martyr to scholarship, eulogizing a noble seeker of truth and fudging the burglary. Naturally, Boffin handed over the stone as soon as he could, not wishing to be caught a third time by a snare for inquisitive friends. His only condition was that the Fellowship, from which he formally resigned, conceal the Stone from the eyes of the innocent and keep it out of the hands of the foolish.

We must repeat once more the warning that has always been communicated to the general public: Boffin’s stone is not like the enchanted stones of the new rock garden. A reality checkpoint, the Boffin Stone shows only the rock garden, gifting a vision of what it is. Those who look into this stone discover themselves back in the old rock garden as once it was, a work of scholarship resting on Elvish art. Few recover from this vision.

Today in a location safe and secure, the stone that Boffin took into his own hands on that fateful day in March 1939 is kept under lock and key. In the balmy days after the Six-Year War, when the new rock garden was first unveiled, it was generally assumed that the Boffin Stone would soon join the new rock garden on public display. The coronation of the young queen heralded a brave postcolonial dawn; but in 1956 the confidence of our nation of settlers again collapsed, and the rising generation has been raised on the pure fantasy of the Cold War. The man who made the new rock garden has many new Elizabethan friends, but very few have ever expressed a wish to look in Boffin’s stone. As guardians of the Boffin Stone, the Unimaginative Friends encourage this public reticence, circulating on occasion new stories of foolish friends who have been caught by the stone.

Acknowledgements

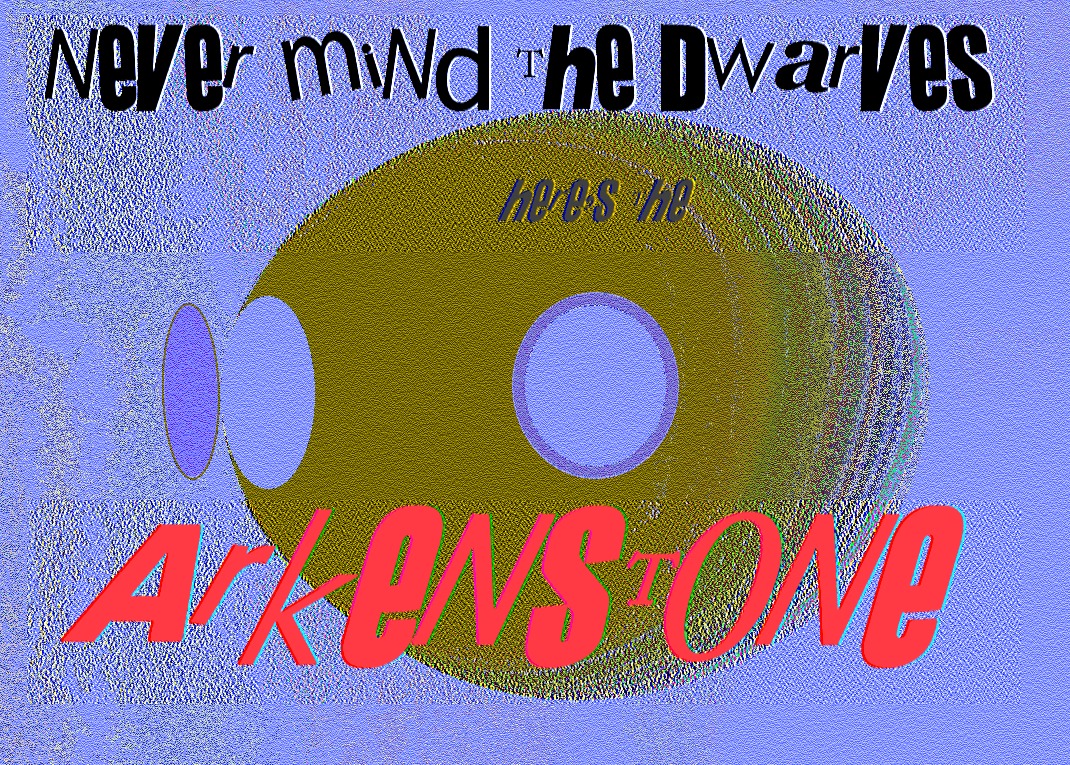

The story was originally entered in a short story competition on The Lord of the Rings Fanatics Plaza, where it came second (out of two entries). Nevertheless, it is my pleasure to acknowledge the literary craft displayed here, as in everything they write, by the author of the winning entry, who was then known as Frost. The image, however, won first prize in a Plaza art competition, which I find inexplicable. The drawing is inspired by a Sex Pistols album cover. On the original image, see here.

I was very entertained by…

I was very entertained by how you mixed Tolkienesque styles and motifs here into a kind of allegory of academia and interpretation. The concept reminds me of the Notion Club Papers, although I admit don't know those particularly well.

I am intrigued but puzzled how vital you hint here the aspect of the Tower parable is that you believe has been missed. I believe you have not revealed yet what you think the right reading is? Although I could have easily have missed clues. I have not been able to follow all parts of the series with equal attention.

Himring, two months after…

Himring, two months after you posted this comment I am only now lifting my head up again. Due to personal circumstances I was at a complete dead-end when I read your comment, and was considering calling a halt to the series. But you pointed me directly to 'The Peaks of Taniquetil', the January post, where I suggest approaching the allegory of the tower from the point of view of similar towers in other stories. By rights we should now be on 'The Fall of Númenor', but while I think this text is where the gold is buried, I also find it extremely difficult, and so opted to tackle 'The Lord of the Rings' first.

But when it all comes round again, what I hope will be clear is that the view on the sea has to do with both Fairy and History - at once a realm of imagined enchantment and an age of enchantment that is now vanished. So when turned back round to face the consensus reading of the 1936 allegory today, my bottom line is that we have received the notion of Fairy but lost any sense of History.

On the story itself, I wrote it a few years back (my very first story). And it seemed to fit the series (and saved me from writing a post). But after it was published I noticed that it spectacularly fails to fit. At the time of writing I was already engaged with the metaphor of the rock garden, which Tolkien uses for Beowulf and I wanted to apply to The Lord of the Rings. But I was not yet thinking about the Elf-tower to the west of the Shire, which I now deem the center of things. So as the man lays down the new rock garden, he fails to put down the one stone that actually matters to this series!