Grief, Grieving, and Permission to Mourn in the "Quenta Silmarillion" by Dawn Walls-Thumma

Posted on 15 April 2024; updated on 15 April 2024

This article was presented at the Tolkien at UVM Conference on 13 April 2024.

Grief, Grieving, and Permission to Mourn in the "Quenta Silmarillion"

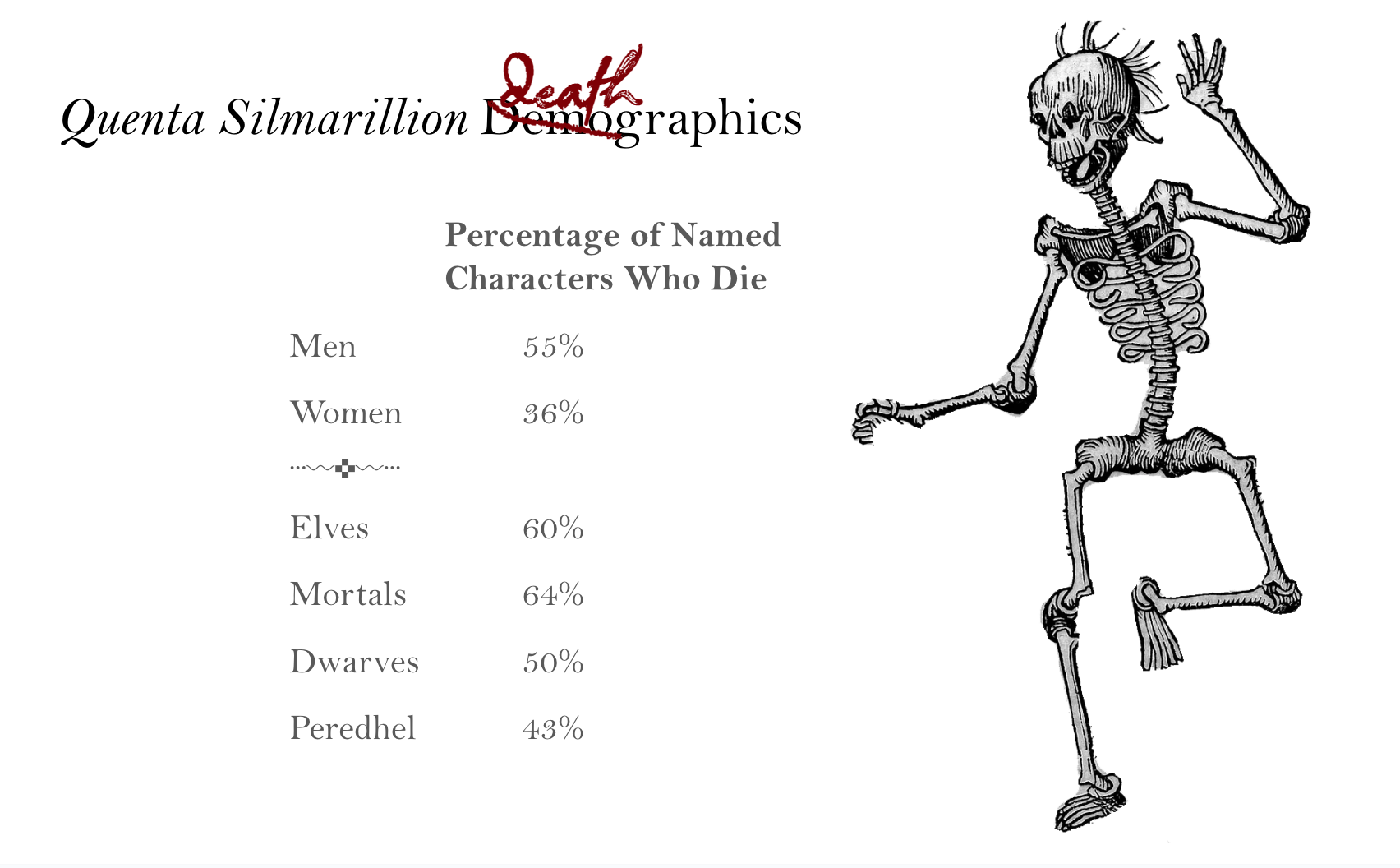

Few jobs are as dangerous in Middle-earth as simply existing during the First Age while in possession of a name. Just over half of named characters in the Quenta Silmarillion, the third "book" of the published Silmarillion and the longest, die in its pages. That's eighty-eight named characters who die ninety deaths in a text that is just over 100,000 words long.

Grief is one of the universal experiences of the human psyche, something all of us endure and an experience so profound that, through grief, we recognize a connection with people otherwise unlike us. Given the graveyard that is the Quenta Silmarillion, it is a text ideal for analyzing how grief manifests in Middle-earth.

In the Quenta Silmarillion, this analysis is complicated by the point of view from which the text was written. Tolkien crafted his stories as in-universe histories written by in-universe narrators who, like all of us, possess their own backgrounds, limitations, biases, and agendas. The Quenta Silmarillion, therefore, is not to be understood as history told from an uninvolved, omniscient point of view. Instead, it was "written" by a character or characters who lived at the time of the events described and knew at least some of the people about whom they were writing. The existence of a narrator of the Quenta Silmarillion is sometimes obscured by Christopher Tolkien's editorial choices in how to present the text: He removed attributions to the narrators, present through decades of drafts of his father's work, from the published text.

I have presented here before on my theory about the narrators of The Silmarillion1 and will just briefly review those ideas because they have significant bearing on how grief is presented in the Quenta Silmarillion. In short, reviewing Tolkien's drafts of the "Silmarillion" materials reveal two narrators for the Quenta Silmarillion: Rúmil, a Noldorin Elf of Tirion whose alphabet was improved by Fëanor into the Tengwar, and Pengolodh, a Noldorin-Sindarin Elf born in Beleriand who spent most of the First Age as Turgon's loremaster in the hidden city of Gondolin. Rúmil pens the Aman portions of the Quenta before Pengolodh picks up his work in the First Age and writes the Beleriand materials.

In 1958, late in his work on the "Silmarillion," Tolkien expressed in two notes a desire to shift from an Elven to a Númenórean narrator for The Silmarillion.2 This is why, in the published text, Christopher Tolkien avoided the question entirely by striking any mention of the narrator. As I've reviewed Tolkien's late "Silmarillion" writings, however, while Pengolodh's name disappears as an attribution,3 his perspective remains, and Tolkien never undertook the profound revisions needed to shift the point of view to Númenórean. Given that, I take Pengolodh as the narrator of much of the Quenta Silmarillion.

Pengolodh is an interesting choice as a narrator. Sequestered in Gondolin, he missed most of the tumultuous First Age history he was writing about. In the 1959-1960 text Quendi and Eldar, Tolkien explains that Pengolodh learned much about languages after the fall of Gondolin, from the refugees living at the Mouths of Sirion, and spent time in Khazad-dûm in the Second Age.4 His sources of information, therefore, are limited. Furthermore, Turgon, the king of Gondolin, was not apolitical. To the contrary, Turgon appeared to harbor strong feelings, both positive and negative, toward other characters and groups in the First Age, and one must wonder to what extent these biases influenced Pengolodh. As I hope to show, the depiction of grief—which should be a plentiful emotion in a text as deadly as the Quenta Silmarillion—and the expression of mourning are used by the narrator, Pengolodh, to humanize and dehumanize characters or to mitigate or castigate their choices.

Let's begin by considering the demographics of death in the Quenta Silmarillion—in other words, the raw textual material we are working with in considering grief and mourning in that text. In compiling these data, I first reread the Quenta, noted each time a named character died, and recorded the character's gender and ethnic or other group. These data show that it's risky business to be a named character in the Quenta Silmarillion, no matter who you are. Women are the safest demographic, though more than one in three named women die, and it's slightly safer to be a Peredhel than a Mortal, Elf, or Dwarf—but certainly not safe by any stretch of the imagination.

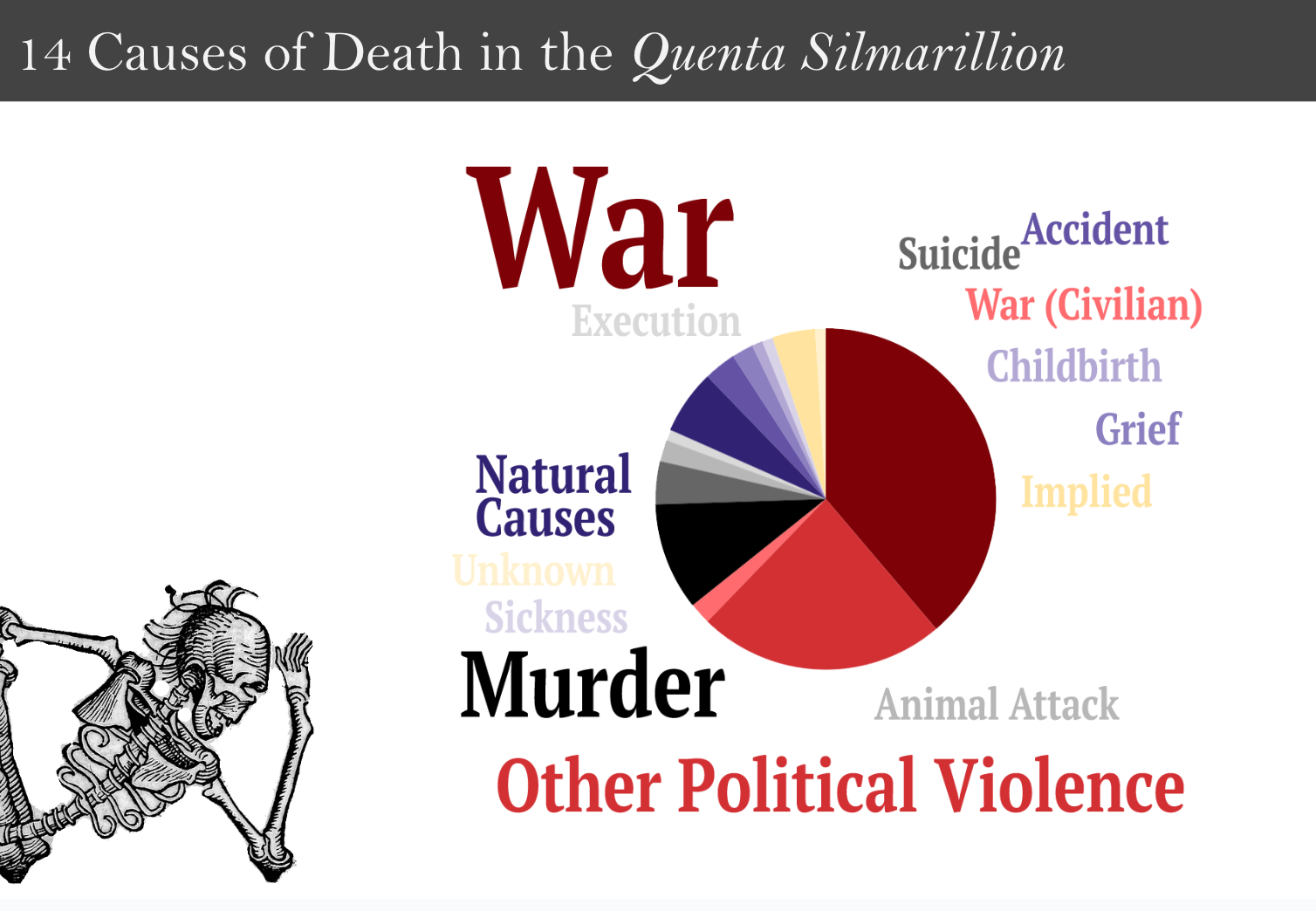

Cause of death proved much trickier data to collect. Back in 2015, I compiled a very similar set of data just to noodle around with on a Friday afternoon, and if I learned anything from posting my rudimentary results, it is that people felt strongly about how causes of death were classified for various characters. This time, being a little less noodly and a little more serious in my approach, I asked on the Silmarillion Writers' Guild's Discord server for volunteers to help me validate the data. Seven intrepid and much-appreciated people volunteered, reviewed the ninety death scenes I'd collected, and classified them as one of the fourteen causes of death listed on the screen.

The first big takeaway here is that cause of death in the Quenta Silmarillion is not straightforward. I included free-response fields on the validation form, and my validators often used these to vent frustrations along the lines of "This is really hard!" Despite the difficulty of the task, we managed to reach agreement for almost half of the death scenes, and only 17% ended up classified as moderate or major disagreement, with Finrod Felagund's death the only one where there was no majority agreement on cause of death. If you enjoy methodology and the finer points of cause-of-death definitions—or "deathinitions"—my website has all the details.

The second big takeaway is that war and other forms of political violence are by far the most significant cause of death in the Quenta Silmarillion. 72% of death scenes include some element of political violence, and 40% occur during war. Despite the surprise of Finrod's people at Bëor's death of old age, Bëor is an outlier—Mortals almost never get to grow old and die. Among ethnic and other character groups, there is little difference, and war is a major cause of death for everyone. Cause of death shows demographic differences between men and women: Not a single woman dies while participating actively in war or the other various outbreaks of political violence (though two do die as civilians), and no men die of grief. Death in the Quenta Silmarillion is gendered, therefore: Men die while in active participation and women are victims—of grief, of political violence, of murder.

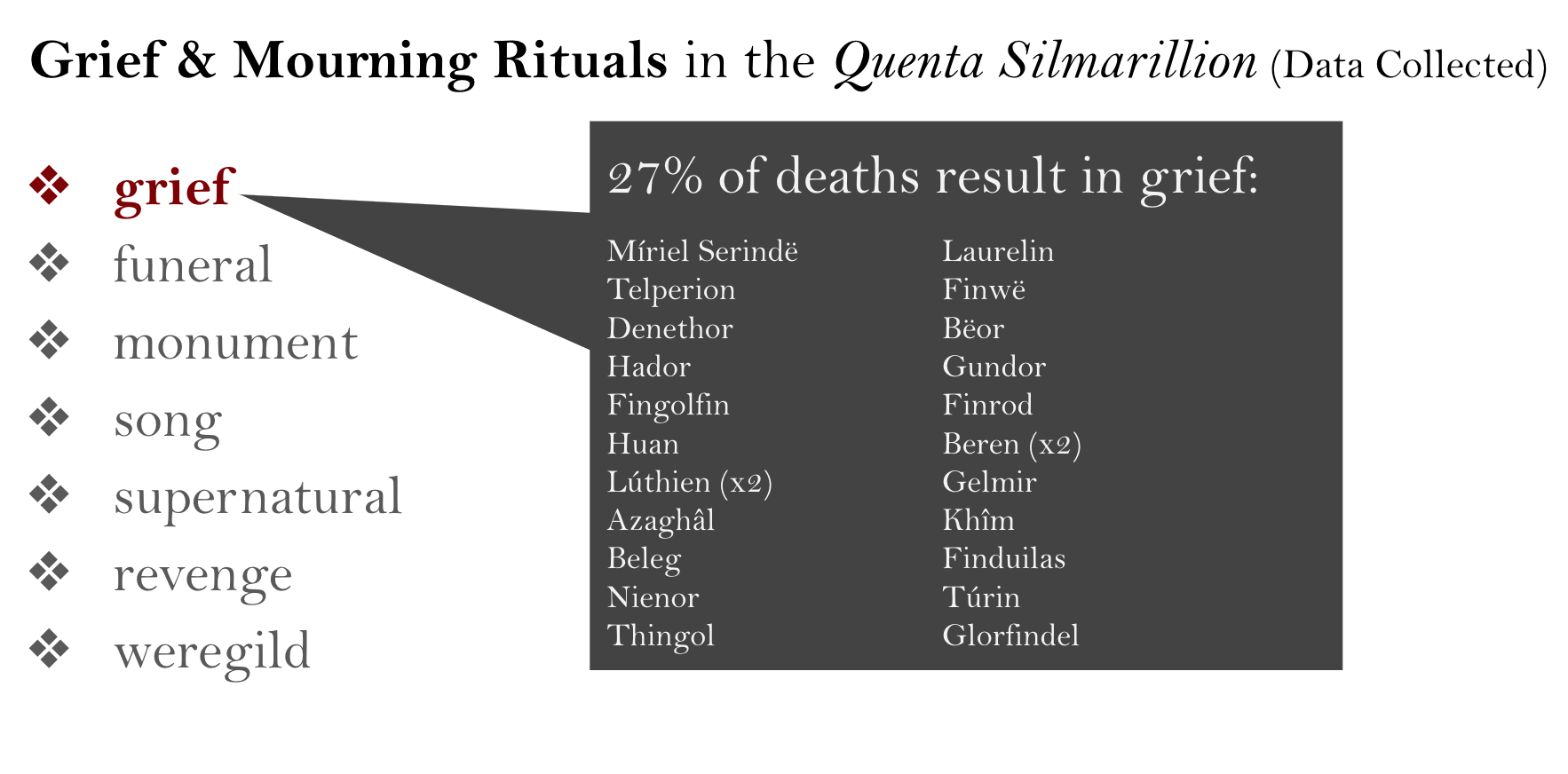

While reviewing those ninety death scenes, I also collected data on grief and mourning, and this is where the data get interesting and where we return to the influence of our old friend Pengolodh. Here, it is useful, too, to speak briefly on what has already been written on death and grief in Tolkien. I was surprised at how little I could find, and most of that focused on The Lord of the Rings, which is practically a wasteland compared to the lush orchard of death scenes found in the Quenta Silmarillion. Amy Amendt-Raduege in her 2019 book The Sweet and the Bitter: Death and Dying in J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings analyzes its death scenes using the medieval literary concept of ars moriendi—the art of dying well.5 In The Silmarillion, the narrator's attention to the grief and rituals of mourning that attend a death help construct "good" and "bad" deaths in the Quenta Silmarillion.

First, consider grief—namely, who among the dead is permitted to receive grief. Grief is humanizing—it reminds us of a person's humanity, beyond their deeds that we might harshly judge, as someone who was loved, cherished, and will be missed. Twenty-four characters in the Quenta Silmarillion—just over a quarter—receive grief in the aftermaths of their deaths. Who is included in this quarter is interesting. The list is shown on the screen.

First, given that there are sixty-four named Mortal characters in the Quenta, there is a dearth of Mortals who are grieved after their deaths—just six people. In all cases, grieved Mortals had significant connections with the Eldar. This offers a distinctly Elven perspective and is possibly in response to the ephemerality of Mortal characters. Death scenes for Mortals are among some of the shortest in the book and are annalistic and perfunctory in style: precisely how an immortal Elf might account for the death of a person who, to him, is but one name among many stacked high in a genealogy that functions mostly to document the ancestry of Mortals important to the Elves.

Several Elven characters are conspicuously absent from the list. Not a single Fëanorian appears, though this is unsurprising given Pengolodh's role as Turgon's loremaster. Turgon blamed the Fëanorians for his wife Elenwë's death and nurtured unwavering enmity towards them.6 Fëanor's death scene, in particular, shows how Pengolodh withholds acknowledgment of grief as a means to dehumanize certain characters, shifting the emphasis from their status as people to their deeds in the historical record.

Amy Amendt-Raduege identifies in medieval literature several hallmarks of a heroic scene or a "good" death. The character first pursues an enemy out of duty to the protection of his people or a desire to be remembered, even though he knows that defeat is likely. The death occurs in battle, against an insurmountable foe or odds. Mortally wounded, the hero is surrounded by his friends and gives a final speech before slipping from this world, knowing he will be remembered and mourned.7

Fëanor's death scene,8 which is one of the longest in the book, includes several of these traits. He pursues Melkor's host—though he is motivated by overconfidence and a desire to outfox the Valar. (How Pengolodh could know that, given that he wasn't even born yet, is open to conjecture.) Although destroying Melkor would offer protection not just to Fëanor's people but to the actual entire world, this is not allowed to him as a motive. In keeping with the formula, he is granted a final speech, but that speech is the opposite of uplifting. In the chapters set in Aman, Rúmil attributes Fëanor's actions to his unspeakable grief at losing Finwë.9 Pengolodh makes no such concessions, and Fëanor's final speech includes no mention of Finwë but urges pursuit of the Silmarils.

The most dramatic deviation from the medieval formula, however, occurs in the reaction—or lack of reaction—from his sons. Fëanor's sons are still relatively new to death and battle, and they not only watch their father die before their eyes but combust and scatter as ash on the wind. This must have been a terrifying, traumatic experience, but Pengolodh's description of the seven sons' reaction is emotionally sterile—in fact, as their father died, they disappear entirely from the scene and are not even mentioned. The result of this is that Fëanor's status as a loved, grieved human being never mitigates his actions and final speech. As a historian, Pengolodh leans heavily on the Oath of the Fëanorians as an explanation for the history of the First Age. The centering of this final speech absent any grief from those at his side foregrounds Fëanor's culpability for the havoc his sons will wreak in the centuries to come.

Aredhel and her family go similarly ungrieved.10 While a lack of grief for Eöl and Maeglin is understandable—Pengolodh is unlikely to try to humanize the person responsible for Gondolin's fall—in Maeglin's case especially, he sees his mother murdered by his father and his father brutally executed. Within a space of hours, he becomes an orphan, partly at the hands of the state—and he is allowed no emotional reaction to any of that. In fact, his lack of reaction seems to precipitate Idril's mistrust of him. Like the Oath of the Fëanorians is used by Pengolodh to explain the course of history in the First Age, Maeglin's stoicism here is positioned so that it seems to predict what follows.

The lack of grief for Aredhel is more difficult to explain. She is Turgon's sister, and he put considerable effort into keeping her safe and was delighted at her return. That he orders the execution of Eöl after she dies shows the strength of Turgon's response: This is the only example of capital punishment among the Elves in any of Tolkien's works. But, at the same time, execution applies the cold rationality of law. There is no emotion in the scene. Turgon does not rant or grieve; the most that is said of him is that he "found no mercy." Even the execution itself occurs at one remove from Turgon, who does not carry out the sentence himself. Instead, it is an anonymized "they" who drag Eöl to the precipice and cast him over.

The effect this creates is similar to the lack of grief for Fëanor. Grief is the expected reaction, and when it does not occur, it centers the barbarousness of Eöl's act (and the coldness of Maeglin's reaction). We understand that Aredhel has brought this into Gondolin, the most geographically protected location in Beleriand. Taken with her restlessness, her defiance, her unconventional marriage, and her preference for her brother's enemies, the sons of Fëanor, we also understand Aredhel as morally corrupt and partly accountable for Gondolin's fall.

All of the characters I've discussed so far, with the exception of Aredhel's more complex case, would have been perceived as the political enemies of Gondolin. This is important. Pengolodh also writes about the deaths of people who would have been favored by either Turgon in Gondolin or his Doriathrim sources after Gondolin's fall. Fingolfin, Turgon's father, is the most notable example of this. Fingolfin has the longest and most lavishly written death scene in the Quenta Silmarillion.11 Like Fëanor's death scene, it relies on the medieval formula for a "good" heroic death, but here we see how Pengolodh emphasizes elements of this formula to evade questions around the ethics of Fingolfin's choices.

Fingolfin, who rides forth in a fit of wrath to single combat with Melkor after the terrible defeat of the Battle of Sudden Flame, essentially commits suicide-by-Dark-Lord. Amendt-Raduege points out that suicide, in the Middle Ages, was the bad death of bad deaths—an actual crime against God.12 Unlike the heroic death Amendt-Raduege describes, Fingolfin's desperate actions are not aimed at protecting his people—in fact, the opposite is true. He is motivated by wrath, just like Fëanor. Fingolfin's death leaves a power vacuum to be filled at a most inopportune time. Pengolodh, in writing about his death—of which there was no eyewitness save his horse and the Eagle Thorondor—is tasked with rescuing him from this bad death and restoring him to heroism.

Fingolfin's death invites us to consider not just grief but rituals around mourning. Multiple scholars have shown medieval analogues for the mourning rituals we see in The Lord of the Rings.13The Silmarillion is no different. People gather for funerals, construct monuments, and compose songs to memorialize the dead. As with grief, in the Quenta Silmarillion, these rituals are politicized by the narrator, Pengolodh. The characters who receive them are almost all characters who would have been favored by the communities Pengolodh belonged to at various points in his life: Gondolin, under Turgon's leadership; the Mouths of Sirion, with the refugees of Doriath; and Khazad-dûm.

Like grief, these rituals depict the deceased character as someone worthy of the love and regard of his or her people. However, they serve a more enduring function as well, especially monuments and songs, as we will see in the case of Fingolfin. In describing Fingolfin's battle with Melkor, Pengolodh chooses language that aligns him with the Valar and forces of good. However, the fact remains that Fingolfin rode off in a state of wrath, abandoning his people at perhaps their greatest time of need, to pursue combat that is at best foolhardy and at worst an act of vanity.

Two characters in the Quenta Silmarillion receive the platinum funeral package, including not just grief from their people but a funeral, monument, and a song about them: Glorfindel and Fingolfin. Just as their loved ones' silence cast doubt on the characters of Fëanor and Aredhel, the heaping up of funerary honors onto Fingolfin sends a clear message that his people see his act as worthy of commemoration. They do not see it as foolhardy, vain, and certainly not suicidal—a "bad" death. Even though it is missing some of the key elements of a hero's "good" death, his people construct permanent memorials that say otherwise.

Furthermore, Fingolfin receives honors beyond even golden Glorfindel. First, there is an element of revenge, as Thorondor arrives to attack Melkor and prevent further desecration of Fingolfin's corpse—a defense worthy of a hero-king. Then, there is a supernatural after-effect of Fingolfin's death: Melkor limps ever after, with scars upon his face, and "[n]o Orc dared ever after to pass over the mount of Fingolfin or draw nigh his tomb."14

Amendt-Raduege conceptualizes a "bad" medieval death as a failure.15 Through this lens, it is interesting to consider the death scenes so far discussed. With their deaths, Fëanor, Aredhel, Eöl, and Maeglin all failed. Fingolfin's death, likewise, should be a failure. Even with the honors bestowed by his people, a discerning reader should see that those people were left in the lurch—he failed. The supernatural effects attached to his cairn, however, negate that failure. Not only is Melkor left weakened, but Fingolfin's heroic awesomeness continues to repel the enemy from beyond the grave. He did not, in other words, fail. The excesses piled upon him by Pengolodh can be seen not just as flattery aimed at Turgon but as a counterweight to the moral and ethical questions that Fingolfin's death raise. Pengolodh does not hold back. Fingolfin, we are pressed to see, is a hero. No questions need be raised.

Three other characters elicit a supernatural after-effect around their deaths: Finrod Felagund, Morwen, and Elu Thingol. Like Fingolfin, both Finrod and Thingol's deaths could be seen as failures, as "bad" deaths. Finrod, much like Fingolfin, also abandoned his people. In his case, it was to fulfill an oath—and by this point, Pengolodh has hammered the point home with the Fëanorians that oaths cut swaths of destruction through a civilization. Pengolodh finds himself in a bind with Finrod—a political favorite who makes an ethically fraught and bad choice. Finrod is grieved and given a monument that cleansed the polluted isle of Tol Sirion, which then "remained inviolate" until Beleriand was flooded—an act precipitated by the Valar and therefore understood to be good. As with Fingolfin, the reported response of Finrod's people and the lingering restorative and protective effects of his grave classify him as a hero.16

Thingol's death is treated similarly. Killed in a greedy squabble with Dwarves over a Silmaril, Thingol cannot be seen as a hero, nor his death anything but a failure. Like the other two kings before him, his death is grieved, and while he is not given a monument to benevolently haunt unto the drowning of Beleriand, the Silmaril that he gave his life for is sent to Lúthien, and we are told "that immortal jewel was the vision of greatest beauty and glory that has ever been outside the realm of Valinor; and for a little while the Land of the Dead that Live became like a vision of the land of the Valar, and no place has been since so fair, so fruitful, or so filled with light."17 Again, through a supernatural after-effect from his death, a shameful death is reversed into a heroic one.

Historical texts exist to make permanent a particular perspective and ensure it is the version that is remembered. In The Silmarillion, Tolkien does not utilize point of view in the way we generally think of a novelist assuming a character's perspective. Instead, he expresses point of view in historical terms, as it existed in the texts he studied as a scholar of medieval language. Grief is a universal part of being a human, and when Tolkien allows his narrator to withhold grief from certain characters—or heap it onto others—it becomes an expression of the narrator's bias and point of view. On the other hand, characters who should be open to criticism are spared by the strength of their people's reactions to their deaths. In this way, Tolkien permits his narrator to keep the focus on aspects of the story like the Fëanorian Oath or Maeglin's treachery without allowing readers a glimpse of their humanity through grief or mourning.

An audio recording of this paper, the slideshow that accompanied it, and a fuller accounting of the methodology can be found on my website: Grief, Grieving, and Permission to Mourn in the Quenta Silmarillion.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to my data validators, who waded through a lot of death scenes, made some tricky decisions, were thoughtful and thorough, changed my mind when needed, and made this project better for their efforts! JazTheBard, Grundy, AdmirableMonster, Angamaitë, HelenFloraW, Chris Steinwascher, and Nelyafinwefeanorion.

Works Cited

- Dawn M. Walls-Thumma, "The Most Important Characters Never Named: Unveiling the Narrators of The Silmarillion" (paper, Tolkien at UVM Conference, Burlington, VT, April 6, 2019).

- The History of Middle-earth, Volume X: Morgoth's Ring, Myths Transformed, "Text I": "It is now clear to me that in any case the Mythology must actually be a 'Mannish' affair. … What we have in the Silmarillion etc. are traditions … handed on by Men …" (emphasis in the original) and, "The three Great Tales must be Númenórean, and derived from matter preserved in Gondor." Later, "Text VII, section iii" states: ""[The myths] have reached us (fragmentarily) only through relics of Númenórean (human) traditions, derived from the Eldar, in the earlier parts, though for later times supplemented by anthropocentric histories and tales." This latter text is harder to date than "Text I"; Christopher Tolkien estimates it to come from the late 1950s.

- We have a couple of examples that seem to show Tolkien, in the 1950s, experimenting with (and abandoning) the possibility of a Númenórean narrator. A typed version he made of the 1951-52 version of The Annals of Aman (called AAm* by Christopher Tolkien in Morgoth's Ring) attributes the text to the Númenóreans but otherwise includes no edits that suggest that point of view; the text was swiftly abandoned, and a 1958 typescript includes the typical attribution to Ælfwine. In his 1958 work on the text called The Later Quenta Silmarillion (or LQ2), also in Morgoth's Ring, we see Tolkien remove an attribution to Pengolodh that was present in the 1951-2 version of the text ("Of the Silmarils and the Unrest of the Noldor"), and Pengolodh (nor Ælfwine) are not attributed elsewhere in this later version of the text. Was this an early attempt to follow through with the intent to change to a Númenórean narrator? It certainly seems likely, given the same intention expressed in "Text I" of Myths Transformed in the preceding footnote. That the revisions were not carried further likewise suggests that the deep, significant effort this represented was never undertaken.

- The History of Middle-earth, Volume XI: The War of the Jewels, Quendi and Eldar, "Appendix D" (omitted section).

- Amy Amendt-Raduege, The Sweet and the Bitter: Death and Dying in J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings (Kent State University Press, Kent, OH, 2017), 10.

- The History of Middle-earth, Volume XII: The Peoples of Middle-earth, The Shibboleth of Fëanor, "The names of Finwë's descendents."

- Amy Amendt-Raduege, The Sweet and the Bitter, 10-11.

- The Silmarillion, "Of the Return of the Noldor."

- The Silmarillion, "Of the Flight of the Noldor": "... for his father was dearer to him [Fëanor] than the Light of Valinor or the peerless works of his hands; and who among sons, of Elves or of Men, have held their fathers of greater worth?"

- The Silmarillion, "Of Maeglin."

- The Silmarillion, "Of the Ruin of Beleriand and the Fall of Fingolfin."

- Amendt-Raduege, The Sweet and the Bitter, 32.

- Reynolds, Patricia. "Funeral Customs in Tolkien's Fiction." Mythlore 19.2 (1993): 45-53, and Amendt-Raduege, The Sweet and the Bitter.

- The Silmarillion, "Of the Ruin of Beleriand and the Fall of Fingolfin."

- Amendt-Raduege, The Sweet and the Bitter, 29.

- The Silmarillion, "Of Beren and Lúthien."

- The Silmarillion, "Of the Ruin of Doriath."

Fascinating, because....

....I completely bought into Pengolodh's bias that Fingolfin's death was epically heroic and worthy of praise (and a monument), forgetting about the ramifications of him going off in anger and frustration for single combat with Morgoth. I love how descrptive the phrase " suicide-by-Dark-Lord" is. He abandoned Fingon and left his warriors behind (an example of bad leadership?).

Oh, I totally bought it too!…

Oh, I totally bought it too! It wasn't until I picked out the parallels between his death scene and Feanor's that I began go, "Hey, waaaaait ..." And especially after reading Amy Amendt-Raduege's The Sweet and the Bitter and her conceptualizing so clearly the ideas of "good" and "bad" deaths in the European Middle Ages. Fingolfin's death checks a lot of the "bad death" checkboxes! He forsakes his people's safety to give in to "wrath." (This exact word is used in Feanor's death scene, which Pengolodh clearly disapproves of. But for Fingolfin ... it's all cool?) But even more than that, which I couldn't get into in my twenty minutes at Tolkien at UVM, he does so due to despair, which is one of the emotions also associated with a bad death, according to Amendt-Raduege. So it's not like he believed that he would strike an important symbolic gesture for his people by going after Morgoth. No, he thought, "Well. It's all fucked anyway, so I might as well give in to my baser emotions." Notably, Feano—while not guiltless, obviously—does not give in to despair and could even be read as acting in protection of his people: to secure all of the world in safety from Melkor once and for all. (Kind of the opposite of the Valar capturing Melkor and then not finishing the job at Utumno.)

What I find fascinating is that Tolkien allowed Pengolodh to be very honest about Fingolfin's shortcomings. So, at the risk of inferring Tolkien's intent, it seems he wanted us to see that. And then he cleverly builds up the grief/mourning afterward to negate—even upend—those failures. The whole scene, once I really picked it apart, is quite cleverly done, especially given that he uses the same structure later on for Finrod and Thingol's death scenes as well.